Unlike the Persephone Post, or the Letter, the Forum, taking each book strictly in order of publication, seldom touches on current affairs. But this December 2019 we have been reading Tory Heaven or Thunder on the Right, a rare synchronicity that I like to think might have pleased its author, Marghanita Laski, a writer with politics quite literally in her DNA.

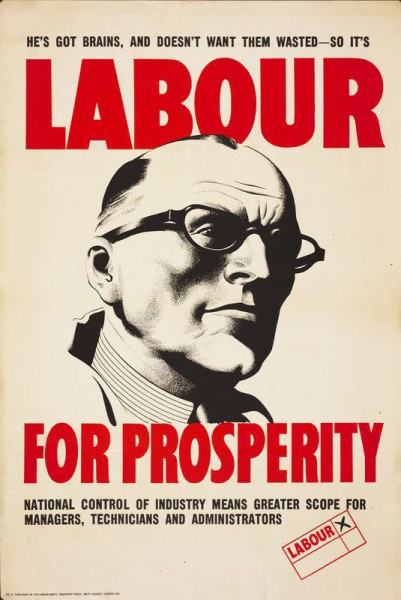

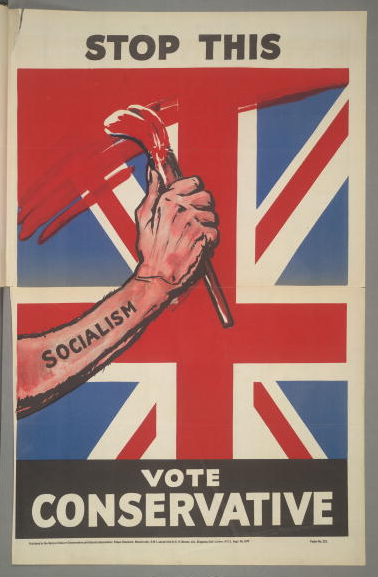

Her uncle, Harold Laski, the Labour Party Chairman, was among the principal speakers at Central Hall, Westminster, celebrating the astonishing result of the General Election on 26th July 1945, while his arch-enemy Beaverbrook, owner of the Daily Express, was condoling with his guests at Claridges, where a planned victory feast had unexpectedly turned into a wake. The result of our own recent election was not such a shock, but the size of the majority, though no match for Labour’s in 1945 – 80 compared to 146 – was definitely a surprise, the consequences of which we must await, with despondency, or enthusiasm, each to her own: Tory heaven, or thunder from the right. Persephone readers will know where we stand.

The Persephone catalogue suggests that some might find the novel too political, and others ‘both funny and disturbing’. The first time I read Tory Heaven, in 2018, I found it funny, and just a little disturbing. Re-reading it, I still find it funny, but a great deal more disturbing than I did two years ago, not because it is too political, but because aspects of the politics seem so immediate. How could Marghanita Laski have guessed?

Writing in 1947, she imagines a post-war England in which, having initially overwhelmingly endorsed a Labour programme of egalitarian rule, the public has become rapidly dissatisfied, and, given a second chance, voted even more overwhelmingly for a Tory government, ‘to do away with all that nasty equality bosh’, which had burgeoned during the war years of shared hardship and danger.

The country has reverted to traditional principles: the rich man is comfortably in his castle, the poor man firmly at the gate, and he is not alone there. Based on the belief that ‘people like to know where they are … and they like to know where other people are too’, the population has been formally divided into five classes (three more than Mrs Alexander had reckoned for in 1848 in writing the words to ‘All things bright and beautiful’), rated from A down to E, a classification reckoned by the Prime Minister to represent ‘the perfect flowering of the class system’. ‘Perfect’, but subtle, easy to get wrong, hard to navigate, with more snakes than ladders.

The innocent abroad, baffled by seemingly bizarre customs, and uncertain of the rules, is a familiar character in ‘politic0-philosophical’ fiction – Gulliver or Candide for example. The innocent returning from abroad to his or her own country after a prolonged absence, serves a similar purpose: exposing inherent absurdity to the light, Miss Ranskill is a perfect PB example (in Miss Ranskill Comes Home PB 46): ignorant of wartime regulations and rationing she assesses them with a cool eye, unintentionally but effectively challenging the logic behind them: why not for example use a week’s butter ration on one delicious piece of toast, or fill one blissfully deep bath, rather than seven mean basins.

In Tory Heaven Laski’s five characters, rescued from a lengthy Far Eastern island exile, return to a post-war Britain of which they have had only scant and inaccurate news, and which in any case holds little appeal for any of them. They have all had good reason to leave and little to go back to. A super-bright, zoologist, engaged in a government sponsored study of the effects of submarine blast on embryonic barnacle-geese (Laski doesn’t take her quintet too seriously), would prefer to pursue a new variety of Hippocampus discovered on the island. A ‘fishing fleet’ failure in her late twenties – no husband found in India, Egypt or China – is likely to be condemned to breed Angora rabbits on the family estate in Shropshire. A retired Passport Control officer, with (distant) aristocratic forbears and a mistress in Maida Vale, dreads life in London on a pension too meagre to stretch to more than a Bloomsbury bed-sitter. A rackety, beautiful blonde, whom we suspect of being no-better-than-she-ought-to-be, pins her hopes on Claridges being spared nationalisation. Our hero, nice but dim, has been sent to all corners of the world in the hope that he might find some area in which he might make some sort of a living, has tried, and failed in coffee, sheep, and rubber. This ex (minor) public-school boy can dance, ride and mix a cocktail, is good-looking, and has a hyphen to his name, but James Leigh-Smith faces a future selling vacuum cleaners door-to-door.

But the new class structure turns out to favour James, and the Passport Officer, Ughtred, and Penelope, the rabbit breeder. They will be As, and carry a gold disc by way of proof. A few simple questions suffice for James to qualify: did he play cricket? Had he any titled connections? What were the addresses of his nearest relatives? Had his mother been presented at Court? All boxes ticked, he won’t be selling carpet sweepers, but positively encouraged to follow his dream path. He is to be ‘a Man-About-Town’, given £3000 a year (in gold coins), and appointed to three directorships. Ughtred, on similar terms, is to be a ‘clubman’. Neither will be troubled by rationing but will enjoy an abundance of pre-war luxuries, only dreamt of by classes B,C,D and E. From soap, to foie gras, fine wines and cigars, James’s every wish is granted, up to an including a brand new old style Lagonda, ‘the sort with outside tubes and a strap round the bonnet.’

Not all A’s it emerges are idle and rich. The system is more nuanced than that. High ranking civil servants are admitted, as are Naval officers, and Army officers, depending on their regiment (all Air Force officers are B’s), and a limited number of University Dons. Birth is a given. Money helps, but does not suffice. Common to all A’s however is ‘an attitude of easy superiority’, a little phrase that would be less disturbing had we not heard so much recently of the defining Etonian ‘effortless superiority’. Ughtred, we learn, was James’s ‘idea of an educated English gentleman, which meant that he could discourse pleasantly on any decent subject without knowing enough to become boring about any of them’. Ughtred is no ‘girly swot’.

There is no place for girly swots, of either sex, in Tory Heaven: disapproved of in A men, it is forbidden for girls. There is to be no more university education for A girls, nor any work, other than charity work.

A’s are vastly outnumbered by B’s, who have silver discs and range from rich businessmen to small shopkeepers, with a tendency to congregate in suburbia or home-counties commuter-belt. ‘They may look like one big group to us [A’s]’ explains James’s father, ‘but inside themselves they’ve got literally thousands of different classes … they’re always much too busy keeping up their own little barriers inside themselves.’ It is incidentally this group, winners and losers in post war Britain, reacting in their different ways to the real Labour government with its radical programmes for health, housing, pensions and education, that Laski describes with such sensitivity, wisdom and balance in her later novel The Village (PB 52), which deserves to be read at the same time as Tory Heaven.

The C’s carry discs of solid oak, for which no explanation is needed. In a quasi-symbiotic relationship, they have chosen to wait on the A’s, ‘just to be in touch with them’. These are the loyal servants whose failure to return after the war so radically upset the ease of upper-class life. David Kynaston, in his introduction, quotes from Mollie Panter-Downes’s post-war stories, Minnie’s Room (PB 34), but could have chosen several others. The C’s are the embodiment of the yearning for the past that runs through Tory Heaven. Their presence in pubs, on the far side of the bar, adds atmosphere. They are useful (overloaded) recipients of the charity that A women are required by law to distribute. But in the house they are the spies and the eavesdroppers: the Leigh-Smiths’ butler keeps them up to the mark, ensuring that they use the best silver, every day, cook ensures that they never relapse into the wartime comfort of beans on toast in the kitchen, or the sort of familiarity with B’s that they enjoyed during the war years, and miss, but dare not risk.

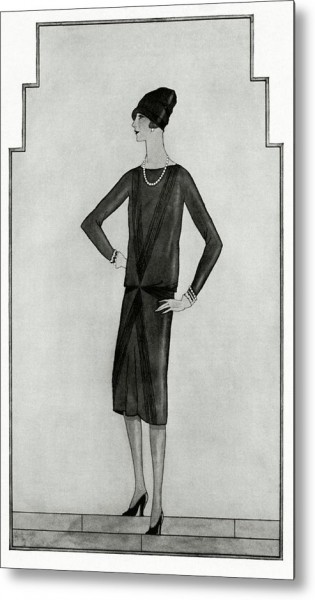

Throughout the novel the Degrading Court, which also deals with the far knottier problem of Upgrading, looms large, extending even to the wardrobe. The style police are not without power. No A would be seen dead in embossed velvet, only a little black frock and a string of pearls will do.

Rules are rules. The State must be obeyed. But this is not Fascism. Fascism, explains Ughtred ‘is a nasty foreign notion, whereas the anti-egalitarianism I am describing seems to be totally and basically English.’

D’s wear bronze discs and are Trade Unionists, but as all strikes have been declared illegal, they are no longer a threat. Wages have been cut and piecework reintroduced and their women have had to go into service once more, cooking and cleaning for the B’s to make ends meet. It sounds awfully like a zero hours economy.

Lowest of the low are the E’s, forced to carry lead discs, and casually described as ‘odds and sods’, ‘tramps, casuals and any such Intellectuals as the police may happen to pick up’. The Intellectuals having insinuated themselves under socialism into almost every position of real power, from the press, to the BBC and even the armed forces, ‘who had let themselves be hoodwinked into believing that wars couldn’t be won without the application of brain-power’, a purge has been found necessary. The Spectator and The New Statesman have been ‘suppressed’, foreign films are no longer being shown, universities have been cleansed. Intellectuals have ‘gone underground’ in their droves. Intellectuals … experts?

Relatively gentle sideswipes at entitled upper-classes, aspirational middle-classes, and fawning lower classes have been generously laced with comedy. A feminist before her time, Laski doesn’t miss an opportunity to pop the bubble of male bombast. James who, regardless of his unbroken record of failure, never questions his judgement or his right to be heard: turning swiftly away from a plain girl sitting alone at his first dance since returning home, he says smugly to himself ‘that’s the way to treat intellectual women’. He had earlier much enjoyed a conversation (if that’s the correct word for a monologue with pauses for breath) with his island companion: ‘True she did not herself say much; but the opportunities she deftly gave James for airing his own opinions or stating his own views were such as to convince him, by the time the fingerbowls were put on the table, that she was the most accomplished conversationalist he had ever met.’ I think we might say that the spirit of James lives on.

Throughout the humour and the cleverly worked out conceit of the first half of the novel, Laski has been sharpening her pen, until by the final chapters she strikes angrily at the political chicanery at the heart of Tory Heaven: ‘“Since we repealed the Reform Bill,” boasts one, ‘“there hasn’t been a Labour Party. There couldn’t be. There’s no-on left to vote for it.”’ Another dismisses the Liberals, ‘“since everyone takes it for granted that they’ll never get in, hardly anyone bothers to vote for them.”’ The Boundaries Commission have done a most satisfactory job: ‘“Manchester, for example, returns no member now, while our host here … owns two. One is returned automatically by a gazebo in the garden while the other – that for the town of Starveham – will be elected on Saturday … With the present restricted electorate, hardly anyone is likely to vote other than Tory.”’ When James questions the legality of his eventual degrading, he gets a dusty answer, ‘“Whatever benefits the State is legal and if it isn’t today – retrogressive – I mean, retrospective – the law will see that it is tomorrow.”’

A few days ago, the former Tory leader, Lord Howard said, ‘I think that judges have increasingly substituted their own view of what is right for the view of Parliament and of ministers.’ We can almost hear Marghanita Laski’s melifluous voice with its clipped vowels and careful intonation (troublingly similar to Margaret Thatcher’s!) admonishing us: ‘Don’t say I didn’t warn you.’