The title is Julian Grenfell, His life and the times of his death, 1888-1915, but Nicholas Mosley, in his preface to the Persephone edition, readily admits that his book is as much, if not more, about his mother than it is about Julian. ‘We did have fun didn’t we?’, perhaps the saddest words in Nicholas Mosely’s moving and complex biography of Julian Grenfell, come from his mother’s obituary. Ettie Grenfell, Lady Desborough, had lived her whole life by, what Cynthia Asquith, the daughter of her great friend, Mary Elcho, dubbed her ‘stubborn gospel of joy’. Those close to her had been required to live by it too, or, if they could not live by it, to pay full lip service to it.

Julian’s personal tragedy was not so much his early death, one, after all, among millions, but his life, and that was, for the most part, determined by his mother. When her son rebelled, she chose to ‘back her ideals’. Mosley argues that this was not inevitable, but the fact is that her life depended on those ideals. That was her tragedy. It was those ideals, social attitudes of her times, honed in her own exceptional way, that enabled her to pass through life without looking back into the darkness behind, or down into the abyss.

In matters of grief Ettie’s lessons started early. When she was only a year old she lost her mother, at two her father and at eight her brother. At thirteen she lost the grandmother she loved best. Recording these losses seventy years later, she wrote of ‘the wretched embarrassment of a child in grief; the shame of tears’. Life was terrifyingly unpredictable but she had learned that while it might not be possible to control events – although in that regard she would do her damndest – , it should be possible to control the show of emotion, and the events themselves could always be rewritten, ‘everything, regardless of appearances, must be for the best, because to suppose otherwise would be unbearable’.

Ettie may have been self taught in cheerfulness, but the doctrine was one which she made sure was instilled into her own children at a young age. Julian was 2 ½ when his Nanny wrote to his parents, in India for several months, ‘Julian is really a changed child, he never cries about anything’. Later his letters from his preparatory school would be ‘consistent in their assurances of happiness’. In his first letters from Eton he writes ‘I am very well’, ‘I like it awfully’.

‘It would have been difficult to write anything different’, notes Mosley, (from the heart, one senses), ‘and to be approved’. His letters to his mother from Eton record marks gained, runs scored, goals won.

As he nears the end of his schooldays, Julian has become so adept at cheerfulness that he is teaching it. Writing to Ettie on the death of their old Nanny, he urges ‘surely the great maxim is to take everything and especially death, in the most natural and cheerful way that we possibly can, without letting ourselves be absorbed for one instant in the little petty things or forgetting the great mysterious background that there is to everything.’ Even on his own death-bed, he was able to appear cheerful, so much so that the doctors did not at first realise how ill he was. His mother in her account of his last days affirms ‘The thought that he was dying seemed to go and come but he always seemed radiantly happy…’ . Ettie’s words bizarrely echo Julian’s own, in a letter to his sister six years earlier, about the death of their mother’s young lover, ‘she is happy about it all, radiantly happy’.

That Julian should write to his sister about their mother’s grief at the death of Archie Gordon, is no less surprising than the fact, unseemly to modern readers, that both his sister, the fifteen year old Monica, and his brother Billy should have written her letters of condolence. Julian also wrote, apologising for not being able to help her. The reason he couldn’t even begin to help, was that he was in the middle of what was clearly a nervous breakdown. ‘I feel as if I had been smashed up into little bits and put together again very badly with half the bits missing’, was how he described it to Marjorie Manners, with whom he was in love at the time. He had risked writing to his mother about his mental state, ‘I’ve tried your system of playing up, but miserably badly’. For Ettie, it was another problem to be swept under the carpet. When Archie Gordon’s successor, Patrick Shaw-Stewart, Julian’s friend and Oxford contemporary, wrote asking after him, Ettie replied ‘Juju isn’t a bit better, but we won’t go into that.’

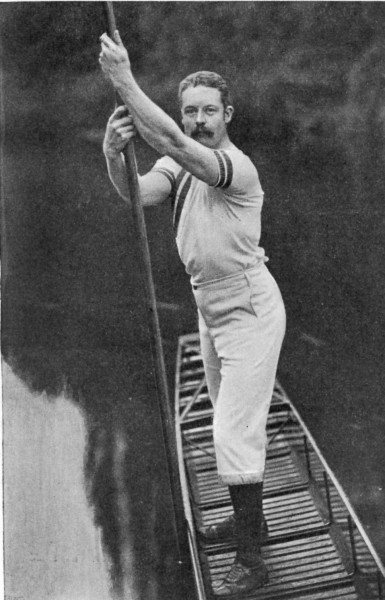

And yet by the standards of the times, Ettie Grenfell was not a bad mother, any more than she was a bad wife. Married in 1887 at the age of 19 to Willy Grenfell, twelve years her senior, MP, outstanding sportsman and committee member, she had produced the required ‘heir and a spare’ by 1890. For a young woman, rich and beautiful, marriage in the 1890s meant freedom, not constraint. She was known as a model wife, a reputation that she guarded fiercely, he as a model Englishman, but ‘Willy was a conventional man, and lovers were conventionally acceptable if not too much about them was known’. In 1891 it was fashionable for a young married woman to have lovers and Ettie followed the fashion. The ‘rules of engagement’ were pretty clearly demarcated – ‘romance and passion, if they were to co-exist with ideas of fidelity and duty, had to remain largely in the mind’ – and Ettie’s rules were, predictably, exacting. There was a pattern to her ‘affairs’ : ecstasy, dependence, loss, anguish, repentance, reassurance, ecstasy. It was cyclical and predictable.

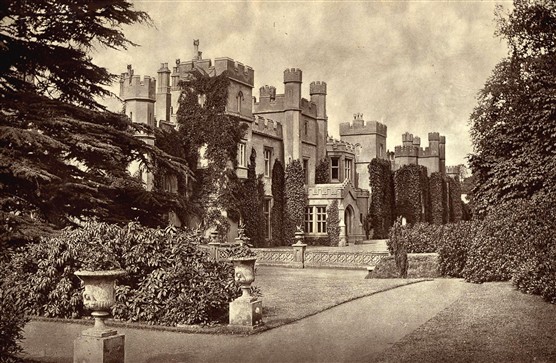

The circle in which these fantasies were played out was a small and exclusive one whose members came from a few, extended and interlinked aristocratic families. Charteris, Wyndham, Asquith, Grenfell, Horner, Tennant – husbands, wives, lovers, friends were chosen and exchanged largely within a group of like-minded men and women, who came to be known as the Souls, a name coined for them by Lord Charles Beresford in 1888, because ‘you all sit and talk about each other’s souls’. The name is misleading in suggesting both personal intimacy and lofty intellectualism. The women may have enjoyed intimate friendships, but the men were happier on a horse, or with a gun in their hands. Together their delight was in games, word games, charades, guessing games, games in which wit was valued as highly as erudition. Dinners, balls, weekends, hunting, shooting, and for the men politics, for they had their serious sides, made for a hectic round which left no time for boredom, nor for close inspection of the vacuity of their lives.

Children found what space they could in the dizzy social and sporting whirl of their parents. Often away for weeks, or months at a time, Ettie, sometimes with Willy, would descend, from time to time, like a goddess, on the nursery. For a few precious weeks she would be the perfect mother, spending more time with her children than was usual among her contemporaries. Together they climbed trees, played hide and seek, clambered over rocks. In the summer she would take them away, enjoying playing at the simple life with them. In her own way, and perhaps as far as she was able, she minded about them. When it was time for Julian to go away to school, she took him to look at three schools before deciding on Summerfields. She wanted him to be happy. She wanted it so much that she was blind, deliberately blind, to his unhappiness even at this young age. With heartless pride she described his first journey to school, ‘His fighting spirit leapt to the adventure, and he did not shed one tear, but he was sick several times on the journey from Taplow to Oxford.’

The messages were confusing. Love was given, then inexplicably and abruptly withdrawn. The same cycle of adoration followed by guilt, humiliation and ecstasy, that we saw in Ettie’s relationship with her lovers, who by the time Julian reached his last years at Eton were closer in age to him than they were to her, was repeated with her son. It is not surprising to find Julian writing ‘I can’t understand love’, ‘…this faculty of affectionateness has been left altogether out of my composition. I really believe this; things people say and do, and things in books, often seem incomprehensible to me’.

Pleasing his mother became even more difficult after Eton, when the weekly offerings of good marks, and runs scored inevitably ceased. ‘You implore me not to live the solitary life, and die of mortification directly I like anybody’, ‘You implore me to work, and cry if I don’t dance nightly’. Finally, and with great courage, he rebelled. In 1909, while still at Oxford, Julian wrote a short book of essays, which were nothing less than an attack on everything that his mother lived by and for. In it he exposed the contradictory ideals with which he had been brought up, and which he was convinced would lead to a collective schizophrenia. He believed that society was beginning to search for a ‘competitive self-sacrifice just to prove itself not ludicrous’. But Ettie hated the book, and it marked the start of a long period of (intermittent – for nothing in Ettie’s life was ever consistent) conflict between them.

Ettie’s reserve in personal matters mean that we know little of her state of mind during this time, but one might wonder if she wasn’t going through an uncomfortable period of her own. She had reached her mid-forties, youth was behind her, her husband was loyal and trustworthy but hardly a fellow soul (small ‘s’). The heavy jawed man we see in the photograph with his family, whose idea of a suitable exhibit for the 1910 International Exhibition in Vienna was a room hung with animals’ heads, does not give the appearance of an enjoyable drawing room companion.

Four years later Europe would be at war and everything could fall into place, just as Julian had predicted. The upper classes knew what they had to do. The men had been steeped in classical literature throughout their years at school, and university. They had been brought up believing that war was a way by which a man could ‘prove’ himself. War offered the chance of achieving glory, alive or dead. The women could prove themselves like the women of Sparta by giving up their sons ‘with anguish unrevealed/By eyes o’erbright and lips to laughter lent’, in the words of Arthur Jenkins. Ettie could write to her daughter Monica when Julian left for France of ‘the anguish of this, and yet the uplift’.

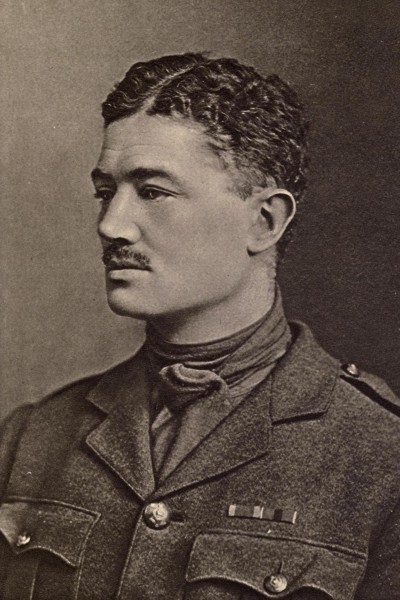

Julian had joined the army after Oxford, partly to escape his mother’s wrath and certainly to get away from England. He had no illusions about war, but seems genuinely to have loved it. After India and South Africa, France was the real thing. ‘I’ve never been so fit or nearly so happy in my life before. I adore the fighting … I adore war’, he wrote to his mother.

Julian died from a head wound on 27th May 1915, with his parents and Monica at his side. His brother Billy had arrived in France a week before. ‘I’m glad there was no gap’, said Julian. Billy would be killed on 30th July. The Souls had met less and less after 1900, but they would come together, not so much to grieve but to delight in their losses. In 1918 Ettie wrote to Mary Wemyss (Charteris) who had lost two sons, ‘As these agonising days go on, one can feel almost glad that Ego and Ivo and Julian and Billy are safe in the dream of peace.’

In 1926 Ettie offered up her third and last son, not for her country this time, but to a motor accident. ‘We did have fun didn’t we?’ no wonder that plaintive question mark hangs there.

Questions

Is it fair, or even possible, to judge them from our own viewpoint, informed by twentieth century psychoanalytical theories and notions of child rearing? Could Ettie have been a better mother?

If there was a collective death-wish driving Europe towards war, can it be explained? Is it conceivable that it could happen again?

Why is it so hard to accept Julian’s enthusiasm for war? Do we think less of him?

A Footnote

Julian Grenfell was born on 30th March 1888 at 4 St James’s Square, near Picadilly. The house belonged to his great aunt, Katie Cowper, who shared in Ettie’s upbringing after the death of her parents.

From 1912 to 1942 the house was owned and occupied by the second Viscount Astor. Nancy Astor was the first woman to sit as a Member of Parliament in 1919. In 1942 it was requisitioned by the government and was used as the London headquarters of the Free French Forces. In September 1947 it became the home of the Arts Council of Great Britain. Subsequently, the building was used as a Court House for several years, first as a division of the High Court, then as a Criminal Court, then as the Employment Appeals Tribunal. Finally in 1996, the house was purchased and became the property and new home of the Naval & Military Club otherwise known as the ‘In and Out’.

To find out more go to http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=40548