When Mollie Panter-Downes died in 1997 at the age of 90, the New York Times obituary writer concluded that, ‘For all her literary output, she was something close to a typical country housewife, one who did her own shopping, cooking and canning’. Canning? What do they know at the New York Times about the typical English housewife, which, incidentally, she most certainly was not? Mollie Panter-Downes contributed an astonishing 852 pieces to the New Yorker between 1938 and 1986, poetry, reviews, a regular ‘Letter from London’, and thirty-six short stories. The New Yorker described her as ‘bred in the bone English’, ‘every American’s English cousin’, but one wonders if a little of the exquisitely fine detail of her descriptions of English middle and upper-middle class life was not occasionally lost in translation. Bottling not canning was the English way, before, during and for some time after the Second World War. A detail, but Mollie Panter-Downes had 20/20 vision for detail, just as her ear was perfectly tuned to the voices and turns of phrase of her milieu.

To read Good Evening, Mrs Craven: The Wartime Stories of Mollie Panter-Downes is to look at domestic life in wartime England, or more precisely, wartime Home Counties, through a lens tightly focused, often, but not always, kindly, on the everyday. Beginning on 14th October 1939 and ending on 16thDecember 1944, the twenty-one stories, vignettes of the ordinary, containing no heroics, little drama and few deaths, reflect in their deliberately small way, the course of the war. The titles say it all: the first, ‘Date With Romance’, a doomed, but amusing, lunchtime meeting of old flames in the still unthreatening period of the Phoney War; the last, ‘The Waste of it All’, a marriage sadly tested far too early by wartime separation. Reading these stories sixty years on, we know about the course of the war. We know that the Phoney War would come to a brutal end in May 1940, and we know too that hostilities would drag on for months after December 1944, and that many marriages would be among the unlisted casualties.

There is a peculiar poignancy in reading these stories, knowing not only more than the characters, but more than the writer. To those concerned that their unwelcome guests, be they evacuees, or one-time friends, will be with them for the uncertain period of the Duration, we could offer some comfort: it will be over by 1945. We might warn those who know someone, who knows a man in the War Office who says the Germans are not going to send over many raids, not to be so sure. Mrs Peters tells Mrs Ramsay’s sewing party that, according to Mr Peters, ‘if the Americans came over and fought, we’d have the Nasties beaten before the end of the year’. We know from the date, 8th March 1941, that indeed it won’t be long before they come over, but it will be a long time before they get the Nasties beaten.

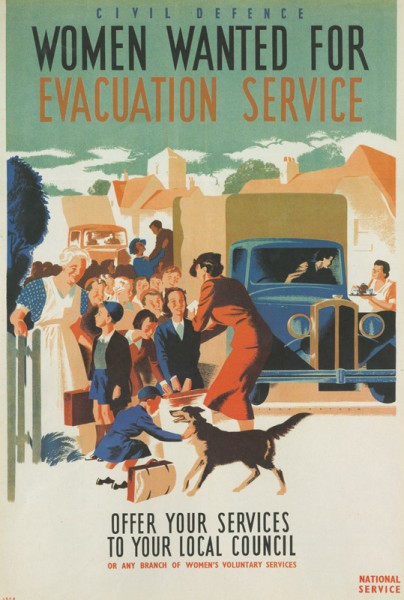

They cannot know what will happen in the future, and they have only the barest cognisance of what is happening beyond their own parish boundaries. Their war is on the home-front, and, if there is another front, it is a long way off, talked of on the wireless, and mentioned, but not dwelt on, in letters, which women read, or in newspapers which men read and keep to themselves. On the home front a few veterans of the First World War prepare eagerly to do their bit as air raid wardens, and some men, too old yet to be called up, have desk jobs in town, but most of the ‘Staff Officers’ now are women, and apart from a few over-age rheumatic gardeners, lame schoolmasters, or under-age paperboys, so are most of the Other Ranks. It is a woman’s world, in which even the food has been adapted to female tastes and appetites, served in portions small enough to sit on trays.

There are older widows in the big houses, young married women in pretty cottages, women who clean or cook for them, in humbler village dwellings, spinsters in small town flats or bedsitters. Mollie Panter-Downes looks with wry amusement at the power struggles fought across these domestic battle fields. The big class battle that will result in major social change rumbles far below the surface but there are small regular skirmishes.The calm of a sewing bee, briefly threatened by a trivial quarrel, is restored when conversation turns to hens and gooseberry jam. The tottering balance of a lunch party is saved by the timely sounding of an air raid siren.

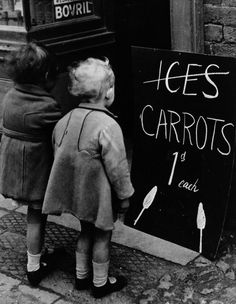

Far bigger struggles develop when the uninvited guests, or erstwhile friends, or, most problematic of all, evacuees, move in. This is enemy occupation in the home. Goodwill is tested to the limits. Tiresome Mrs Parmenter unhelpfully picks flowers, but never makes a bed, while her reluctant hostess pictures life twenty years on, her baby a grown woman, and Mrs Parmenter running out between the showers to pick roses for her wedding bouquet. Young Mrs Fletcher is disappointed by her evacuees: ‘it was natural they should look dingy, but she had imagined a medium dinginess that would wear off after one or two good scrubbings and a generous handout of gingham pinafores’. We hear her inner voice wishing that their needs ‘might all simplify down to something which could be settled by the stroke of a pen on a cheque’.

We can imagine ourselves in these situations, and know that our patience too would fail us, that our desire to do good would not be equal to the overwhelming desire to have our home back, tidy, clean and ours. We would do no better than Mrs Ramsay, or Mrs Fletcher, or even, perish the thought, than Mrs Parmenter. And so we can laugh at Mollie Panter-Downes’ descriptions. We are not mocking, it could be us. Nor can we cannot forget that the dreadful Mrs Parmenter, and the friends who have outstayed their welcome, and the evacuees, and Miss Mildred Ewing who drags her long-suffering maid from hotel to hotel, and thin Rachel Craig, with no hat and ‘a very good baby’, had homes once, where they would far rather be, but which may not be there when their exile ends.

Don Merrill is a painter, his wife an interior designer: now that London is filled with the fine brick dust of bombed out houses, they are redundant. What use is a decorator when there is nothing to decorate? ‘Even if people had the money to spare, they didn’t want to spend it on things which, experience had shown, were subject to splintering and mangling. The War Time Stories say little directly about the real and devastating splintering and mangling, taking place beyond the fiercely defended rural citadels. When the gunfire begins in earnest across the Channel, it is the shivering of the Palm Court windows, and the slopping of the China tea in the trembling saucer that make it real for Miss Ewing and the ladies in the San Remo hotel, Crumpington-on-Sea.

War makes people selfish. When food is short, you hide the chocolate. When fuel is short you hog the fire. Interrupted monologues replace conversation. People talk ‘only of themselves, their jobs, their bombs…’. Mrs Bristow’s concern is for her own children, ‘small and stranded and precious, in California’. How can she share her cook’s anxiety for her daughter in Singapore? When, like the Merrills, what you want is a party, the lack of available friends can make you angry and sad, and not always in equal measure. War generates a heartless practicality.

War can be absurd, and war can be fun. It can relieve the tedium of a humdrum life, it can give purpose to an aimless existence, solace and companionship to the lonely faced with the knotty problem of making sterile dressings in an unsterile drawing room, for as yet unwounded soldiers. The Pringle sisters are happy, ‘happier, as a matter of fact, than they had been for the last twenty-one years.’ Miss Birch will not find again the friendliness and warmth that she enjoyed with her neighbours during the terrible nights of the blitz. War can provide a square meal. The penniless painter, Don Merrill, enlists for the money. War is dangerously attractive. Reading of the death of his friend, Travers, Mark Goring is surprised to feel a pang of envy. The prospect of a posting to Delhi leaves him ‘hugging the thought that danger was as possible for him after all as it was for Nigel Travers or the next man’.

Mollie Panter-Downes paints sadness but she doesn’t paint tragedy – death and destruction happen at a distance. She picks out the courage, the stalwartness and the weaknesses of women, and a few men, with a fine brush and a light touch, preferring laughter to tears. Most of her characters are survivors, but they face an uncertain future. As the war and The War Time Stories draw towards a close, it is clear that her premonition voiced in 1940 was correct: things would never be the same again, ‘something of the Clarks [Mrs Fletcher’s troublesome evacuees] would be there forever’. The old retainers will die and no young retainers will take their place. Some like Janet Goring will fight against change, continuing to turn down the bed and lay out the pyjamas ‘as though another had done it’. When the elderly Mrs Walsingham welcomes a number of companionable, but not overly respectful, Canadian soldiers into her house, her loyal maid continues to believe that ‘things were just as they used to be, that their world which had come to an end could still be saved’. But trees must be chopped down to make space for military equipment , and ‘To tell the truth’ says Mrs Walsingham, ‘I think it’s an improvement – lets in more light and air’. Change is coming, and, like Mollie Panter-Downes she recognises that the bright side is the one to look at.

Questions

At The New Yorker, Mollie Panter-Downes was thought of ‘as bred in the bone English’. Do you feel that she tailored her stories to an American idea of Englishness?

Houses play a very important part in these stories. In what ways are they more than ‘bricks and mortar’?

Examples of Mollie Panter-Downes humour are too many to list and, like so much humour, hard to analyse. What makes so much of her writing comic? Is it ever cruel, and, if it is, does that make it less funny?