“Thank you, Upjohn”: Mary Winthorpe receives the news of her husband’s death with an equanimity bordering, in the housekeeper’s view, on the unseemly. Upjohn seems unaware that her solemn announcement might conceivably be a cause for celebration. ‘Never again to have to kiss him goodnight! After fifty-three years of having to kiss him …’ Having to kiss him … what sort of husband was the Colonel? And what sort of father? His eldest son, woken next by Upjohn (mindful of precedence), is anxious only to know whether or not the old man had asked for him. Jack is not seeking evidence of paternal affection but rather an indication as to the likelihood or otherwise of his being cut out of the will. His wife, an actress, half his age, and the cause of his probable exclusion, is momentarily almost tearful, but rapidly conjures up a most comforting mental picture of their future: ‘Now they would be able to afford a big house, a swimming pool, maids a car …’. Laurine says only, “I hope he didn’t have any pain …”

Upjohn’s third tea tray is for Jack’s younger brother, her favourite, and we assume his father’s: Jack, the artist, being unwilling or unable to take on the conventional role, Harry, improbably, has been running the estate, improbably because, knowing next to nothing of the Colonel, we have already assumed him to be something of a bully, and a resolutely alpha-male, unlikely to approve of a son whom we meet first sitting up in bed, crocheting. ‘The bedclothes were pulled comfortably up over his stomach, already full with approaching middle-age, and on his knees rested a pattern which he had fastened with drawing pins to a small pastry board.’ Vain Shadow opened with news of a death and by page 4 it is clear that we are in the realm not purely of tragedy but of comedy too, already signposted by Laurine’s reveries. We can picture Harry’s plump hands carefully tapping the drawing pins into the pastry board, not just any pastry board but a small pastry board. Why does the smallness somehow make it funnier? We are unsurprised when, having first, respectfully, turned off his wireless, and wound up the crochet cotton, (‘“You could always depend on Mr Harry to do the right thing”, thought Upjohn, aware that almost before her back was turned Mr Jack had moved ‘with rising eagerness to kiss Laurine’ – clearly not her idea of the right thing ) he goes straight to his immaculately tidy dressing table for his spectacles and his gold propelling pencil and draws up, with absurd precision, a ‘to do’ list for the day, starting with:

Inform Family

Children

- Jack (& Laurine) – present

- Self – present.

- Brian (& Elizabeth)

No brackets or & after Harry: Harry doesn’t share his older brother’s enthusiasm for women.

The list helpfully introduces us to the whole family, three brothers and a grand-daughter, Joanna, with a bracketed husband. Joanna we discover only later is the daughter of the youngest of the Winthorpes’ children, Sylvia, who died young, abandoned by her husband, leaving her only child to be brought up by the grandparents. The family will gather for the funeral of Colonel Winthorpe, husband, father and grandfather, the ‘vain shadow’ of the title, but none will mourn him. Harry reflects, coldly for a newly bereaved son, the only one to have remained in the family home: ‘Strange to think how the Old Man’s voice had droned on through the years and one actually noticed it more now that it was silenced – like a clock whose tick was so familiar that one only became aware of it after it has stopped.’

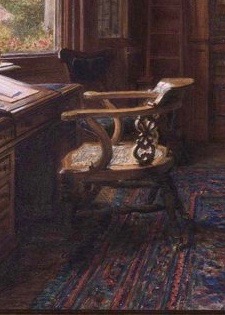

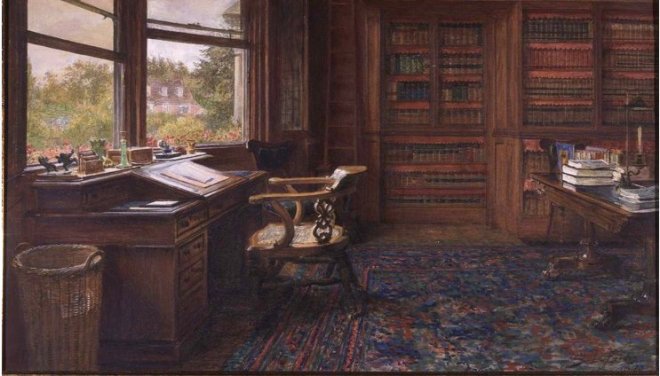

A formidable absence, framed by his empty chair, the old man is central to the novel, but Jane Hervey leaves us to piece together only a patchy portrait, from the private thoughts of his widow, his sons and his granddaughter. Joanna ‘sees’ his ghostly form leaving the dining-room, a large man, with unexpectedly small, neat feet, thick white hair, wearing a plum coloured worn velvet smoking jacket.’ Mrs Winthorpe ‘hears’ his cough, his barking voice, his heavy footsteps and the tap of his walking stick’, and cannot escape the loathsome smell of his cigarettes. Neither woman can free themselves from ‘the old familiar sense of fear’, never fully explained, nor discussed, any more than Joanna’s unhappy marriage, wretchedly mirroring that of her grandmother. The two women should be closer than they are, but the Winthorpes don’t go in for closeness.

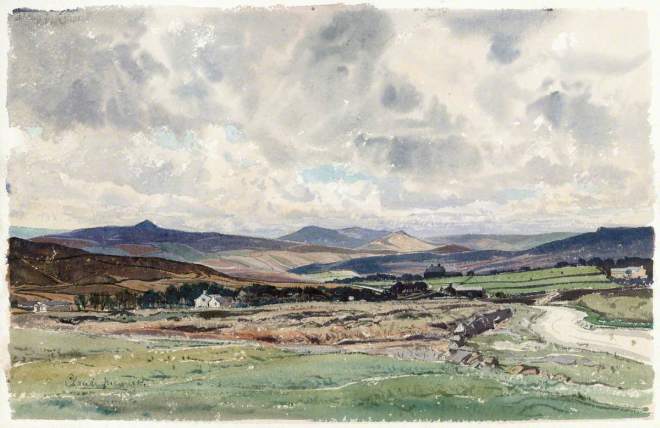

Apart from the funeral arrangements, transport, dress code and funeral meats, and later the will, worryingly little is discussed, or appears to have been discussed in the past. The reader is left to pick up hints about the Colonel’s life: heir to a large estate, in post-war decline, reflected in the reduced acreage of vegetable garden and the emptiness of four out five greenhouses. An army career of sorts must have followed. Skinless, eyeless trophy skulls ‘decorate’ the hall, trophies from a Canadian hunting expedition (or two, or more). A cabinet is filled with abundant gifts of jewellery, atoning, we surmise, for multiple marital misdemeanours. That he disliked local society hardly needs saying, nor that ‘he dislikes a talker’, and ‘doesn’t like’ the neighbouring vicar: Mrs Winthorpe disturbingly speaks of him in the present tense, but admits to not knowing what part of his estate he loved the best.

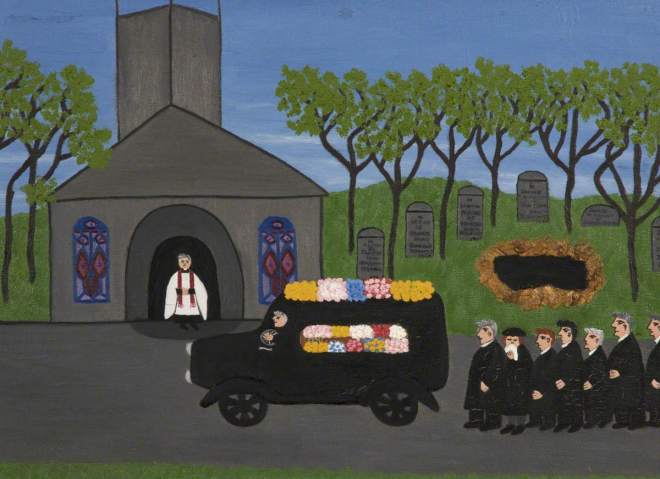

Brian the youngest of the brothers announces that their father had expressed a wish to be cremated, to the irritation of his older siblings, Harry because he has made such meticulous arrangements for the burial, and Jack because he considers that, as the eldest, he should have been the recipient of such an important message. Bereavement exposes rather than resolves cracks in family unity, as the old dynamics reassert themselves. When Brian irritates their mother by inviting elderly cousins to share in an already overstretched lunch, ‘A small delight rubbed guilty hands and smiled in Jack’s mind, just as it used to when they were boys and he was not the one to be punished.’ Hervey is sparing with the back history, but offers a few telling vignettes, some sad like Mary Winthorpe’s humiliating honeymoon exposure to Parisian nightlife, others like Joanna’s girlish pranks against Harry, tying up his entire room with string, and putting Eno’s salts in his chamber pot, more entertaining. Harry, of course, still bears a grudge.

Funereal solemnity is not always easily maintained, in the midst of the banal practicalities. Comedy has a way of reasserting itself. How loudly might the breakfast gong be sounded? Who will be the first to sit in the empty chair? Is the luggage lift an appropriate vehicle for removing the body from the house? Should Laurine pin her treasured diamond brooch to her black hat? “It’ll look like one of those things a doctor wears on his forehead when he looks at your tonsils” is Joanna’s blunt reply. How long before the ashes are cool enough to collect? Would the Colonel’s cigarette box be a suitable container in which to inter them – the scattering option having been rejected on the grounds that the charred remains of a neighbour had most unfortunately blow back in the faces of the scatterer? Can the journey from church to crematorium be made in the time available, without jeopardising not only decorum, but the ties securing the flowers to the top of the funeral car?

The novel’s title would have resonated more powerfully when it was published in 1963 than it does now, when Psalm 39 no longer regularly forms part of the Funeral Service. Too gloomy for modern taste.

…verily every man living is altogether vanity.

For man walketh in a vain shadow, and disquieteth himself in vain : he heapeth up riches, and cannot tell who shall gather them.

Jane Hervey acknowledges the original meaning of the words, conveying the emptiness of our lives and the futility of material ambition, and at the same time plays on contemporary usage. For fifty-three years Mary Winthorpe has lived in her husband’s shadow and it still looms large. ‘It was as though Grandfather was still there, perhaps always would be there, somewhere waiting to pounce.’ In the background too is the pale shadow of Sylvia’s mother. ‘If only I could tell her – tell someone – if only my mother were still alive!’ Joanna longs for reassurance that leaving her husband is the right thing to do. Mrs Winthorpe spots an old flame at the funeral, ‘like looking into the windows of a strange house at a friend overshadowed and made unrecognisable by the altered surroundings … that young man was dead, quite killed by Charlie himself; and with him died another part of her …’

The psalmist was only partly right about riches in the Colonel’s case. Winthorpe has made quite clear who is to gather his riches, although suprisingly his will allows for a generous interpretation by the brothers, belying the old adage ‘where there’s a will there’s a war’. Interestingly it reveals a more humane and understanding aspect to him, a facet not spoken of, or hinted at by his heirs, even in their many unspoken ‘asides’. Perhaps after all he had seen something in Joanna’s marriage to which the others were wilfully blind. The will opens up the future. Four chapters, four days, from death to interment of the ashes, in which time has been temporarily suspended. At the end of the fourth day life starts again for the living.