Slight and grey-haired, in a cool grey dress, relaxing in a shabby wicker chair under the lime trees, Mrs Fowler keeps a pile of books on a table beside her to ‘dip into’. A Persephone reader before her time (one can almost picture a few pale grey covers in the pile), she is immediately sympathetic as a character. Stout Mrs Willoughby wears rich dark silk, has heavy mahogany furniture and does not think much of novelists, ‘they were people who wasted their time writing novels so that other people might waste their time reading them’. She would not be on the Persephone Biannually mailing list. Two women in their late forties, both widows, young widows by today’s standards, each with five children of similar ages, they have nothing else in common apart from some shared grandchildren, to whom Mrs Willoughby, with no justification, lays the greater claim.

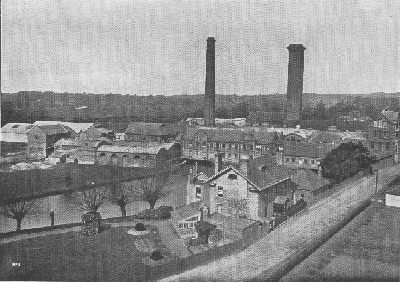

At first everything about the Fowler household seems as attractive as the Willoughby ménage is off-putting. The fading colours, the soft, slightly sagging furniture, the welcoming fire even in June, the books, the aged cook, all suggest the quiet, easy confidence of old, if much reduced, money. Langley Park is a house which has known better days, whose rural setting has been encroached on by new developments, but which still retains one good view, away from the town, where the Willoughbys live, at The Beeches, a house in which ‘nothing was allowed to grow shabby or faded as it was at Langley Place’. The Willoughby money is ‘new’, flowing from their ‘monstrous’ paper-mill which looms over Bellington. They don’t just live in Bellington, they are Bellington, pillars of Bellington society. Unsurprisingly Mrs Willoughby considers the Fowlers to be lacking in the solid civic virtues. ‘All they ever seemed to do for the community was to hold a fête in aid of the Conservative Party in their garden each summer, an occasion that was, in Mrs Willoughby’s opinion, more a display of their roses and sweet peas than of their public spirit.’

It is Mrs Fowler who describes the family as ‘a sort of roundabout’, characteristically accepting an inevitability in the way patterns repeat themselves from generation to generation. Juliet Aykroyd makes the point in her preface, that roundabouts exert centrifugal as well as cohesive force. Here we have two families, two roundabouts, each spinning around the still point of a powerful matriarch: the late Messrs Fowler and Willoughby have left little trace. Mrs Fowler relies on the natural centrifugal pull to keep her brood together, making no obvious effort, and ultimately with only limited success, while Mrs Willoughby gives the laws of physics a helping hand, using her own tight reins to maintain her hold on as many aspects of her children’s lives as she is able, a hold which, to her chagrin, will not prove strong enough to restrain her grown-up grandchildren.

It is hard to warm to Mrs W. She is not a kindly mother: ‘she either ignored you or turned on you the full and blasting force of her authority’, but her disciplinary approach was not unusual for its time. She shows some indulgence towards her sons, eventually, but too late, relaxing her grip on the younger, and showing a glimmering of psychological insight into the older: ‘she had few illusions about him, but she had found that if you persistently credited people with a quality they often ended by acquiring it’. To her daughters she gives no quarter; the submissive older ones buckle to her views on child rearing, furnishing, and fashion, while the youngest escapes only by a whisper a life as the family dogsbody. However, Mrs. W is not an unkind person. A host of poor relations form a regular part of the family circle, attending the regular Sunday suppers, which she prepares herself, and unostentatiously subsidizes from her own purse. She makes a conscientious effort to understand Mrs Fowler, but fails.

Mrs. Fowler’s Sunday teas are more relaxed affairs, but they are prepared and served by loyal staff, and the circle of deck chairs is a small one: friends are welcome to drop by, but there is no place for dull needy relations. As a mother she is uncritical and undemanding. When her favourite son, Peter, admits to an affair with his daughter’s nanny, she shows no disapproval, ‘only a depth of love and pity’ – the fact that nanny Rachel is a ‘lady’, while his wife, Belle, is an overdressed neurotic, with ‘a diseased appetite for flattery’, not unlike Lena in Saplings (Persephone Book No 16), may not be insignificant.

When her youngest daughter, Judy, returns home, pregnant, and alone having left her husband, she is welcoming and uninquisitive. Hers is a gentle but oddly passive style of mothering.

Having from the earliest days of her marriage decided to repress the more assertive side of her character, who she likes to call Millicent, in favour of the more submissive, easy-going Millie, she is uncontrolling to a fault. Aware from their childhood of the jealousy festering between her daughters Anice and Helen, she did nothing. She ‘dimly understood the dark and obscure forces that had made Matthew [her eldest son] hate Peter’ but stood back. Towards Helen she is astonishingly cruel: when she notices her unhappiness (Helen rightly suspects her Willoughby husband of being unfaithful) she is surprised at the pain it causes her, noting that ‘it would have amused Millicent’! What a good thing Millie, and not Millicent, did the mothering. At least the neglect was benign. But it was neglect – from their earliest days taking them on picnics, she ‘would sit on the log, reading, completely forgetful of them’. She is right to experience a ‘feeling of inadequacy with all her children’. But she is imaginatively helpful to her grandchildren, and to Mrs Willoughby’s.

Richmal Crompton is not judgemental. It is clear that both women have their strengths and weaknesses, that benign neglect, though more beguiling, can be as damaging as iron control, that intuition can be as valuable to understanding as conscientious effort but that both are important, and that, in the end, children are as much a product of nature as of nurture.

The Tea Room by Mabel Layng @ The Hepworth, Wakefield

One should not forget that both these women have suffered the loss of their husbands and the challenge of bringing up large families alone during turbulent years. Matthew Fowler’s youthful (he was only 20 at the time of his father’s death) escape to Kenya must have been at least in part an escape from unwelcome responsibilities; Helen’s bossiness may be the result of a perceived need for someone to fill the gap. The reaction of the two youngest girls, only ten when their fathers died, is delayed but predictable. Judy’s unsuitable attraction to her godfather and the relationships that she and Cynthia have with the odious and vain, middle-aged novelist, Arnold Palmer, clearly suggest in both the need for a father figure. Later Judy finds solace for the loss of her brother, and the loss of her own childhood, by returning home to recreate, relive those years with her new baby.

Richmal Crompton observes but does not probe deeply into the impact of childhood bereavement. Child psychology was in its infancy: astonishingly Peter’s daughter, Gillian, is told only as a teenager that the man she thinks of as her father is in fact her uncle, and even more astonishingly receives the information with total equanimity. But she does write brilliantly about children, and for all that the subject matter of Family Roundabout is essentially serious, a rich vein of humour runs through it. The poor relations are almost Dickensian and the spirit of Crompton’s own William lives in Tim, whose reluctant appearance in white silk at his uncle Max’s wedding is memorable.

Written in 1948 and looking back to the period between the wars, Family Roundabout is noticeably silent about the war that has passed, and which the menfolk appear, remarkably to have survived. The coming of the next war is barely alluded to. Mrs Fowler can’t bear the possibility and is reassured by an article in a spiritualist magazine affirming that there will be no war, while equally typically, Mrs Willoughby dismisses the very idea because Hitler is nothing but a ‘common little upstart’. But we can picture them in a few years time: Mrs Fowler will surely be a member, if not the most competent, of the Bellington sewing party, while Mrs Willoughby organises the billeting of evacuees. Crompton has created two very real characters.

Family Roundabout is a subtle novel. Problems of marriage and parenting and growing up and being a woman in a man’s world that form the focus of so many Persephone books are treated wisely but lightly. It would be far from true to say that everyone lives happily ever after, but most accommodate themselves to their life, not perhaps the one they dreamt of, but one which will do, and whatever the drawbacks, has its compensations.

quotes … do share your favourites

‘It isn’t that she can’t fight, it’s that she can’t be bothered to. And the Willoughbys amuse her. She likes to see them in action. She’d put a few spokes in their wheel just for the fun of the thing, but not enough.’

‘Mrs Fowler and Mrs Willoughby were talking together in the middle of the lawn, but they suggested a couple of generals conducting a parley during an armed truce rather than heads of a united family.’

‘She had this feeling of uncertainty and inadequacy with all her children. She shrank from bringing pressure to bear on them in any way or obtruding on their privacy, and so, she suspected she often failed them. They wanted help and advice, and she had none to give … Her thoughts went t Mrs Willoughby. She can always give people advice. I’d be better if I had more of her in me. A little smile twitched her lips. And perhaps she’d be better if she had more of me in her …’

‘you can be a slave to freedom, you know darling, as to anything else.’

If you have enjoyed this book, you might also enjoy:

Someone at a Distance by Dorothy Whipple (Persephone Book No.3)

Saplings by Noel Streatfield (Persephone Book No.16)

They Knew Mr Knight by Dorothy Whipple (Persephone Book No 19)

The New House by Lettice Cooper (Persephone Book No. 47)

What other bloggers have said about this book:

The character I absolutely loved: Mrs Fowler. Such a gentle soul but with a fire that she has kept tamed over the course of her married life. … She is the grandmotherly figure you want to run to when something is wrong.

The character who I loathed: Belle. One could maybe choose Helen or Mrs. Willoughby for this distinction, but they are both pussycats compared to the atrociously petty, self-centered Belle. God I hated her. A bit of an archetype, she is the one you would hiss at when she came on screen if this book were a film. (I wish.) myporchblog

All the adults have issues stemming from their childhoods, affecting their parenting, and it made me wonder if adding a couple who had sufficiently dealt with their issues and who were, on the whole, good parents though not infallible would have made a difference to the novel. On second thought, though, I don’t think it would because even children raised in good homes make poor choices later in life. After all, it’s part of being human to fail sometimes. Furthermore, probably nobody sufficiently deals with their issues enough so that they don’t affect any children they may have. aliterarywayfarer

And Crompton has a wonderful ability to portray characters of great depth and breadth. They each have very unique characteristics, personalities and voices, so even though the cast of characters was long, I never felt confused by them all. There’s a subtle humor to the story as well. It’s not necessarily laugh out loud funny, but Crompton didn’t seem to take her characters too overly serious either. She reminded me just a tiny bit of Barbara Pym. danitorrestypepad