Who could not enjoy Delafield’s self-deprecating humour and lightly satirical tone? It was hugely successful when it was published in 1930, and remains her best known book. But her own favourite was Consequences. There are a few brilliant examples of Delafield’s cutting wit, but it is a terribly sad book. For fans of E.M. Delafield’s best known novel, Diary of a Provincial Lady, it is useful to think of it as the last of a quartet covering roughly forty years: Consequences, Thank Heaven Fasting, The Way Things Are, and Provincial Lady. The heroines (or perhaps anti-heroines) – to take them in order, Alex, Monica, Laura and the eponymous Provincial Lady – are all caught in a system which favours men and in which women must find their place. Alex is broken by the system; Monica survives, not unhappily, by adapting to it; Laura forces herself to adapt, unhappily, and PL survives thanks to a sense of humour and a good circle of women friends.

Consequences is an extraordinarily rich novel tightly focused on its main character, and trapped in its period, and its social milieu, yet touching perceptively on a wide number of themes, very occasionally with a certain wry humour, society, men and women, family, friendship, expectations and disappointments, fate. E.M.Delafield shows in agonising detail how cruel life could (and can) prove for the misfit, and the rules and customs of late Victorian society were as tight and constraining as the corsets into which its women were laced.

The rules of this Victorian parlour game include a note that ‘the person who began the story by writing a man’s name gets to keep the story.’ A footnote, but one that sheds a chilly light on the patterns ingrained in the Victorian nursery. The story belonged to the men. A woman alone was socially, and economically marginalised.

But few young girls in the upper echelons of Victorian society needed a game to remind them of that. Their upbringing, education and social life were meticulously managed to ensure a good marriage. The window of opportunity for achieving this was small. A girl would ‘come out’ at seventeen or eighteen, and would have one, two or, in the most desperate cases, three ‘seasons’ in which to meet not Mr Right, that would be a bonus, but Mr Socially Acceptable and Financially Secure. An attractive girl, blessed with self-confidence might dance her way swiftly to the altar. Her more awkward, plain, shy, or simply immature sisters could find themselves not just alone, but destroyed by the system.

To her mother’s chagrin, E.M.D had been one of the ‘failures’, and knew the pain from her own experience. Harsh as the system was in 1908 when she came out, it was a little gentler than in the 1890s when she sets her novel, in no small measure thanks to Freud, and advances in understanding the influence of childhood on the development of personality.

We meet the Clare children, Alex, Barbara, Cedric, Archie and Baby Pamela in the nursery of their Bayswater house. Barbara is angry and sharp-faced, but nevertheless favoured by Nurse; Cedric is judicious and dignified, and doesn’t give a fig for Nurse’s opinion. Alex is proud and dictatorial, and disliked by Nurse, who considers her violent and overbearing. As the eldest, she is sometimes allowed to join her mother’s friends in the drawing-room, a privilege which she mistakenly believes to be a sign that she is her mother’s favourite. The sad truth about Alex is that she is nobody’s favourite. Indeed nobody seems to like her much, not her mother, nor her siblings, not Nurse, not the nursery maid, who refers to her as the ‘drawing-room child’. Even E.M.D. seems not to like her. She implicitly acknowledges, and understands her pain, but allows her few redeeming features. Alex is disagreeable, and mean-spirited. The novel is largely written in her voice, exposing her self-centredness, her neediness coupled with limited awareness of the needs of others, her lack of moral compass, her lack of energy, her impulsiveness and her immaturity. Alex is not loveable. But poor Alex has never been loved.

Asked the secret of a successful marriage, Judith Viorst (see the Forum about It’s Hard to be Hip) replied ‘dumb luck plus a huge amount of hard work and a willingness to laugh’, a good formula for life itself. Alex at first does not accept the necessity for hard work, then later lacks the strength for it. Her sister when they are both grown up suggests that she might be happier if she would only cultivate a sense of humour. Indeed she would. But, like many self-centred people she is unable to laugh, and as time goes on has precious little to laugh about. Worse still, she has no luck.

Her first misfortune is to have been born a girl. Like all Victorian upper class parents Sir Francis Clare and Lady Isabel would have wanted their first-born to be a boy. Even after the longed for sons arrive, her father finds his daughters unsatisfactory – Barbara shows plenty of verve but is plain, while Alex is pretty but lacks all gaiety. ‘It was only in his two sons – Cedric, with his sort of steady brilliance, and idle happy-go-lucky Archie, by far the best-looking of the Clare children – that Sir Francis found unalloyed satisfaction.’ Unalloyed love is what every child needs. Her mother is dazzling and hard as the rings Alex is allowed to watch her put on, in a pathetic little moment of intimacy, before she hurries off to dinner. Her father is a distant figure who abhors all show of emotion. With increasing desperation, Alex will look elsewhere for the love she lacked as a child.

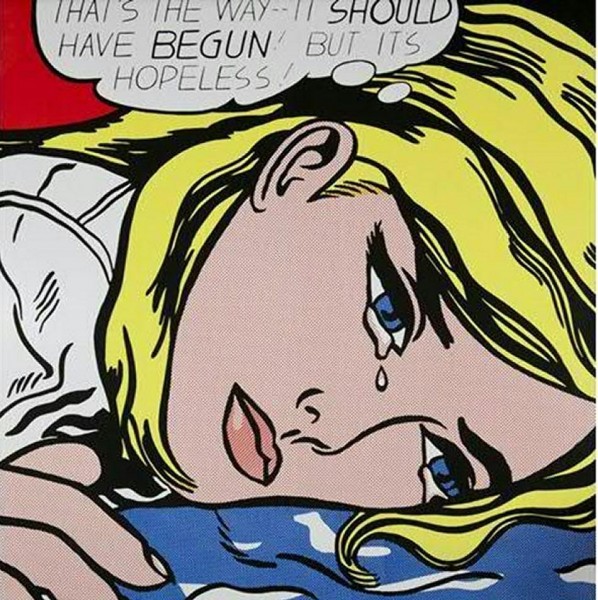

A moment of bad luck sets in train a chain of events which alters the course of her life. A childish prank goes horribly wrong. Impulsive, dictatorial Alex, forces her sister to walk an improvised tightrope. Barbara falls and injures her back. She must be cared for. No-one thinks that Alex might need a little reassurance. Her punishment is to be sent away to a convent school in Belgium. ‘And that,’ writes Delafield, ‘was her first practical experience of the game of consequences, as played by the freakish hand of fate.’ From the age of twelve, Alex feels herself dogged by destiny, ‘eternally different from her companions, eternally destined to lose her way.’ Much later, as she struggles through her second season, she wonders ‘drearily [what a sad, lowering, and brilliantly chosen adverb] if she was always destined to find herself out of all harmony with her surroundings. She never questioned but that the fault lay entirely in herself, and a sort of fatalism made her accept it all with apathetic matter-of-factness.’ The voice here, unusually, is Delafield’s: can one detect a hint of irritation?

‘Friendly with all, familiar with none’ is Sir Francis’ parting advice to his twelve-year-old daughter as she leaves for Liège. How, with so little experience of friendship, or familiarity, could she be expected to understand? E.M.D., aware of the burgeoning study of human psychology, explains what Sir Francis, left emotionally illiterate by his own Victorian upbringing cannot (Alex later recalls ‘the frozen rigidity of her father’s anguish’ after Lady Isobel’s death). ‘Nothing but the most exclusive and inordinate of attachments lay within the scope of Alex’s emotional capacities. She was incapable alike of asking or bestowing in moderation.’ Arriving at the convent, she is drawn to a young schoolmistress. E.M.D.’s assessment is expressed in clear Freudian language: ‘one of those violent attractions for one of her own sex, that are apt to avail feminine adolescence.’ The tall Belgian postulante who polishes the floors, then Marie-Angèle, an older French girl, and most powerful, the magnetic, precociously self-confident, calculating Queenie – Alex throws herself into a series of pashes, to use the now outdated schoolgirl parlance.

Mutual friendship, on equal terms, is not within Alex’s emotional range. Her relationships are overwhelmingly one-sided. Indeed she shows little interest or curiosity about those from whom she expects so much. E.M.D. seems to be saying, perhaps reflecting her own unhappy childhood, that having been denied a mother’s love, always seeking for a substitute, she is unable to move on to a mature relationship.

Having failed to form friendships at school, Alex pins her hopes on her first season. ‘Everything she had longed for, and utterly missed throughout her schooldays would now be hers.’ She never doubts that in a long dress and with piled-up hair, she will attract the same admiration that she enjoyed as a child in her mother’s drawing-room. Nor does she doubt that marriage will follow. Blind confidence, lack of self-awareness and a disastrous anxiety to be liked form a cruel combination. With an irony, rare in Consequences, but so characteristic of her later novels, E.M.D. pricks the bubble of her expectations: cautioned by Lady Isabel ‘”never more than three dances”, Alex bore the warning carefully in mind, and was naïvely surprised that no occasion for making practical application of it should occur.’ Alex fails to attract.

Desperate not to disappoint her mother, Alex allows herself to become engaged to the good-looking, socially acceptable, self-obsessed Noël Cardew, and the only good thing to come out of it is a rare moment of warmth from her mother. Could the marriage have worked? Noël is a bore, who finds women shallow and deplores sentimentality, but he has a philanthropic vision for the estate that he will inherit, which he had hoped to share with her. But Alex needs more (Noël has a point when he describes her as ‘exacting’). She breaks off the engagement. In a rare moment of insight, she is conscious that this ‘sudden impulse’ is likely to have far-reaching and disastrous consequences. Quite far-reaching and how disastrous she does not realise. ‘Like all weak people, she had an irrational belief in sudden and improbable accessions of luck.’ Chance but not luck determines the rest of her life.

Noël, in all likelihood, will be fine. He will find a less exacting wife, who will be ready, eager even, to put up with his egotism, his coldness, his lack of interest in sex, for life as a married woman. Noël will not need to change or adapt. While Alex is warned that as a spinster she can look forward to a life of semi-penury, her good-looking, feckless brother, Archie, will have his debts paid by his rich sister-in-law and look forward to a successful career as a guardsman. It was a man’s world. Alex’s prospects were grim.

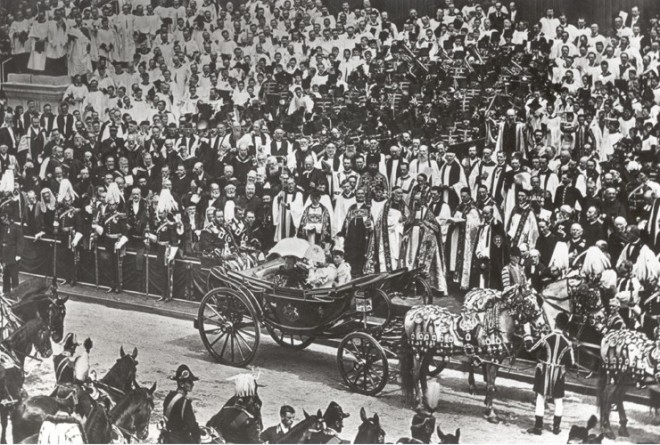

An unplanned visit to a Bayswater convent, a rest from the heat and exhaustion of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee parade, proves to be the defining moment. Alex has little real interest in religion. Her father is Catholic, but we do not see him at his devotions. Her mother knows ‘lots of people who go to Farm Street’ (still the most fashionable of London Catholic churches) and accepts church going ‘if it is at a reasonable hour’. But the Church is able to provide, for a while, what Alex so desperately needs: a refuge, where social skills are not a requisite, and which can accommodate misfits. The vexing question of marriage can be forgotten.

The regime is a harsh one, but, for some, like Alex, easier to adapt to than the unforgiving Victorian society of the 1890s. Most importantly of all, in the figure of Mother Gertrude, convent life offered the maternal love for which Alex remained so desperate. Or something like it. Alex mistakenly thinks that, in becoming a nun, she can revert to childhood and remain there. But Mother Gertrude moves on. Alex is not her child. In another impulsive move, she decides to leave the convent community, which, like everyone she has ever known, has disappointed her.

Alex was not in any useful sense grown-up when she entered the convent. For ten years she lived there in a state of arrested development. She is no more fit for the world outside than when she went in. Travel, money, the need to telegraph ahead to others, even the necessity for sandwiches for the train – all such practicalities are beyond her.

People are kind to her, as far as they are able, but she gives little in return, not even a polite interest in their lives. Delafield, who has not always had sympathy for her (anti) heroine acknowledges with pity ‘that terrible isolation of those who have definitely, and for long past, lost all self-confidence, and which can never be realised or penetrated by those outside.’ It is impossible not to be drawn into the last months of Alex’s dreadful downward spiral. I am not sure that pity is the word, more a sort of grim realisation, with her, that there is no other way, and a sad salute to her final moment of pride, ‘because she knew that for this once she was not going to fail’.

Questions

At times Alex seems to feel that she is destined to fail, to be a misfit, blaming fate, the Creator, the Devil,and most of all she herself. It never occurs to blame her parents, or the system. Is there a point at which you think she might have been able to change things for the better?

Many people have assumed that at the heart of Alex’s story is her sexuality, and that this was just one more issue swept under the Victorian carpet. Do you agree?

Nicola Beauman (cf. the Preface) calls this ‘a deeply feminist book’. Do you agree? Is it caught in its period, or can we see something of ourselves in the restricted lives of late Victorian women?