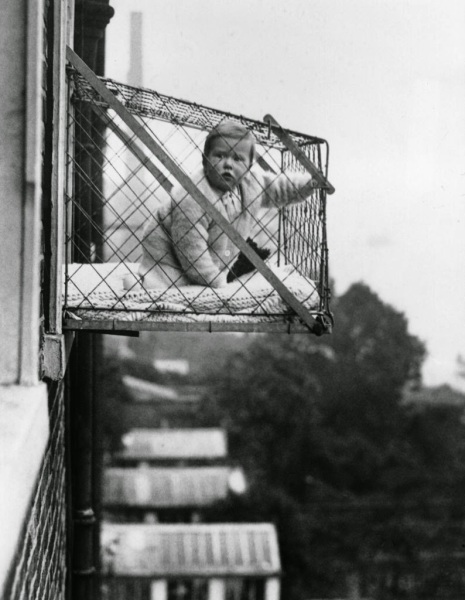

Enid Bagnold described to her husband the sensation of having a new baby as being ‘like having a tiny lover out in the pram’. The italics are mine: in the age of the ‘close baby carrier’, it is astonishing to be reminded that until the 1950s ‘out’ was where most babies spent most of their days.

Enid Bagnold married in 1920, at the age of thirty, late for the period, and with some well documented affairs behind her. Her husband, Sir Roderick Jones, was forty-two. It would be a contented if far from passionate marriage, open and resilient enough to bear talk of lovers. The couple had four children, the youngest, Dominick, born in 1930. For years she had nurtured the idea of writing a novel about childbirth. Published in 1938, The Squire was the product of a long gestation, closely and vividly based on her own experiences, of pregnancy, birth and motherhood, as well as love, marriage, ageing, and the strength of women, from the squire (so dubbed in the temporary absence of her husband) to the housemaid. But, above all, it is about the Baby, its last days in the womb, its birth, and his first month. Only the direction of a wedding ring spinning on a hair might (or might not) suggest, in those pre-ultrasound days, whether ‘it’ would turn out to be a ‘he’ or a ‘she’.

The Squire opens with the household waiting ‘in restless suspension and slightly growing indiscipline’ for the Unborn, the capital letter awarded, and indiscipline silently regretted, by Pratt, the curmudgeonly butler, a character who, in a small way, bears comparison with some of the greater literary butlers, Raunce in Henry Green’s Loving, and more recently Stevens in Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day. An inbetween figure, subtly powerful, and secretive, superior to and unloved by the lower staff, depended upon, reluctantly, by his employers, Pratt is modelled on the author’s own butler, Cutmore, whom she describes in her autobiography as ‘a gloomy, handsome man, a family man, but with an inborn contempt for woman.’ He has been with the squire for twelve years (Cutmore stayed twenty-four), ‘twelve years of staff difficulties’, ‘surrounded by gibbering, untruthful, slovenly women’ (his reported words), and time is passing him by, leaving him ‘embittered by the material he found around him, a trained engineer supplied with tools of tin’. How well Enid Bagnold conveys his tone of voice, as she does the voices of the ‘slovenly women’ – unsatisfactory cooks, and wilful, knowing housemaids: ‘He was no more Mr Lynch than Ruby’s eye and Ruby knew as much’, Mrs Lynch being a temporary cook, more slovenly than most, Ruby a restless maid.

The Unborn sets the pace, and the narrative, such as it is. The squire is in the last days of her pregnancy, picturing the baby, with keen expectation, but no tenderness so long as it remains unknown, ‘its arms all but clasped about its neck … closed, secret eyes, a diver poised in albumin … as old as a Pharaoh in its tomb’. How different pregnancy is now. The sex confirmed, the photo file on the laptop already filling with ultrasound images, that absolutely extraordinary brief relationship with a creature at the same time cherished and unknown, other than by its kicks and turns, is a thing of the past. A little sad.

The course of labour is so well described. None of the sudden belly grabbing followed immediately by persistent cries, as it appears too often in films, and even in the otherwise wonderful Call the Midwife. At first the squire feels only ‘a touch of pain, a finger tweaking her bowels for a second, like the thick chords of a harp thrumming in the wind’, dismissed as indigestion, then eventually recognised, but without panic. She goes to check on the other children, then settles down for a while to do her accounts. The pain (labour not torture) of the final stages is given shape and not downplayed: ‘fighting to maintain a hold on the pain, to keep pace with it, not to take an ounce of will from her assent to the passage … a little more, a little more, a little longer … she knew her way.’ And then, in a moment ‘she had the creature laid into her arms, clad already in a woollen jersey and woollen leggings’, an unappealing detail, but of its period: Enid Bagnold’s doctor Dr Waller, to whom the novel is dedicated, was a fierce proponent of wool and nothing else next to the baby’s skin for the first six months.

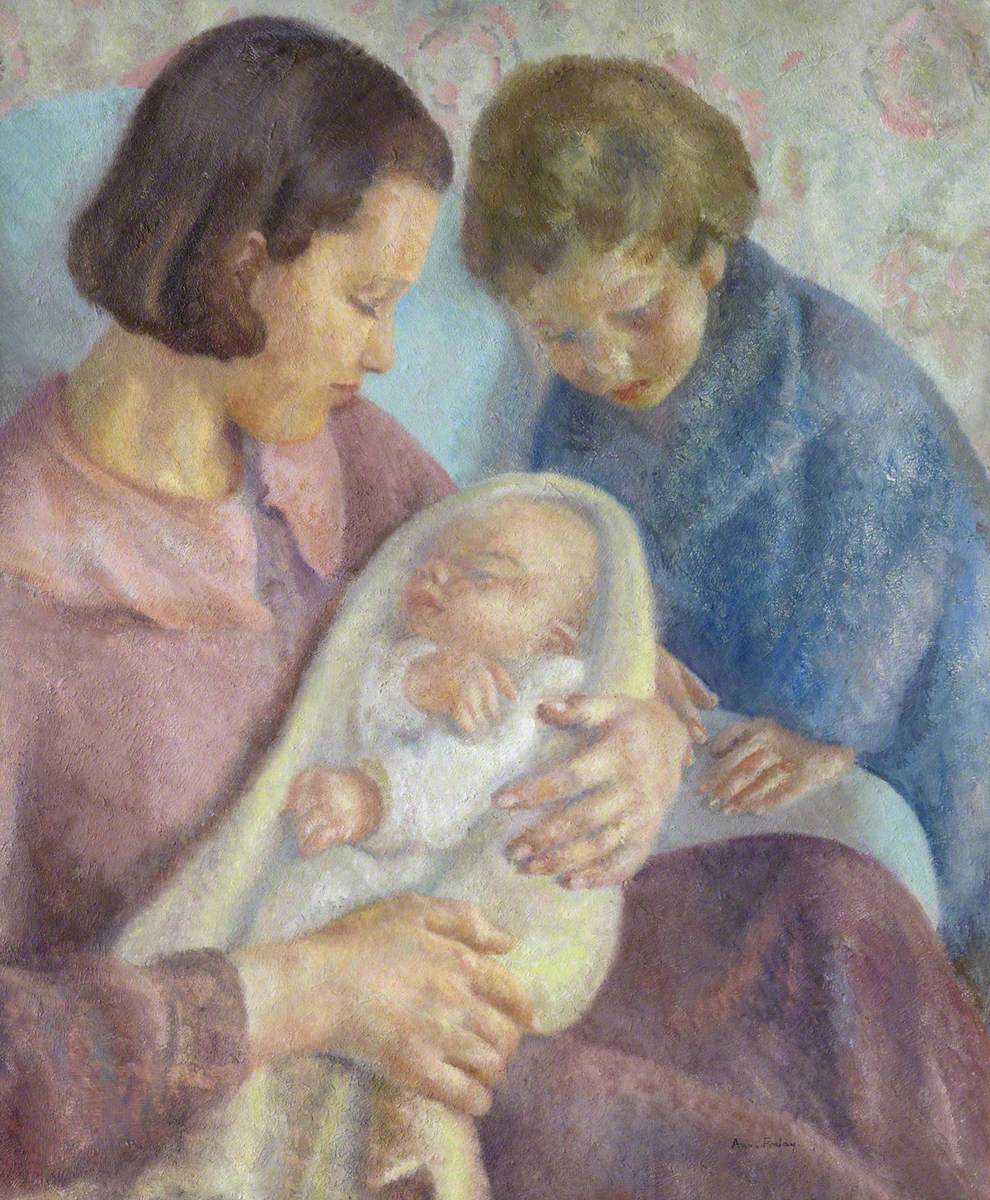

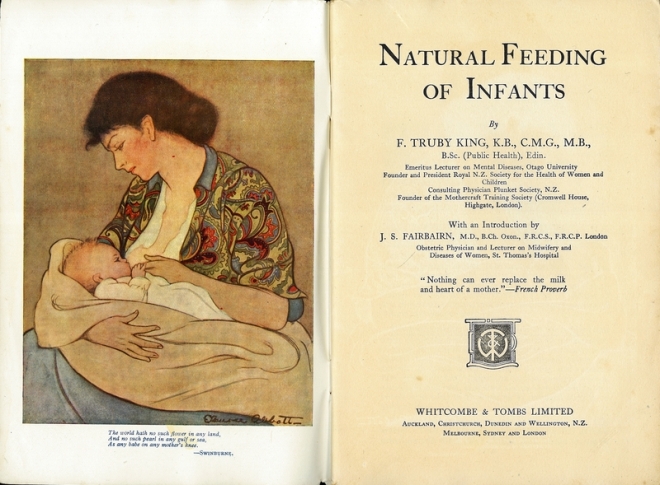

Harold Waller MD wrote at length too about the importance of breast-feeding. Bagnold’s descriptions of this are startlingly clear, shockingly so to some contemporary readers, taken aback by references to nipples, as she captures the feeling of those early intimate days, when the Unknown in the womb has transmuted into the long-awaited lover, ‘it’ has become ‘he’, his mother’s only focus. The mysterious patina, like the wonderful smell of the newborn doesn’t last. ‘Not for long would she possess the marvel of the newborn … a child in the womb, or at the breast stops time.’ It is this moment that The Squire so perfectly seizes, the moment before she begins to read over the baby’s head (a detail that many of us might recall, with a pinprick of shame), before the other children come bundling in, the oldest caring and responsible, the youngest dethroned princeling, concerned for his position. Soon the squire, loving the private intimacy of the early days with her new baby, begins to strain at the leash, ready to re-join the household and turn her attention back to her already well loved older sons and daughter.

Not for nothing were the early days and weeks after a birth known as ‘confinement’. The ‘sentence’ imposed by the squire’s midwife was four weeks, standard for the period: as late as the nineteen seventies, when my own children were born (and perhaps now?), maternity nurses were commonly called ‘monthly nurses’. For those who could afford them, or whose mothers, or mothers-in-law, like mine, both generous, and dubious about new-fangled patterns of babycare, possibly concerned too for the well-being of her son, made a present of them – Enid Bagnold ‘gave’ Cyril Connolly’s wife a maternity nurse for three months – the monthly nurse was part guardian angel, part despot. My own ‘Nursie’ was ninety percent guardian angel, but when our second baby was born, the nursery cupboard was still arranged according to her plan, and I still had a file card pinned up listing her detailed instructions for ‘topping and tailing’. Already well into her sixties, Nursie prided herself on her Truby King training. Truby King and Harold Waller, Enid Bagnold’s doctor, were the baby-care gurus of the 1930s and their views barely diverged: feeding by the clock every four hours, ten minutes each side, plenty of fresh air, no rushing to pick up a crying baby. ‘Baby’ must learn, was the underlying message, learn the rules, it’s never too early.

The squire, in a brief altercation with the midwife, unsettled by her assertion that ‘the book of instinct has long, long been closed’, makes a tentative stand against ‘the science guided baby. Labelled, its tears and stools in bottles, its measurements on a chart, its food weighed like a prescription.’ ‘Better than muddle,’ is the midwife’s curt reply. Modelled closely on the author’s own Ethel Raynham Smith, who had seen her through all her confinements, the midwife, un-named like the squire, is a beautifully drawn character, convincing in spite of being given quite deliberately no back history: bound by unspoken vows of confidentiality she can say little about her work, can neither praise nor openly criticise ‘her’ mothers (although she does let slip to the squire that her previous household was ‘wrong, or perhaps it was the mother poor thing’). Perpetually moving from baby to baby, mother to mother, house to house, she can have no home of her own, nor ties, but must ‘pass on from love to love’, hardening her heart on each occasion ‘to leave the baby she had held in the cup of her care to rougher usage.’ What an evocative phrase – ‘the cup of her care’. We know few facts about this almost ethereal woman: she has red hair, light-blue eyes, and is ‘out of the ordinary tall’ – Enid Bagnold can make the mundane magical with the spin of a word – but we feel her passion for the newly born. The growing child is beyond her sphere. ‘To snatch the newborn from the inchoate, to set it on its feet, to get the milk going, the standard in the household fixed, to hold the nebulous moment like a witch’s ball glittering with tomorrow, took all the midwife’s breath.’ The squire’s older children mean little to her, though ‘she had borned them all’ – my italics again, such a brilliant word. It is the beginnings which matter, and, however much methods of baby care may change, few would argue with her belief that ‘all is done in the first few weeks … that the perfection of his introduction to life will reassert itself again and again in all his crises …’ ‘I am virginal and narrow,’ she admits, ‘but I am his gardener.’ Asked by the squire if she has any regrets, the midwife admits to have experienced that ‘long and haunting period when the woman in the nurse is still conscience-stricken about the farewell to sex.’ ‘Men’ says the squire ‘encourage that haunting.’

Still in thrall to men, and the polar opposite to the midwife in that respect, and most others, is the squire’s younger neighbour Caroline, who describes herself as ‘a complaisant victim’, one, the squire reflects silently, ‘who could not live without attackers.’ Comparing herself to her young friend, admitting to getting ‘older and tougher’, the squire modestly accepts that she was ‘never as beautiful, never as made for love’, but more importantly, ‘never such a victim’. Although still happy to listen to Caroline’s adventures in love, and to offer advice, she feels no sense of loss. ‘There’s nothing so difficult to remember as sexual love. How often, where, and what happened? It all goes, it has all gone …’ Old lovers fade into oblivion, but the ‘tiny lover’ in the pram is more precious than any of them. Caroline may have an ‘exquisite young man, full of enemy and conspiring thoughts, moving always towards or away, but never still’ (Bagnold makes language her own – nouns become adjectives, adjectives verbs, word order thrown to the winds), but the squire has put all that behind her. ‘Here for a short while she held in her arms the perfect companion, fished out of her body and her nature, coming to her for sustenance, falling asleep five times a day in her arms, exposing its greed, its inattention, its pleasure and its peace, going red with anger in her arms, and white with digesting sleep.’

The squire finds ‘a kind of savage joy in getting to the end of the pleasures of youth.’ She watches her children passing ‘like explorers through virgin country, their hands on the door of the future.’ Their future is not only more important than her past, but far more important than her future: ‘now well past forty she was beginning to pack her box’ – what a wonderful image. Like his siblings the nameless one will stand, walk and run and make her burn with pride at the wonder of it. She pictures them all rising like expanding columns beside her. ‘Soon they’ll be past me, and I shall be walking in undergrowth, walking in a wood, sitting in a wood sinking in a wood, buried in a wood, gone.’

Reconciled rather than resigned, the squire welcomes the start of her ‘middle journey’, with renewed strength. In her way, though still clinging to youth and men, Caroline is also taking control. She may be perceived as a victim, but is learning the power of conscious collusion. The moral climate has eased, and she is free to pursue her affairs without attracting too much opprobrium. Domestic service too has changed. Positions are easily come by. Thinking of her bedroom in The Manor as a rabbit hole, the discontented housemaid knows that there are ‘a thousand others in the great warren of employment into which she could pop’. And pop she does. The midwife is stiffened by her convictions which she does not doubt: strong women all of them. ‘Her’ mothers (most of them) will care for ‘her’ babies according to the régime she has laid down, long after she has left them.

At the end of the novel, the squire having tucked up her older children, makes her way to the stables in the dark, to gather up the tiny one from his pram for his last precisely scheduled feed. No longer the tiny lover, he is learning the rules. It is tempting to say ‘poor little chap’. This gem of a novel is without question a period piece, but one which cannot fail to resonate with any woman who has given birth, and anyone who has ever watched a new mother with her new baby.