Triggered by a need to set the record straight on an old love affair, Tirzah Garwood began the first draft of her autobiography in March 1942. She was recovering from a mastectomy, an even more radical operation then than it is now, with a longer period of convalescence, which, with the life-affirming optimism that pervades Long Live Great Bardfield, she declares she very much enjoyed: ‘… it has made it possible for me to write this account of my life which otherwise I should never have had time to do.’ The first handwritten draft was completed by the end of May – more than four hundred pages in just over two months. ‘This is gunpowder,’ warned her husband, Eric Ravilious, fearful (with reason) that her ‘indiscretions might lead to trouble’ or horrify their children.

When she came to type up the manuscript in February 1943, Eric Ravilious was dead. Sent to Iceland in his capacity as War Artist, within a matter of days he was declared missing, then presumed dead, after the plane in which he was a passenger came down in the Arctic Ocean. Self-censoring, perhaps mindful of his warning, she cut many references to her personal life, and to Eric’s affairs, and to hers. Happily for us the original notebooks survived. Her daughter Anne, eighteen months old when her father was killed, and not yet ten when her mother died in March 1951, has seamlessly pieced together the typescript and the notebooks into a vivid (self) portrait of her mother, her father, their marriage, and their circle of friends, and an age, an inter-war period of radical change, questioning and rejection of conventions, social, sexual and artistic.

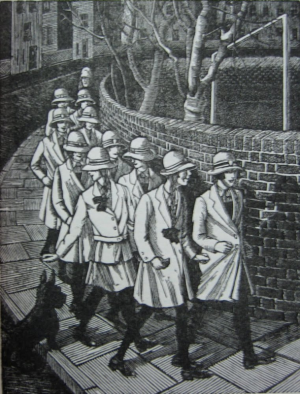

Tirzah rattles through her early years – actually she rattles through most of her life – pausing to expand on events or people who were important at the time, or amusing in retrospect. In a vivid example of childish puzzlement at the behaviour of adults, she recalls a shared governess who encouraged her charges to make wool balls. ‘One of the little boys died and as I was very quick at making wool balls and loved doing them, I finished his off as well as my own. One day I was dumped on his mother’s doorstep and told to give her the ball; quite unembarrassed, I explained that I had finished Michael’s ball and was very surprised to be so effusively thanked and kissed for something that had after all been a pleasure to me.’ And she sympathises retrospectively with her piano teacher, who started every pupil off with Grieg’s Albumblatt, ‘I suppose the whole business of teaching being painful, it was less painful to hear one piece continually murdered than a large number. Once he kissed one of his pupils and after that we had to have a chaperone in the room during our lessons. In spite of this, he managed to marry one of the girls after she had left and then quite suddenly he died.’ Speaking in her child’s voice, or that of the knowing adult, her style is so immediate, so matter-of-fact, and her wit so succinct and so dry, that we might be reading a collection of letters, or eavesdropping on a conversation, as she recounts the attempt of the headmistress of her smart boarding school to join with another, less prestigious – ‘she had as much hope of amalgamating West Hill to a school full of girls who talked with Midland accents as she would have if she tried to amalgamate it with the Tiller Girls.’

Tirzah’s background was traditional upper middle-class, with a dash of eccentricity: nannies, governesses, boarding school balanced by a streak of dottiness in her father. Colonel Garwood was a man of frequent and changing obsessions: at various times an enthusiastic amateur poet, playwright, actor and archaeologist. He shared a (competitive) love of painting with Tirzah’s mother, who was also an accomplished photographer. They put up no resistance when she chose to go the local art school, and when, aged twenty, she decided to move to London, they were easily persuaded, seemingly heedless of the fact that she was quite unprepared for independent living – on arrival at the Ladies’ National Club in Kensington, she had to be taught by a fellow resident how to make tea. Her father’s one anxiety was that she would ‘soon start living with that fella Ramvillas’.

Ravilious was not the son-in-law the Garwoods would have chosen. Her first “love”, a Cambridge educated civil servant, son of a neighbouring military family, was more to their liking. Tirzah offers a wonderful pen-portrait of the prevailing ideal, the young man of her older sister’s dreams: in the 1920s, ‘for a man to pass the test of being attractive was a tricky thing. They must have been to a public school and be able to dress well, a soft hat turned up was the sign of a boob and a bowler hat was seldom tolerated except in London. They must not be too handsome, hair set in waves was very wrong and of course it was better to be athletic than clever. Height was almost essential, if men were small they must be very rich, very amusing or a double blue.’ Bob Church ticked most boxes.

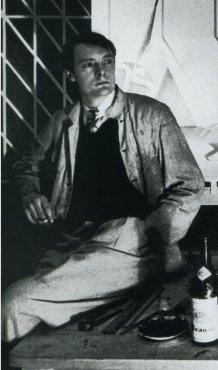

Eric did not. He was the son of a Methodist preacher with an unpredictable temper and an uncertain income. His mother, having held the family gently together, had hoped that her youngest child might, on leaving Eastbourne Grammar School, ‘go into something steady like the Post Office.’ That he might become an artist wasn’t even thought of – his friend Edward Bawden’s parents having hoped their son would carry on the family ironmongery business, were similarly disappointed. Tirzah met Eric when she was seventeen and he was twenty two. Having rejecting his mother’s plans for him, and studied at the Royal College of Art, by 1926 he was commuting regularly from London to teach at Eastbourne College of Art, where she was a student. With typical frankness Tirzah describes her first impressions: ‘He had a smart double-breasted suit and shy, diffident manners not unlike those of a curate and, with my family’s training behind me, I quickly spotted that he wasn’t quite a gentleman.’ In spite of this, she soon recognised that: ‘Bob stood for my family’s idea of a life and Eric for my freedom and independence’, freedom not just to pursue her own career, but, as it later turned out, to pursue her own love affairs, as Eric pursued his. Recording their marriage in 1930, she writes: ‘I felt quite sure I was in love with Eric by now and we neither of us felt apprehensive at having to make so many solemn promises.’ They did, in their fashion, love each other until death parted them, but both must have had their fingers crossed when it came to the bit about ‘forsaking all others’.

The ‘set’ to which Ravilious introduced her had at its core the ‘year of 1924’ at the RCA, a group which, in addition to Eric himself, included Edward Bawden, Enid Marx, Percy Horton and Peggy Angus, and a growing number of friends and lovers. Andy Friend in his book Ravilious & Co writes that ‘friendship merged or sparked into love, often regardless of marriage ties, with predictable complications, and their ethos was predominantly heterosexual, rural and national.’ This set didn’t live in squares (or love in triangles).

In his introduction to Ravilious & Co, Alan Powers described the mood of the group as being ‘one of levity and hedonism both in life and art, a release from the oppressive weight of growing up during the First World War that was noted as characteristic of a whole generation.’ Tirzah and Eric’s life together was to be book-ended by two wars. The urgency of her writing reflects the times in which they were living, working, and loving.

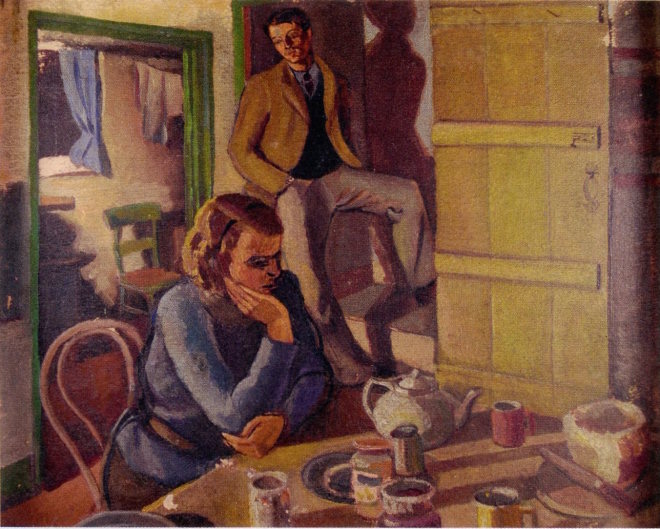

Extra-marital affairs were far from unusual amongst their friends, and they seem to have been remarkably frank with each other concerning their own, and exceedingly tolerant. When Eric falls in love with Helen Binyon, daughter of the poet Laurence Binyon, Tirzah is phlegmatic, ‘I knew that under the same circumstances I should in all probability have behaved in the same way and I couldn’t blame Helen for taking him away from me, because Diana [Low] had already done so.’ Contemplating an affair with John Aldridge, she asks Eric’s opinion: not a good idea, he says, but seeing that she has made up her mind.… Further consulted, Eric draws the line at her having a baby with Aldridge: ‘and I saw that it wasn’t really a good idea.’ One would like to know more of that conversation!

‘I had been so pleased with the discovery that I could still be fond of Helen although she and Eric were in love with one another and that I could love Eric and Bob [she briefly resumed her pre-marital love affair with Bob Church] and John all at once and for different reasons even though they loved other people as well because my loving them was the important thing and not my possessing them. I didn’t believe in that hateful term ‘Free Love’ because obviously you have some sense of responsibility towards those people you love. Oh how I detest blame.’ Philip Larkin was wrong, sexual intercourse did not begin in 1963.

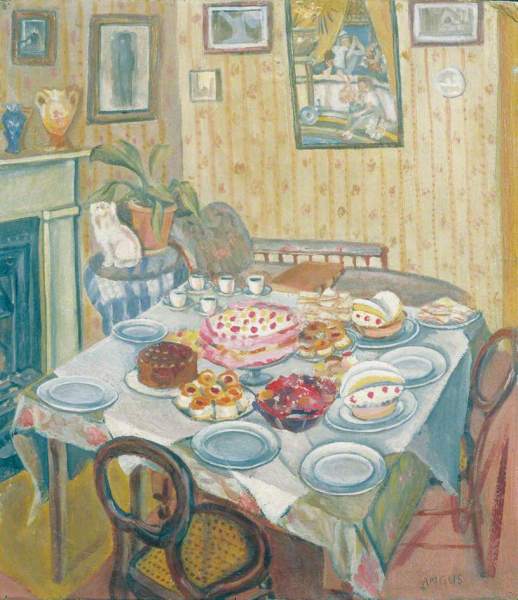

‘… It seems almost impossible that people could cram so much work and entertaining and visiting into one year …’ to which she might have added love-making. Tirzah is writing about 1933, but the same comment might apply to every year. Though they had first a flat in Kensington, then a house by the river in Hammersmith, the young couple seem to have been always on the move, dividing their time between London and Great Bardfield – first in a house shared with the Bawdens, Edward and Charlotte, not easy housemates. Then, in 1934, for £50 a year, half their London rent, they rented their own house nearby. Bank House had gas (they would put in electricity), a bathroom and a lavatory – luxuries, especially the lavatory. Previously they had made do with water pumps and outdoor privies, shared with visitors, who arrived often and in numbers too large for the available beds, requiring eiderdowns to be spread out by Tirzah on the sitting room floor. When Eric embarked on his first affair, poor Tirzah blamed herself, ‘I was no fun and did nothing but housework’. Little wonder.

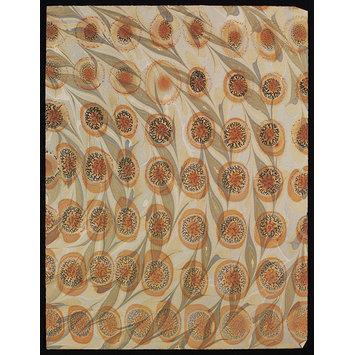

Staying away offered some respite, new images for Eric, and a chance for Tirzah to do her own work. Peggy Angus apparently didn’t mind her installing a paper marbling bath on the copper in the scullery of her Sussex cottage, because she ‘provided the wallpaper’. Tirzah’s marbled papers are very beautiful. But where did they wash up?

The period details are both wonderful and puzzling. A second home in Essex meant a three and three-quarter hour coach journey, or train and hired bicycles. A ‘shiny black Morris Eight’ bought for £70 made the journey to Wales easier when Eric wanted to paint mountains, but home comforts there were not. In the early days of their marriage, a ‘char’ came in daily, but missing three fingers, was unable to cook. Eric fried the breakfast bacon and Tirzah did the rest. They played rummy to determine who would wash up, which sounds more fun than loading a dishwasher. More than once Tirzah cheers herself up buying silk to make French knickers. Did our mothers or grandmothers do that?

There isn’t a page in Long Live Great Barfield which doesn’t surprise, make one smile with amusement or delight at this tender picture of a complicated marriage, perfectly summed up in Tirzah’s thoughts after Eric’s death: ‘…I had never felt unfaithful to him if I loved other people because so long as he knew and approved of them, there was no necessity. The good thing about our marriage was that we had at any rate been truthful towards one another.’