Setting her novel in the relative calm of a fashionable Italian lakeside resort in the early 1900s, an epoch she describes as ‘particularly loaded with femininity’, Gladys Huntington leads us to expect a tale of no more than mildly unhappy love affairs between never less than pretty women in elegant frocks and at least averagely good-looking and well-mannered men.

But Madame Solario is not an Edwardian novel, it is a hard-edged mid-twentieth century novel, boldly addressing a taboo area of female sexuality. We shouldn’t be surprised that Gladys Huntington, or her publishers, or both, opted for anonymity. Without suggesting that any of them might have been the “Anon” in the original publication, critics have compared her writing to Henry James, Edith Wharton, Elizabeth Bowen, Ivy Compton Burnett, while French critics have gone further, putting their money on Sybille Bedford, Françoise Sagan, and Winston Churchill as possible authors (the argument for Churchill being based on the mood of some watercolours of the South of France, and a scene in which the eponymous heroine draws linked Cs in the sand).

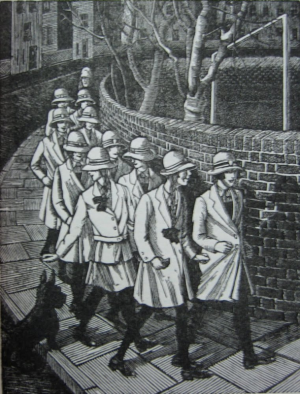

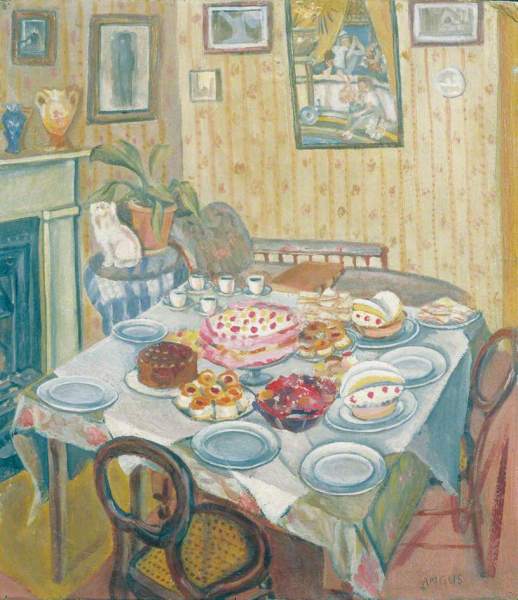

‘The evening steamer was just coming in, and everyone was out in front to see what new arrivals there might be. It was one of the events of the day, a social event, a “meeting’. Lake Como 1906. Though the head of the lake connected to all the capitals of Europe, Cadenabbia on the western shore could be reached only by water, a zig-zagging journey of ‘incredible slowness. Guests of the nearby Hotel Bellevue daily scrutinized the landing stage for fresh faces, new boating companions, fellow picnickers, dancing partners, and old friends. Lords, Ladies, Counts, Marchesas, and the occasional Princess mingled with the occasional Mr, Mrs, Miss or Colonel. A limited group of people gathered for a limited time – September was ‘the month’ earmarked in the social calendar – in a space limited by the length of one’s stride, oarsmanship, or a steamer timetable.

Into this almost classical setting, into this multi-national circle – English, Hungarian, Italian, American – Gladys Huntington places a young Englishman, an Oxford graduate, with little experience of the world, a Russian cavalry officer – a womanising gambler (possibly based on the father of Huntington’s adopted children) – and an outstanding beauty of uncertain nationality, with a scandalous past, and a limited moral compass, soon joined by an older brother, her near equal in looks, but far exceeding her in depravity. The beau monde unexpectedly meets a sinister, disruptive force.

His travelling companion having been taken ill in Switzerland, and quarantined for a month, Bernard Middleton, the young innocent, finds himself unexpectedly alone in Cadenabbia. Shy, but opinionated and quick to leap to conclusions, Bernard’s is the voice of the first and third parts of the novel. We see only what he sees, and he is a man of little imagination, and limited emotional intelligence. Huntington evokes his turn of phrase brilliantly and with humour, as he takes his first steps among his fellow guests at Hotel Bellevue, introduced to him, and to us, by the avuncular Colonel Ross, who ‘was as cheerful as if he were to be personally congratulated on all the good points of the place and its society.’

We could be reading Bernard’s diary entries, or letters home, as he describes a middle aged woman ‘who had a stony face and talked in accurate French to several people who sat with her in a corner of the hall. She might be important but she was not French.’ Or others who ‘spoke English to each other, but were certainly not English.’ He takes against the Russian roué, Kovanski, on sight, ‘his prominent eyes had a disagreeable stare, and he knew at once that he did not like the man or the stare.’ He knows very little of young women, particularly young foreign women, but confidently notes of Hungarian Ilona, ‘one could see at once that she was unhappy’. His manner is inept, but Bernard is ‘a very pleasant-looking young man, of a good height [always important], with reddish hair’ and has a very nice smile. The girls, ‘even the Americans’ seem to like him. ‘It had been taken for granted that, being English, he was what they called “timid”.’ Middleton, as they, being modern young women, call him, is quickly swept up into a whirl of boat trips, and excursions. Had it not been for Madame Solario his month by the lake might have been a gentle rite of passage, a safe awakening of first young love.

Hoping to find Ilona, Bernard eavesdrops on a conversation between her mother and the Colonel: ‘“Madame Solario is coming back tomorrow”. “Ah, vraiment?” Countess Zapponyi replied a little sharply.’ Clearly both the Colonel and the Countess are acquainted with Madame Solario, the Countess evidently having some reservations; but the name overheard from behind a column, as yet, means nothing to Bernard.

Hints and whispers and snippets of gossip slowly coalesce like pieces of a blurred jigsaw, several missing, or blank. The picture we have of Madame Solario is as gossamer thin and shifting as her tulle wraps, or her underlayered lace dresses. We don’t learn where she is coming backfrom, nor what she has been doing: asked if she has had ‘an amusing time’, she replies simply “Yes, thank you.” Is she English, American, South American, Swedish perhaps? Once again Bernard is clear: ‘One could tell at once that she was English-speaking by birth, but yet there was at times a faintly un-English flavour to her speech that pointed to the probability that she had lived most of her life abroad.’ As for her age? ‘She was not a girl, not young in his sense, though he knew she could not be more than twenty-seven or eight …’ asserts Bernard. We can’t be sure .

The only certainty is her startling beauty: fair, ‘a little above medium height’; ‘there was a softness in everything she did, and even the prosaic act of eating was invested with grace.’ A rare authorial intervention adds a period detail that would have escaped young Middleton,

‘In those days the great, equalising power of cosmetics and beautifying inventions had not yet been let loose, and Madame S’s complexion and colouring, and the arc of her eyebrows, and the wave of her hair (that morning under a hat made up entirely of crisp, pleated frills of lilac muslin) were not being counterfeited by everyone who wished; they were rare, like noble birth. The high rank of her beauty had to be met with something of awe.’

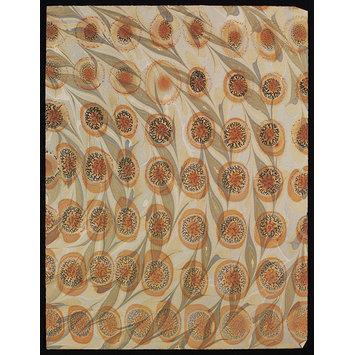

The hat of course is another period piece, and Madame Solario has one for every occasion. Seen first in ‘a hat trimmed with velvet pansies in shades of mauve that deepened into purple’, then in ‘a large white hat – what was called a restaurant hat – [a restaurant hat?] – with a transparent brim and a huge pink rose in front’, for boating ‘a hat of natural straw’, for travelling ‘a small blue hat that had a pair of birds wings for trimming’ and a large hat-box one assumes.

Her hats are the brightest pieces in the puzzle, in stark contrast to her favoured choice of white for her dresses and blue for her shawls, not by accident surely, the traditional colours of the Virgin Mary. There is nothing about Natalia Solario that is not planned, even the softness that so impresses Bernard. Boating on the lake, he takes the oars, but Natalia – or is it Ellen, or Nelly, even her name is uncertain – takes up the steering ropes, ‘ “I shall steer”, she said, with a pleased look …”’

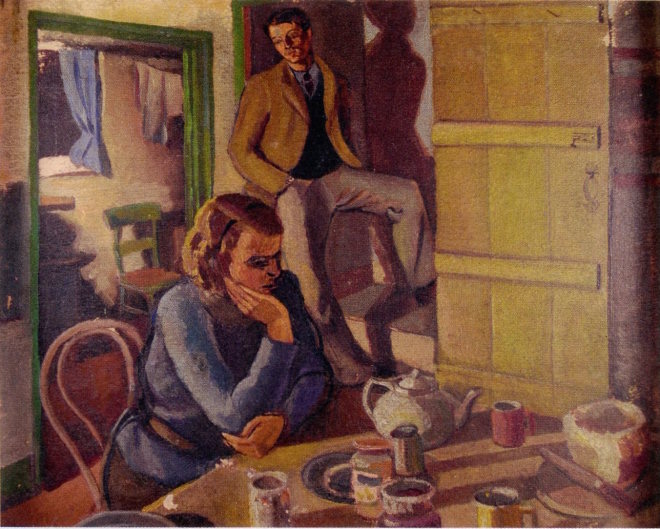

The boating trip is not the bonding experience that he had dreamt of. Unhappily, aware of the fact that she does not share his feelings, he realises ‘that she was as good as alone in the rowboat, and that in his youth and shyness she found simply an absence, welcome for the time, of the attentions that pursued her.’ Quite perceptive, but far from the whole story. Madame Solario is using him in ways that he cannot begin to understand. She has whitewashed out the scandal of her past – that her stepfather was in love with her (so delicately phrased), when she was not yet sixteen and her older brother, Eugène, effectively disappeared after attempting to murder him. As the French gossip who eagerly reveals all puts it ‘tout est comme si rien n’était ni ne fut’. Bernard, unsurprisingly, doesn’t believe a word of it.

Reading Madame Solario I was reminded of lines from Josephine Hart’s 1991 novel Damage,‘Damaged people are dangerous. They know they can survive.’ Madame Solario has survived. Her brother has survived more: the loss of his father, the shame of his mother’s humiliation by his step-father, her death, his exile, poverty. In what may be the final throw of the dice, he arrives in Cabenaddia, having spent the last of his funds on new clothes, and new luggage, ready, with the connivance of his sister, to get what he can from the comfortably moneyed clientèle of the Bellevue. ‘The social life of the hotel was a forcing-house for situations; the opportunities to see, meet, succeed, fail, and recover never stopped from morning till night.’ Together Eugene and Natalia, brother and sister, make a handsome couple, a dazzling pair, opportunistic chancers without a scruple between them, ready to make use of, or, if necessary destroy, anyone who comes within their orbit: the name Solario says it all. With masterly sleight of hand Gladys Huntington draws her readers into the charmed circle. It is hard to dislike these monstrous characters.

Eugene is the more damaged, the more dangerous, Natalia softly complicit. And Bernard is both victim and unwitting enabler of their eventual flight. Blithely over confident, he has ignored Colonel Ross’s kindly advice to be careful with foreigners, ‘we don’t quite understand them – they don’t play to the same rules you know’, and is baffled by the warning he receives from a wise Milanese doctor to ‘get on to solid ground as soon as you can’.

“… you may know that geologists speak of faults when they mean weaknesses in the crust of the earth that cause earthquakes and subsidences.”

Having pulled on his gloves he was energetically buttoning them.

“And I will tell you something out of my own experience. There are people like ‘faults’, who are a weakness in the fabric of society; there is disturbance and disaster wherever they are.”

Bernard can think only of mountain climbing and crevasses, not of his adored Madame Solario, and her equivocal brother.His month by the lake has taught him nothing. Madame Solario is no ‘bildungsroman’. He is blind to their machinations, and naïvely, ignorantly, unaware of the nature of their relationship. By way of a footnote, the French translation is more explicit than the original: ‘the stress he was under was so great’ is rendered as ‘la violence du désir’. Huntington frequently wrote diary entries in French. She must have known.