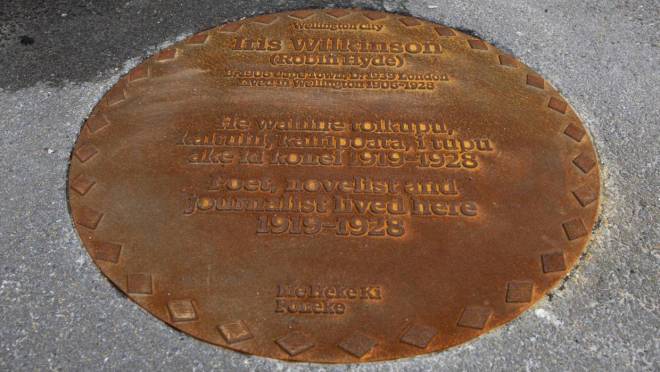

A plaque was placed recently in Northland Road, Wellington, New Zealand: it commemorated the life of Iris Wilkinson.

Her family had acquired No. 92 a hundred years earlier, on the proceeds of her father’s World War One pension. Northland Road represented a step up for the previously peripatetic family, and for Mrs Wilkinson affirmation of their middle-class status. The house, with its affectations and its occupants, is sketched with the succinctness, wit, and sensibility that characterise this remarkable semi-autobiographical novel.

‘At Laloma the sitting room was called the drawing room, and the scullery was the kitchenette. John, who had ceased to sleep with Augusta in the double bed, had a little blue room to himself at the back of the house, his window opening on a dank pit known to Augusta as “the fernery”. Augusta and Kitch, Carly and Sandra, shared bedrooms, and Eliza had a tiny green room of her own, technically because she was studying for her senior scholarship, actually because she was restless and made things unbearable for everybody.’

Iris (Eliza), better known to us by her nom de plume, or nom de guerre, as she preferred to call it, Robin Hyde, was twelve years old at the time of the move, and enrolled at Wellington Girls’ High School. Katherine Mansfield had been a pupil there from 1903 to 1905 and Ann Thwaite, in her Persephone Preface to The Godwits Fly, lists the many parallels in the lives of the two writers, both growing up in Wellington: ‘the ill health, the insomnia (with its resultant drug dependency) and they were both rebellious, impulsive, reckless, amoral, depressive, hurt and bruised by life.’ But there were significant differences. Katherine Mansfield came from a prosperous upper-middle class family, who arranged for her to complete her education in London, and when in 1908 she expressed her wish to return to England, she was allowed to do so with a yearly allowance of £100 (equivalent to over £10,000 in 2019), later increased to £300. Once there she soon found herself mingling with the cultural ‘aristocracy’ of the time.

Iris was already thirty-two when (fulfilling both her own long-held dream and, vicariously, her mother’s) she arrived in London, after a long and tortuous journey via China, thirty-three when she killed herself in a Notting Hill Gate bedsitter, in August 1939. She had few friends and very little money. Though her literary reputation was such that news of her death appeared in the New York Times and the New Zealand High Commissioner spoke at her funeral, declaring that ‘In the midst of the important affairs of state we must make time to bury our young poet’, she had not been taken up by the London literati, preoccupied perhaps by those very affairs of state.

She had left school to begin work on a Wellington daily paper at the age of sixteen, and for some years enjoyed considerable success as a journalist. Since childhood, Iris had filled notebooks with her poems, but she was twenty-three before her first collection of poetry was published, and nearly thirty when her first novel appeared. The Godwits Fly, her fifth and last novel, was published in London not long after she reached England. It didn’t sell well, and was not republished in New Zealand until 1970, and not until 2016 in the UK, by Persephone Books. The New Zealand critic Mary Paul, who has written at length about Robin Hyde, as we must now call her, puts this down in part to timing: ‘by the time the war had ended it was a different world and writing and nationalism were moving on.’ Some contemporary reviewers considered her writing to be excessively mannered. The Godwits Fly is not a conventionally easy read.

Is it a novel? Is it a bildungsroman as some have suggested? The narrative thread, such as it is, lies in Eliza’s account of her life from her early childhood until the age of twenty-one, a considerably reworked version of an earlier therapeutic exercise in autobiography. Following a suicide attempt in 1933, Robin Hyde had been briefly confined in Auckland Mental Hospital, and subsequently lodged there for four years as a voluntary patient, while continuing to write poetry, fiction and journalism. Her doctor, Gilbert Tuthill, to whom she would later dedicate The Godwits Fly, was a pioneer of the newly fashionable ‘narrative treatment’, a variation of the talking therapies being used by European psychoanalysts. It was expected that in the retelling the patient would better understand the trajectory of their life. Or hone it to their satisfaction. ‘This imperfect part of truth’ are the words Hyde uses in her dedication to Dr Tuthill.

A bildungsroman is presumed to focus on the psychological and moral growth of its protagonist, but Hyde appears to be seeking proof of consistency rather than development. Eliza’s reckless disregard for boundaries as an adult is no different from her defiant venturing on to the forbidden clifftops as a child. An argument with her landlady over an electric light-bulb springs from the same source as a dispute with her netball teacher, and generates the same satisfaction, ‘these small wrathful encounters were in their way the spice of life.’ A contempt for rules is as much a part of her as her preference for conflict over compliance. She doesn’t grow into them, or out of them. The childhood chapters cover childish things: her dolls, characteristically christened with grandiose names, Athene, Andromeda, Perseus, and Cressida, and equally characteristically unwashed and unloved; her fascination with her neighbour’s hair tidies, and cuckoo clock; a deep desire to believe in fairies. But she seems to have observed them, at the time, through adult eyes. She expresses no innocent puzzlement at her mother’s reaction to moving, which ‘used up all her softness, all she had in hand besides fortitude and pride.’ The child overhears her parents’ arguments, while the woman interprets them. A complex, sophisticated, and strangely lyrical description of the shackles of marriage concludes with painful simplicity: ‘They share a double bed, and have children. One day an ageing man looks round, and finds himself wrestling with an ageing woman, her face seamed with tears.’ Eliza the little girl and Eliza the grown woman are both present in the early chapters, and the little girl will make occasional appearances in the later ones. Perhaps not strictly a bildungsroman?

Is it a novel? In some ways it resembles a collection of short-stories, and I say that hesitantly, knowing the resistance of many Persephone readers to the genre. Each self-contained chapter can be read virtually independently of the others. The Hannay family, Eliza, her sisters Clara and Sandra, her parents Augusta and John, and later Eliza’s great friend, Simone, her lover Timothy, and Clara’s not quite fiancé, are the links, sometimes taking centre stage for an entire chapter – Hyde slips brilliantly inside their heads and assumes their voices. Other characters emerge fleetingly from the shadows in one chapter, then disappear. As in life, we cannot be sure if they will prove of lasting importance. Some recur only in an incidental mention of their death. These are neighbours, relations, teachers, schoolfriends, passing political acquaintances, fellow patients, all brought vividly to life, sometimes by the smallest detail: John’s friend the harness-maker who ‘had a silver mop of hair, like an albino golliwog’; Mr Potocki, ‘who had a gymnasium class, and got drunk, thought he could fall off the roof without hurting himself’; Dr Trovey ‘who makes toffee in his room after hours’; John Hannay’s friend, Hairy Harry, who kept a fruit stall and hoped ‘there would be a Labour Government one day, much as a patient snail may hope for the abolition of thrushes.’

We meet an entire clan of uncles, aunts and cousins in Australia: Great-Uncle Gervase, from whose chin protruded a whisker so fine and wavy that it looked as if he used it to feel with, like the antennae of a moth’; Aunt Bernardine who wore a rainy tremble of amethysts on her fingers and her long white throat’; bachelor Uncle Rufus who wants to adopt the Hannay children, but of whom we hear no more for two chapters, when Augusta buys a piano with ‘more than half the money’ left her following his death at Gallipoli.

Major historical and family events are dropped anecdotally, en passant, into the narrative: ‘… in all the butcher shops, pink-rinded German sausage, with the delicious little triangles of bacon fat, had become “Belgian sausage”’… Eliza is sent down the street to spell out the war news to a blind neighbour, laboriously pressing with her fingers against her hands the words ‘British Victory’. The dim outline of a rocking cradle announces the presence a fourth child in the family. Eliza and her sisters are sprayed at the village hall, school is shut up and ‘many of the Duffel Street children were dead or dying’, the streets smell of formalin. Time passes unevenly and unrecorded between chapters, leaving gaps in which babies are born, war begins and ends, Spanish flu reaches the Southern Hemisphere. Eliza endures the loss of the man she loves, the darkly attractive, wayward Timothy, and suffers a life-changing accident, and a nervous breakdown: we do not learn when or how or of what nature.

Robin Hyde describes loss, pain, disappointment, change and sorrow in a few words. Her mother’s defining lifelong yearning for an England she has never seen and which stands for everything that has been missing from her life, is first mentioned in brackets, as part of someone else’s story – ‘(Augusta’s beloved, unattainable England)’. We deduce the end of Carly’s long ‘understanding’ with the ‘obdurately selfish’ Trevor from her loss of interest in the lovingly filled ‘glory-box’, her trousseau. Eliza barely mentions her still born child, ‘He’s little and lost and hasn’t got an identity, only a face, and I’m almost the only one who saw it.’ Heartbreaking.

But Hyde is brave. With the same brevity, gently, but with resignation, and wit, she reflects on men and women, love, marriage, children, making us smile in recognition as swiftly as she moves us to tears. Puzzled as a child by ‘the funny, darkling world of boys’, who lived by different rules even in the school playground, Eliza never reconciles herself to the social assumptions of inequality. The ‘value of men to women was plain in everything they did … The value of women to men was debatable. If women weren’t there, Eliza had a feeling the men would continue to talk shop for about ten years before they noticed anything. Then presumably, they would want some fresh tea … or to reproduce their kind’, the burden of reproduction falling most heavily on women: ‘Kitch was still [Augusta’s] little boy, passionately in earnest over model aeroplanes, generally quiet and good. But when the time came he’d present his bill, the bill you get twenty years after the gasping agony of giving another individual life.’ Writing the Woman’s page on a local newspaper only fans the flames of Eliza’s rage, ‘razoring from foreign exchanges anything that might be taken as a hot tip for women (generally assumed to be darker than Erebus in matters of cleaning their pores, curing their children of spots, keeping their man). She read the sex blackmail of a thousand advertisements – even your best friend won’t tell you.’

She finds solace in the absurdities, and foolish pretensions of everyday life: the school play, ‘in French, so that parents could see they were getting their money’s worth’; the rigid hierarchy of the church congregation, nearly all related or connected by marriage: ‘one built the church, another held the mortgage on it, a third was Sunday School superintendent, two were churchwardens, and the broken reed of the family worked as janitor’; Eliza’s best friend Simone’s father made so furious by the smell of depilatories that he threatens to thrash her.

More than anything she is consoled by nature. Robin Hyde, the poet, pauses the narrative to linger over the fall of a butterfly, or the flight of a bird, not only the migrating godwits of the title, but quails and skylarks, parakeets and pukekos and Old Red-Nose-Hiding-in-the-Mango. Eliza revels in the colour and the texture of the toi-toi, the macrocarpas, the pohutukama, – such stirringly strange names: New Zealand is a very long way from England. Augusta, in so many areas uncomfortably bound by convention, and demanding the same of her family, yearns to grow things, to be surrounded by flowers ‘disorderly with the rich and perfect disorder of the cultivated thing that knows how to let itself go’.

The Godwits Fly is a wonderfully rewarding read, best taken a chapter at a time, and then opened again, and again, at any page to savour the delight of the detail, or to smile at an unexpected turn of phrase. In Mary Paul’s words, Hyde’s work needs careful reading, not special pleading.