Recommendations for the coronavirus lockdown have been appearing on almost every newspaper book page. ‘What are you reading?’ ask friends, once they have enquired if one has adequate supplies of haricot beans, bread flour, yeast (unobtainable), loo rolls … gold-dust. Some are planning the great catchup: Proust, Pallisers, others are happy to admit to indulging in the reading equivalent of eating their own body weight in Maltesers, full works of Donna Leon. Our suggestion, of course, would be ‘any Persephone book’, adding perhaps, the longer the better. We need total immersion at the moment.

The Forum book for March 2020 happens by good fortune to be The Call, perfect. It is a terrific read, an absolute page-turner, which ticks all boxes – great plot, engaging characters, historical interest, domestic detail. And ‘Persephone Books’ seems watermarked on every page: I found myself half expecting other Persephone characters to walk in to a picnic, a party, a suffragette meeting or a WW1 convalescent hospital: Delia and Muriel (The Crowded Street PB 76)) making the case for women’s education and independence, Wilfred and Eileen (Wilfred and Eileen PB 107) sharing the agony of love in wartime, Alice Walker and Mary O’Neil (aka Constance Lytton) exemplifying the courage of the suffragettes (No Surrender PB 94).

The Call opens in 1908, the year in which Constance Maud, author of No Surrender, joined the Women’s Social and Political Union, the militant breakaway suffragette movement led by Christabel and Emmeline Pankhurst, and closes as the War nears its end: turbulent years, politically, militarily and socially, years in which minds were changed, the positions of men and women challenged, and the class structure re-evaluated. Edith Ayrton Zangwill’s and her stepmother had joined the WSPU the previous year.

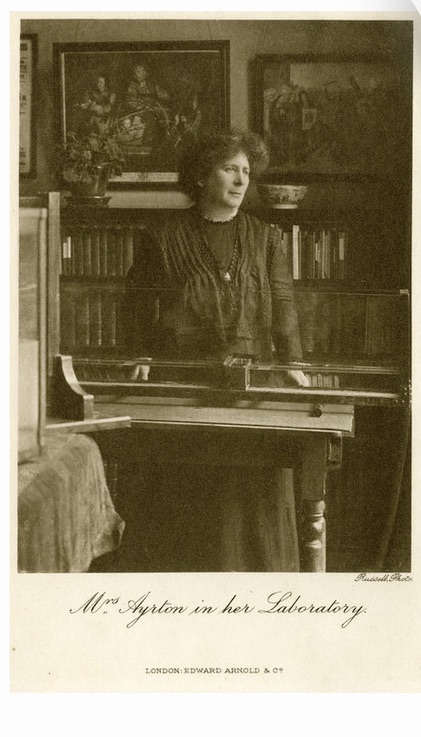

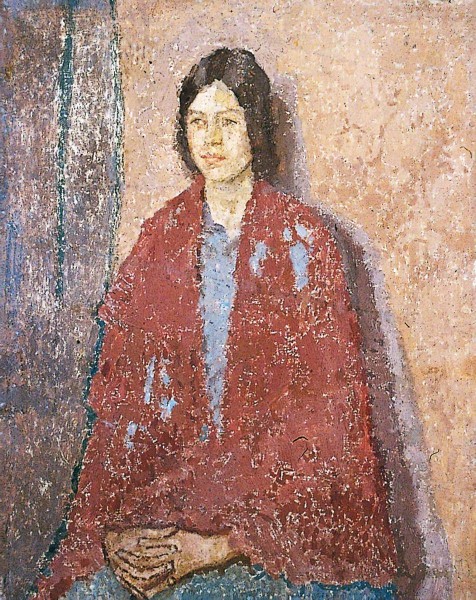

The Ayrtons were no ordinary family. Edith’s mother, who died when Edith was eight, practised as a doctor, having been awarded a degree by the University of Paris, medical courses in England and Scotland being barred to her (she was awarded a posthumous MBChB at the University of Edinburgh in July 2019). Her father, Wiliam Ayrton, an electrical engineer, was a committed supporter of the WSPU. Her stepmother, Hertha, was a physicist, friend of Marie Curie, and of George Eliot – Mirah Cohen in Daniel Deronda is based on Hertha. Neither Hertha, nor Edith, for health reasons, took part in militant action, but suffragettes who had gone on hunger strikes would often recuperate at the Ayrtons’ house.

Hertha was the model for Ursula Winfield, the novel’s heroine, and what a heroine! We meet her only after having been given a tour of the family’s fashionable Knightsbridge house , ‘the sort of house that inspired trust in tradespeople and caused the socialists to fulminate’, a house with handsomely proportioned rooms, well filled with handsome furniture, boasting, as the property agents would say, a library, in which there were hardly any books, a study, with a large writing table, ‘again a figure of speech, for the gallant colonel [our heroine’s step-father] never wrote anything but cheques’. This is not an intellectual family. Our heroine’s mother, who favours pink chiffon and ninon for her wardrobe, has furnished her large drawing room with ‘so-called Louis Seize’ furniture, while her boudoir is scattered with Dresden figurines, and photographs, ‘chiefly of good-looking young men’. Edith Zangwill doesn’t pull her punches.

How surprising, when we follow Mrs Hibbert up the stairs to the top of the house, past the servants’ (many servants) bedrooms, to find a young woman in a shapeless blue overall, and dark goggles leaning over a laboratory bench. Even more surprising is the young woman’s greeting: ‘What has brought you up, Mummy?’ ‘Mummy’, ‘Mum’, ‘Mammykin’: the relationship is warm: ‘hardly of a filial character’, writes Zangwill, but both real and deep. Mrs Hibbert’s perfectly manicured pink nails, and her tiny shoes with Louis Seize heels and gold buckles (to match her drawing room?) belie more sense than such fluffy prettiness suggests.

Disappointed that her daughter has refused even to be presented, that she refuses to ‘go anywhere’ – not quite true: she has been seen and admired in Society – Mrs Hibbert nevertheless feels none of the desperation of other Persephone mothers fearing for the prospects of daughters unmarried after three ‘seasons’. Mrs Hibbert has been left a rich woman by her late husband, Ursula’s father. Ursula has an income of her own, £400 a year, and though her mother may hold fiercely conventional views on how a young woman of her class should behave in society, she has not been negligent about her education, nor, apparently, has she allowed her daughter’s even more conventional military step-father to intervene. After governesses, and a brief period at school, Ursula has been allowed, most unusually, to go to Bedford College, the first higher education college for women in the United Kingdom, perhaps even encouraged, in spite of the fact that her mother considers the other students ‘impossible’ (Mrs H’s word for anyone of the wrong class). The Call is Ursula’s story, but the slow reveal of her mother’s strength is woven into it.

Ursula is her own woman, a woman in a man’s world. In her early twenties, she is a regular attender at the august Chemical Society, a lone woman: ‘the Fellows had got used to her presence and, with some exceptions, rather liked it’, but Ursula could not aspire to be a Fellow herself. Women Fellows ‘would reduce its meetings to frivolous social functions’: the President was ‘genuinely unconscious of any sex hostility that lay behind his argument’, adds Zangwill, with a perceptible shrug of the shoulders. The chivalrous soft underbelly of sexism. Ursula is not raring for a fight. When her paper is announced as being by a Mr Winfield, she is amused rather than upset that it should be attributed to a man.

While she might welcome equal opportunity, the ‘woman question’ comes a distant second to her scientific work in importance. She attends the Society meetings under the auspices of her Professor, mentor, and inappropriate admirer. Professor Smee is something of a champion of women’s rights, excluding any right his plain, sad wife might have to faithfulness on the part of her husband. When he enquires of Ursula whether she is a suffragist, she replies that she is not Anti, but doesn’t consider it important, adding, ‘I am quite decided about the suffragettes. I utterly and entirely disapprove of them …. These “militants” make themselves so ridiculous.’

But Ursula is about to hear ‘the Call’, no more than a whisper at first. The Society meeting is the first of a series of vivid, perfectly constructed scenes, marking the stages of her journey from minimal interest and outright disapproval, to total commitment to the cause and horrific spells in Holloway.

A glorious light-hearted day at the Henley Regatta proves life changing. Her mother has lined up some eligible young men, one ‘a positive Adonis’, Anthony Belestier, out of the right drawer and a Balliol scholar, ‘but you would never think he was clever’ adds her mother, ‘he is too handsome!’ Ursula finds his well-cut features pleasant, and his figure admirable, no more. He fears that she will expect him to talk seriously, ’as though he didn’t get all the serious talk he wanted with other men.’ Tony Balastier is a young man of his times. But his conviction that ‘intellect in women was a mistake’, and Ursula’s avowed lack of interest in marriage, are far from rock-solid. The threads of a complex love story have begun to weave their way into the novel. The political and the personal will become inextricable, and conflicted.

As the Hibbert party picnic on the bank, the sight of a group of suffragettes on the river awakens in Ursula a glimmer of curiosity. She is surprised that they should be so good-looking and ladylike – ‘quite indistinguishable from other girls in other boats. Was it possible that these were the raging viragos of whom the papers were full?’ Determined to find out ‘why these girls demeaned themselves by doing these horrible things,’ she heads to observe a gathering in Parliament Square (we would now call it a demonstration), all the while protesting that she is not one of them. It is not what the women do but what the police do that shocks her.

Accounts of police brutality at the time are familiar enough, but I was shocked, though I suppose not surprised, by the description of a human chain of young men laughing and singing as they charge about in the crowd (am I alone in not having heard of this?), and then charmed by the constable regretting his actions and shielding what he thinks to be a baby in the arms of a woman he has mistreated; all the more charmed when the ‘baby’ turns out to be a brown paper package containing a newly bought and treasured blouse, ‘pink silk with them new glass buttings … and reel lace’, its owner no more a signed-up suffragette than Ursula at that point. But curiosity turns to anger and, eventually, much later, to solidarity, action and prison.

Zangwill’s detail is wonderful, sometimes quirkily funny. Mrs Hibbert writes after Ursula’s first spell in prison, enquiring as to whether she had remembered to take her manicure set to prison, ‘you have such nice nails: it would break my heart if you spoilt them picking oakum. By the way what is oakum? Can you eat it when it’s picked?’ Fully engaged in Suffragette action, Ursula is sent on speaking tours, where she is encouraged to accept local hospitality: ‘often her hosts were well-to-do business folk, only differing from the rest of their class in a passion for “causes” …. Vegetarianism, anti-vivisection, anti-vaccination … almost invariable co-existed with a suffrage sympathy.’ Offered in one such house a chopped apple and a Brazil nut, she risks asking if there might not be other food, perhaps for the servants? ‘At last a small boiled egg and a slice of bread and butter appeared. This I consumed under the reproachful gaze of seven infant nut-eaters …’

Some details are so specific that we hardly question that she is writing from her own experience: the unbearable never-ending chatter of the police waiting room such that Ursula longs for the quiet of a cell; the cardboard armour worn by the woman under their clothes to protect themselves; empty seats in the Albert Hall belonging to life holders released for other political meetings but not to suffragettes. Passive aggression on the part of the public.

Some, like Ursula’s brief respite from force feeding when a broken tooth makes it impossible to prise open her mouth, are unbelievably grim. Zangwill does not spare her reader, but she is never hectoring, deftly changing the tone and the mood, before revealing each new horror.

Nearly a hundred years on, the jury is still out as to how far the Suffragette movement helped win the vote. The lives of the women involved were changed without doubt, and the opinions of many of their husbands, fiancés, and brothers, though perhaps not their fathers. Ursula Winfield’s life was changed. A lonely scientist, ‘self-isolating’ in her laboratory, she emerges into the light to form new friendships, to develop into a confident speaker, an active champion of the rights of women, not only voting rights, but simple human rights. Her eyes have been opened. The Cause may have damaged her health but it has revealed untapped strengths.

Zangwill does not forget the women, who cared nothing for the vote, but whose strength would be needed in another cause. Mrs Hibbert and Mrs Smee stand for them. The fluffy upper-class socialite had been so relieved in 1910 that the King should have died when she chanced to be in Paris, perfect for elegant mourning clothes. Four years later she changes out of her habitual chiffon into a tailor-made suit, removes the Dresden china in her boudoir to make room for khaki knitting, and sets out each morning to help in a war canteen. Mrs Smee, who has always secretly preferred to be without servants, enjoying domestic chores, finding an ‘artist’s pleasure’ in cooking, is in her element running the canteen. Her husband, at last, respects her, and all the smart women, Mrs Hibbert reveals, are afraid of her. When the woman she had despised and disliked at first sight years before, ‘almost’ tells her that ‘she’s not such a fool as most of the others’, Ursula’s mother can hardly contain her delight.

Helped by a couple of serendipitous coincidences (but there are serendipitous coincidences in all our lives) the plot brilliantly entwines the several plotlines, giving every character (with the possible exception of the rather ghastly Colonel Hibbert) the chance to change and grow. Regardless of their flaws we love them all by the end.