‘Don’t take the newspaper to the sitting room after breakfast,’ a friend was advised some years ago at a retirement workshop. This was I assumed, when he told me, because his wife might want to read it. But no. His wife, explained the counsellor, might want to hoover the sitting room. Why hadn’t I thought of that? Along with personal budgeting, health, and time management, some pre-retirement courses now offer ‘support for a spouse or partner through the process’. Anger management for starters?

Greengates opens in 1925. After forty-one years ‘honourable service’ at the Temple Insurance Office, at the age of 58 (so young!) Tom Baldwin is retiring. He has received no preparatory training, only a varnished oak clock wrapped in brown paper, by way of a long-service medal. As he makes the journey from Broad Street station to Brondesbury Park for the last time, having until then deliberately put the issue out of his mind, he considers the prospect of unlimited leisure, and finds it frightening. ‘It was the fear of a man who, having habitually enjoyed two apples a day, is suddenly called upon to eat six in the same period.’

Turning to the evening paper, he is unexpectedly cheered by an article on the suicide of a retired civil servant, ‘found hanging to a beam in his garage’. Tom Baldwin, like Mr Stevens in The Fortnight in September (PB No 67) and Edgar Hopkins in The Hopkins Manuscript(PB No 57), is a deeply practical man: ‘he had no garage and no beam, and he would never dare abuse the gas oven while Ada [the Baldwins’ cook] ruled the kitchen.’ With the worst of outcomes thus dismissed, he can move on to more positive, ambitious planning. Between Camden Town and Brondesbury Park, where the Baldwins have lived for most of their married life, he has decided on a new career, and a fulfilling but subsidiary hobby. He will become a Historian (capital H) and, in his spare time, radically revive the garden. There will be no doddering to the park. The fears that clouded the start of the journey have been dispelled. Had Mr Baldwin been offered retirement counselling he would surely have declined it. He has a plan. And his wife will surely love it too. ‘Edith would enjoy his retirement. Lunch together would be far pleasanter than her frugal little lunch alone. He had forgotten what a difference his retirement would make to Edith …’

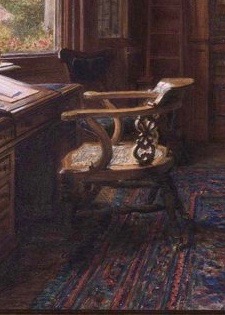

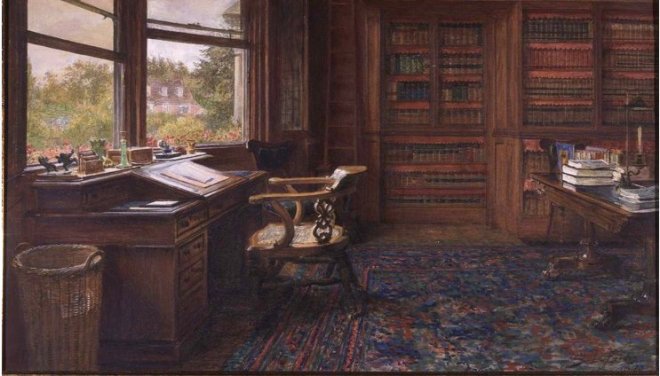

The Baldwins have been married for thirty-six years, we deduce childlessly. For twenty-eight years they have lived at ‘Grasmere’, Brondesbury Terrace, built in 1871, first rented by them in 1897, then bought in 1912 for £750. We can picture the standard mid-Victorian house, ‘a tall thin house with a slate roof and gothic chimneys’, three floors plus basement kitchen and in 2018 worth about £2 million – Brondesbury property is much in demand now, beyond the means of the likes of the Baldwins. Today’s owners would surely have a mortgage, probably have children, but definitely not be able to afford an ‘Ada’, to cook and clean, and bring up early morning tea.

‘Interior with a Woman Cooking’ 1930 by Archie Utin. Leeds Museums and Galleries

Ada, has been ‘with’ them for nineteen years. She has her routine, her kitchen, her brushes and her brooms of which she is fiercely possessive. Edith hasn’t so much a routine, as habits: reading the picture paper after breakfast, a light lunch, or ‘a cake and some coffee at Lyons’, a rest in her favourite chair after lunch, maybe afternoon tea with friends. Nine-to-five on weekdays ‘Grasmere’ has been her territory, and, to a lesser but significant extent, Ada’s. Edith has not planned for Tom’s retirement. And Tom, more than a little self-centred, while reflecting at length on his own future, recognising the pluses as well as the minuses of office life, which ‘had given him friends, and life with them outside the office doors’, football matches, and cricket and billiards …’ has not for a moment considered that his wife might not wholeheartedly embrace his full-time presence in the house, her house.

‘It was funny how Tom seemed to think that because he had retired, she had retired too.’ Sherriff, with remarkable insight into the female mind, captures Edith’s (guilty) reaction to Tom’s small but distressing intrusions. Used after breakfast to looking through the picture paper, she is taken aback to find that he has taken it. ‘It was a very little thing; just a habit – but it was the first gentle step in the ladder of her day’s work. Now suddenly this step had given way, and she was not lissom enough, on the spur of the moment, to leap this unexpected space.’ He had looked forward to a chat after lunch, when she was used to forty-winks – Sherriff knows how women speak as well as how they feel – by the fire. She must retire upstairs for her rest. Ada will have to light a fire in the bedroom. Far worse than the physical discomfort is her growing awareness of the fault-lines being exposed in their marriage, to which Tom, absorbed first in his exciting retirement projects, and later dispirited by their lack of success, appears oblivious: ‘Happily as they had always lived together, she knew today more clearly than ever before that this happiness depended upon a regular, daily period of absence from each other. … she knew that they had no deep well from which to draw their mutual interests.’ Edith worries about Tom, and their marriage. Tom worries about himself.

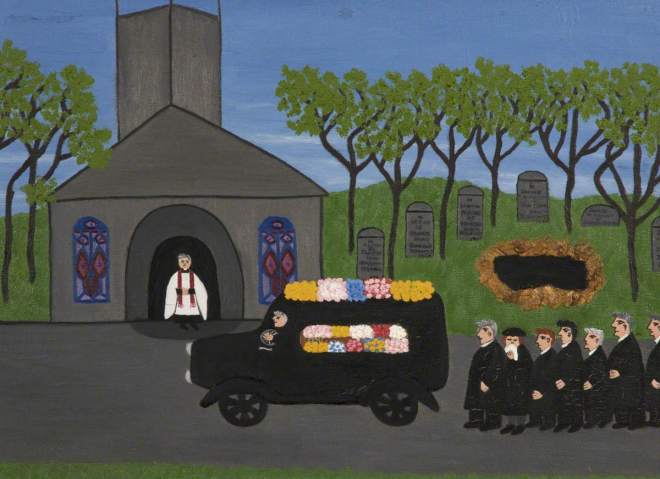

One year on from his final commute, and the neighbours have come to view him as a figure of fun, a tragic figure even: ‘Sort of old boy who’ll drown himself one day.’ ‘They’ve had another row,’ they say, seeing the old couple return from another cantankerous shopping expedition. Hopes for a happy, or even a bearable retirement seem to have evaporated, when Edith remembers a walk they used to do before the war, and bravely sweeps aside Tom’s curmudgeonly objections, the bus-fares, his lumbago, the hot train, the cold night air. They would follow the old footpath across the open fields, rising through the woods between Hendon and Stanmore, to the North of London.

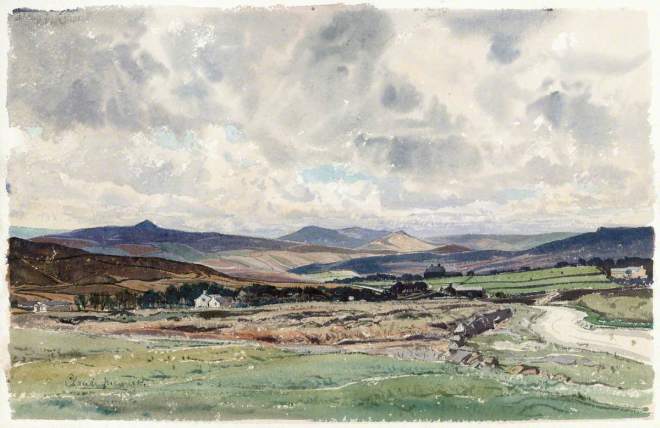

They had last walked that path before the War. Lloyd George had promised a ‘land fit for heroes’ for returning soldiers and the 1919 Housing Act had enabled local authorities to build council houses. By the mid 1920s private developers had begun to take advantage of plentiful labour, low interest rates and a good stock of available land. The Baldwins are shocked to find their much loved Welden valley filled with small new houses, and more being built at the top of the hill. But dismay rapidly turns first to curiosity and then, magically, to delight.

And there is something magical about the keen young estate agent, who appears almost instantly to show them round the enchanting (it’s tempting to write ‘enchanted’) show house, pointing out the very latest in luxury features, beyond the dreams of Tom or Edith – Fairyland meets The Ideal Home Exhibition: central heating, which requires some explanation, fitted carpet, downstairs washbasin and lavatory, fitted cupboards and basins in the bedrooms, an electric stove in the kitchen, an ironing board and pastry board that drew out like drawers – Sherriff revels in the detail. And the house is fitted with a bell system, extending even into the bathroom! Even with all mod cons and a new fully equipped kitchen, a mortgage to pay and only a pension to live on, it would not occur to Mrs Baldwin (let alone Mr B.) to cook the supper or make the beds herself. If they are to move to the house of their dreams, a replacement for Ada would have be found.

The Baldwins have discovered the elusive mutual interest. Made in near despair, Edith’s imaginative suggestion of chasing past happiness along a familiar walk has planted the seed. Tom’s new vigour, and rebooted self-esteem brings it to fruition. Reversing the emasculation of retirement, he negotiates buying from a smooth and not entirely honest developer, and selling with the ‘help’ of a less than respectful estate agent, both familiar and brilliantly drawn characters, hovering between comic and mildly unpleasant. Sherriff’s sympathies lie largely with Edith, sweet, unassuming and long suffering, but he engages our sympathy with Tom in these encounters, as he discovers the difference between buying and selling: ‘When he had marched into a small, shabby Estate Office and announced in a crisp, authoritative voice: “We want to sell a house”, he had felt as though somebody had a opened a refrigerator door with one hand and cut the heels off his boots with the other. But when he had walked timidly into a palatial store and murmured: “We want to buy some furniture”, it seemed as if his heels were replaced with a deep bow and the whole building quivered with reverence.’

In coming so unexpectedly upon the Welden Close development, the Baldwins have found their shared retirement project. ‘This,’ says Tom, ‘is our place’. He finds himself almost physically drawn to the situation, to the plot itself, by an elm tree in the corner, ‘secretly beckoning to them with its delicate, lacy branch tips.’

This will be a garden he can nurture, and form, so different from the spent patch in Brondesbury, ‘sour, worn-out soil … beyond human aid and chemical manure.’ ‘Greengates’ will be the child they never had, the name chosen with the care and deliberation of young parents-to-be naming a son or daughter. Laying down his books on garden planning, Tom watches Edith sew, ‘Even with her spectacles on her nose and the pool of light shining upon her whitening hair she seemed like a girl-wife working with trembling and caressing eagerness upon the tiny clothes of a baby that would come to her in the spring.’ Edith thrills to the possibilities of a new home, into which she will breathe life and to which she will bring the finishing touches: new curtains, new weathered oak furniture, new cutlery, new linen, a new earthenware dinner service. ‘It occurred to [Tom] for the first time what a struggle poor Edith must have had to keep her love of freshness alive in the old house.’ At last, we feel.

It’s hard to believe that Greengates was written by a childless bachelor, who lived much of his life in his mother’s house. Sherriff’s fascination with domestic detail, including an improbable enthusiasm for the latest in kitchen appliances, bubble through, as does his delight in the comic minutiae of suburban life, the predictable characters, the roles allotted, the hierarchies so swiftly established in this new community. Underlying the social comedy, and not masked by it, is an astonishingly perceptive description of the strain placed on a marriage by retirement. Eighty years after it was first published, Greengates might usefully by placed on a reading list for couples facing retirement.