‘She had reached the Vauxhall Bridge Road now, and she turned back.’ Mary Heyham’s afternoon walk along Chelsea Embankment ends just across the river from Lambeth Walk where Amber Reeves assisted her mother, Maud Pember Reeves, in a remarkable piece of social investigation, initially published as a Fabian Tract and later expanded by Maud into the wonderful Round About a Pound a Week (Persephone Book No. 79), published in 1913 a year before A Lady and Her Husband.

Maud Pember Reeves had been a founder member of the Fabian Women’s Group in 1908, two years after her daughter founded the Cambridge University Fabian Society – Amber had been required by her father to choose between Cambridge and being presented at court. If there are elements of Amber Reeves in Mary Heyham’s daughter, the fictional Mary could hardly be more different from Amber’s mother, nor could her husband, James Heyham, be more different from Amber’s father, a radical politican who counted amongst his friends the Webbs , George Bernard Shaw and HG Wells, to whose child Amber gave birth (although she was by then married to fellow Fabian Rivers Blanco White) in 1909. The Lambeth Walk interviews may have laid the seeds, and the author’s Fabian beliefs are never far beneath the surface, however this is not an autobiographical novel.

Amber Reeves complained that her mother was too busy doing important things to look after her, a parenting model that she would follow in her turn, rarely seeing her children, who were cared for by a faithful old nurse (who refused to take a salary). Way ahead of their times, unopposed by their husbands, Maud and her daughter had broken the conventional mould. By contrast, Mary Heyham, the ‘lady’ of the title, engaged at seventeen, married at eighteen, ‘had kept her house and nursed her babies as she might have done a hundred, five hundred years ago’. For nearly thirty years her life has pivoted around her family. But the nest is emptying, the children are ‘going to other homes where she would be only a visitor who rang their door-bells and asked their servants whether they were in.’

Mrs Florence Moser by Jacob Kramer. Manchester Art Gallery.

Born and brought up in a prosperous Victorian household, Mary is facing middle-age in an era of change, under-educated and over-cosseted. Rosemary, her younger daughter, and favourite child, a thoroughly ‘new woman’, soon to be married, well-educated (Mary, interestingly, had seen to that), and an ardent socialist, accurately sums up her mother’s situation. She is ‘like an insect in a coral reef, ignorant of the laws by which she was governed’. Mathematics and economics were closed books, ‘philosophy meant that a great many cultivated people do not believe in God. Biology meant that in some indiscreet manner we are descended from monkeys.’ She had never seen a factory, nor entered the bank that sent her chequebooks; travel was a padded seat in a first class carriage. ‘Public opinion, since she was a rich woman, did not allow Mr Heyham to beat her or to take her money, and she could walk alone in the street without being insulted’, not the case for poor women. Mrs Heyham knew nothing of the lives of the women who served her, or who worked for the family business – a successful chain of up-market tea-shops.

With a remarkably mature understanding of her mother’s predicament, Rosemary, suggests she take up some sort of work among her father’s waitresses. Her older sister, preoccupied with early married life and pregnancy, agrees with ‘the easy enthusiasm of the irresponsible’ – Amber’s political pen is never far from her hand. Their brother Trent, oldest, least loved, least clever, and deeply conventional, takes a dim view, having had an upsetting encounter with a large waitress in Oxford, and afraid that Rosemary’s ‘confounded ideas’ will spoil his charming mother. James Heyham, who thinks of himself as ‘a modern husband, and a good one’, ‘a broad-minded man’ (James takes a very favourable view of himself in general), has no objection: ‘there were a lot of little things that might be done for the girls’, little being the operative word. It will be a new lease of life for ‘the old lady’, for ‘little mother’, for the ‘brave little woman’: he is, genuinely, fond of his wife, but there is no end to the condescending ways in which he addresses her, and about which, astonishingly, she does not protest. Mary has rarely protested, about anything, least of all about or to her husband.

Worried that she is not ‘as happy as she ought to be’ (‘ought’ is an interesting word), James encourages her, and Rosemary provides her with educational reading matter on women’s working conditions, and an assistant, the somewhat mysterious, assiduous note-taker, Miss Percival from whom over the months she will learn far more. Miss Percival has a keen eye for the petty injustices inflicted on the tea-shop girls, who must provide their own aprons, cuffs, caps and collars, and pay for their laundering, out of their paltry wage of 11 shillings a week, based on the unsubstantiated (and comfortable) belief that they were being supported at home, and subject to reduction for unpunctuality, and breakages. James Heyham has not built his fortune by being over-generous to his staff.

Mary’s first suggestions are modest: better shoes, chairs, somewhere for them to eat their meagre lunch, away from the wandering hands of the (male) cooks. James, though ‘he preferred to contemplate their trim waists and their clever manipulation of their hair’, agrees to the shoes: ‘… he would fix up with a firm that supplied ward shoes to nurses and see that the girls each bought a pair.’ Chairs and a safe place to sit meet with more resistance: ‘Do you imagine I pay them to be private and comfortable! I pay them to do my work!’ Mary, who had always thought her husband fair and just, wonders if she had been wrong, blaming herself for not having read the signs.

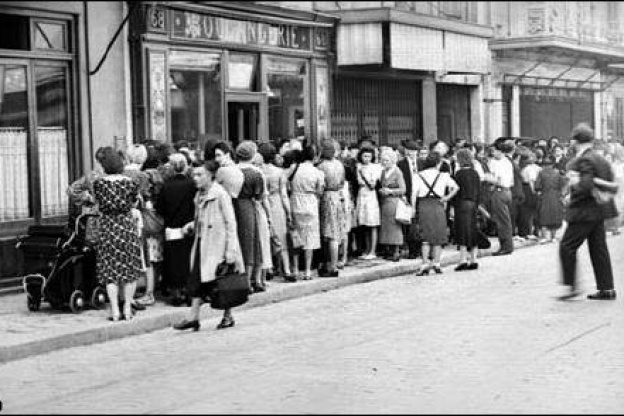

The scales finally fall from her eyes when she and Miss Percival visit one of the girls at home, a mean room with one bed shared with her dying mother, in Maida Hill, not Lambeth Walk, but with the same torn net curtain at the window and empty tins for decoration. Where Maud Pember Reeves painted the big picture, Amber focuses in on one individual: Florrie Wilson, unfairly sacked from the tea-room, as a consequence of being cruelly treated by a vengeful suitor, which ignites Mary’s social conscience. And it is Miss Percival, having offered immediate comfort to Mrs Wilson, and a refuge for Florrie, who strikes a spark of feminism in her employer with her first outburst, ‘it ought to be as safe for Florrie to have men friends as it is for your daughters. Only men, especially rich men, don’t want it to be.’ To be poor is bad enough but to be a woman and poor is unbearable.

Miss Percival’s rage is not so much with the politics, but with a society that, at every level, privileges men. Voicing Amber Reeves’s feminism she declares:

‘I hate them for what they’ve made of us … narrow, uneducated, trivial … If we’ve an instinct for order and organisation we use it to see that the cook keeps the kitchen clean, if we love beauty we embroider tea cosies or hunt in shops for pretty dresses, if we’ve more emotion in use than our man has an appetite for we’re allowed to work it off, sensibly and with moderation, in a religion he doesn’t take seriously.’

Girls, she says, are:

‘here in the world to please men, and most men wouldn’t know what to do with a really noble wife. So we lie to them, and tell them to mind their manners, and our clear bright eager little girls learn to chatter at tea parties … as they grow up something seems to go out of them. The pressure is too strong I suppose. They can’t stand up against what’s wanted of them.

James Heyham is one of those men. There is nothing exceptional about him. He considers himself to be both generous and honourable, and Mary recognises that other men would be unlikely to challenge that. He has been a good enough husband. He has been kind in his way, and loved her. Mary is shocked when she realises that after twenty-five years of marriage ‘James did not care first of all for her. He cared first for his work, for the business’, but he had never pretended otherwise. Charged with deceiving his wife, his angel in the house, he defends himself: ‘you have had your own standards, and you have simply taken it for granted that I should live up to them. … You may say that I deceived you, and that you have a right to know the truth. Well, I did conceal it from you, but my concealment was the price I paid for your immunity from contact with evil.’ Do we sense here a little sympathy for him? While favouring the ‘lady’, Amber Reeves does not shrink from presenting the case for ‘her husband’. Rosemary has seen his bad side, but finds him ‘much more enlightened and civilised than one has any right to expect from a father’. What damns James is his inability to change.

by John Singer Sargent.

Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco

Unsurprisingly he is dismayed to find his gentle submissive wife beginning to respond to the world ‘in an individual way’. Having initially approved of her interest in the welfare of ‘his’ waitresses, he is taken aback when, as half-owner of the business, a fact conveniently overlooked, ‘the old lady’ proves to have views on its future, a development he had not foreseen, and blames on Rosemary, ‘the tyrannous bluestocking’, whose subversive bookshelf Mary had fallen upon ‘with the enthusiasm of a girl of fifteen who is allowed at last to begin learning Greek.’ Having assiduously seen to the education of her daughter, she is able to reap the benefits.

As she sets out on the formative walk that takes her along the Thames to Vauxhall Bridge, Mary reflects on the evolution of women’s role and status through history, mirroring developments in agriculture, in industry, in economics: from the cave woman, holder of practical knowledge, to the head of the medieval household, responsible for apprentices, maids and labourers, and skilled in crafts, ‘spinning, weaving, preserving, baking – all the things that J and his friends were doing in factories.’ How much better, she reflects, for children too to live in such a community.

Mary is a complex and beautifully drawn character, whose belated, uneven, path to self-knowledge, and a sort of independence, is perfectly plotted, interwoven with fascinating minutiae of domestic life at a time of radical change for some, and resolute conservatism for others, and a picture of working life downstairs in the fashionable tea-rooms of the period, so vivid that Amber Reeves, the social researcher, must surely have observed it, if not actually carried the trays.