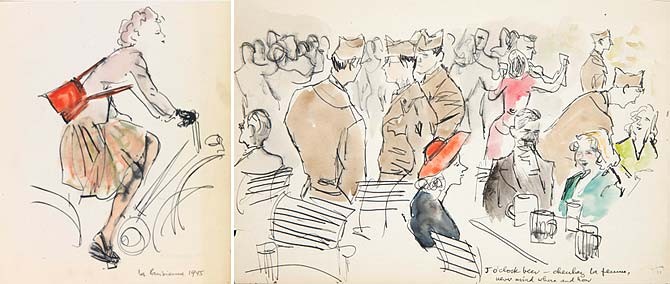

In 1937, ten years before she wrote Little Boy Lost, Marghanita Laski was married in Paris to John Howard, a publisher and author of a number of books on French history and politics. They lived in France for a year and returned many times after the war – for holidays which, according to her daughter, often included visits to orphanages. Her detailed descriptions in Little Boy Lost – the bombed factory, the makeshift bridge, the shattered rusting locomotives, Paris without taxis or buses – are informed by her personal experience of the physical and moral impact of the war and the Occupation on a country she loved.

She gives her hero (and yes, I do think he is a hero, if not a very likeable one) her own fascination with France, its literature and its people – not all of its people, but certainly the intelligentsia. Hilary Wainwright is a soldier, desk bound as a result of a wound, and surely by temperament and aptitude (his sister refers somewhat disparagingly to his ‘hush-hush’ work), a poet and a critic, able to quote sixteenth-century French verse, as well as Coventry Patmore, sought after as a contributor to literary journals on both sides of the Channel.

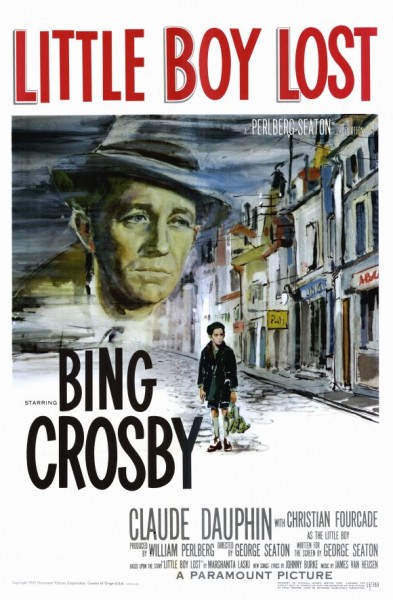

Laski was one of a small number of women on the much respected television programme The Brain’s Trust. Like Hilary she would not have been ashamed to admit that it was among intellectuals that she felt at home. No wonder she hated the 1953 film of Little Boy Lost. Bill (Hilary being presumably insufficiently masculine a name) Wainwright, is an American airman, a journalist, played by Bing Crosby – there are songs.

The attraction of Little Boy Lost for a screenwriter is obvious: post-war Paris plus the undeniably exciting and moving story of widower’s search for a lost child. Laski paints the background perfectly, from the grey-shattered houses to the beige distempered walls, topped with a mock Egyptian stencil. The tentative steps towards a relationship that is unfamiliar to both man and boy are perfectly described. She draws us into Hilary’s dreams of a future with Jean, a future in which there would be trips to the circus and Madame Tussauds and the pantomime, where he could be both father and child, where the confident five year old Hilary in neat grey shorts and tidy socks and the skinny little waif in a black overall could start again. We long for his present to Jean, some tiny red gloves, to be the first of many. And the moment when he decides to follow a sexy black marketeer to Paris, accepting that he has seen Jean for the last time, is both heart-breaking and enraging. Can he not commit after all? Must little Jean, who stands for all the lost children of Europe, remain in the orphanage, with his single, broken, toy and his one book, under the not uncaring, but unsentimental eye of the Mother Superior?

It is a brilliant story, unputdownable. And it is a complex novel, tightly written, with occasional flashes of irony, which asks challenging questions, about human behaviour in war, and in peace, about love and morality, and most importantly about action and inaction and our responsibility for our choices. We are not asked to side with any one of the three main characters, Hilary, Pierre and the Mother Superior, all of whom speak at times with the author’s voice. There is not always a right or a wrong choice but there are always consequences.

Laski and her husband, the Francophiles, would surely have been familiar with the early works of Sartre and Camus, and there are certainly elements of the existentialist anti-hero in Hilary Wainwright. We first meet him as ‘the outsider’ at his family’s Christmas, coldly observing both the celebrations and his own reactions, a man who, starved of maternal love, and robbed by the Gestapo of his wife and son, has elected to live in a kind of emotional limbo. His war career, by his own admission, has been a ‘stay-at-home’ one. He has chosen inaction, relying ‘on a drug of remembered happiness’, preferring to be left alone, ‘so that I can’t be hurt again.’ When the Frenchman,Pierre, arrives on Christmas Day to tell him that his son is lost, but might just be traced, he cannot admit his ‘deep unwillingness’ to search for the boy, but avoids it for as long as is able, lying about the possibility of getting leave, and denying the existence of, potentially helpful, photographs of himself as a child. Later he writes to the Mother Superior, in charge of the orphanage where the boy is being cared for, telling her that he has been called away on business and must delay his decision on the child. ‘Once she has read this letter, I can never come back, but I can still pretend not to know this … I will not let myself believe that I am lying.’ Two examples of ‘Sartrian’ ‘bad faith’.

Hilary writes an article on the surrealist poet Max Jacob. Jewish by birth, Jacob was arrested in February 1944 and died in the internment camp at Drancy while awaiting deportation; yet in the novel there is almost no mention of the fate of French Jews.

By contrast, Pierre is a man of action and honest with himself. He has been with the Free French in Algeria, and worked ‘underground’. In 1945 he is prepared to throw in his lot with de Gaulle, in spite of reservations. He, like Hilary, has lost the woman he loved, but while Hilary has turned his face to the past, Pierre looks to the future. Fearing that it would compromise their Resistance group, he had disagreed with his fiancée about taking in Hilary’s child to save him from the Germans: Jeanne’s view, which Laski offers as it were for discussion, was that ‘we should each do good where it is near to us, where we can see the end of it, and then we know that something positive has been done.’ Later, after Jeanne’s death, Pierre looks for the child, as a kind of expiation for his failure to support her, and because that was what she believed in.

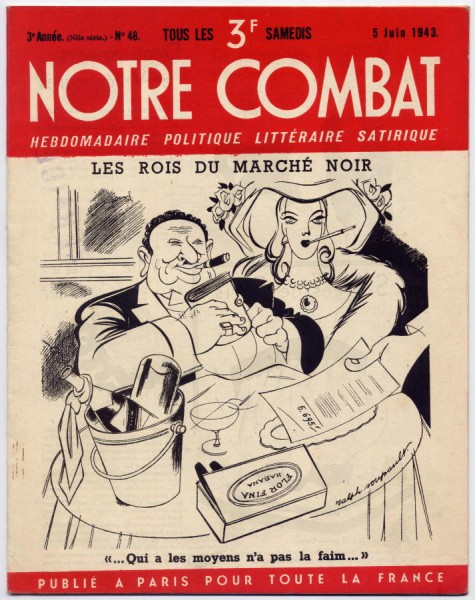

Pierre is able to move on. Principles are good, but should not be carved in stone. By contrast, there is something stifling about Hilary’s moral rigidity. When, somewhat piously, he asks Pierre after the war, ‘Don’t you wonder with every stranger you meet, what he did under the Occupation?’, he finds that his friend has put it all firmly behind him. ‘I’m tired with “collaborator” as a term of abuse; we each did under the Germans what we were capable of doing; what that was, was settled long before they arrived.’ Pierre is a wise man: Hilary despises his lack of intellect, but Hilary is an intellectual snob. Pierre is also a good man, who knows that total honesty towards others may not always be the best policy but, unlike Hilary, is honest to himself: knowing that there are two other boys either of whom might be Hilary’s son, he chooses for honourable reasons to remain silent.

The Mother Superior, too, is a good woman, and like Pierre she a perceptive pragmatist. Hilary is shocked by her frank acceptance that charity must be weighed in the balance, blind to the fact that he weighs everything but with a different set of scales. Food is short, money is short, and she would like Hilary to take Jean, for the good of the orphanage, but also for the good of the child, in whom she has recognised something special, and for the good of his ‘father’, in whom she has recognised a damaged and needy soul. Hilary, like many damaged people, is at the same time self-centred and lacking in self-awareness: he barely understands what she is saying.

The nun has little time, either literally or metaphorically, for Hilary’s ingenuous (intellectuals are not always intelligent) concern for such niceties as protecting the healthy children from the tubercular, but she recognises that he is in need of comfort, another lost boy, who needs to be loved, and to love. In a rare moment of insight Hilary himself recognises that he is jealous of his dead wife’s feeling for John/Jean. ‘Did I give? Was I ever capable of giving?’ Laski engages our sympathy for her flawed hero, but does not let us forget the flaws, avoiding all risk of sentimentality in the final pages by revealing a coarse sexuality.

The Second World War left 13 million European children without one or both of their parents. In 1948, a year before the publication of Little Boy Lost, 20 000 were still waiting to see if any relations could be traced. In France in 1945 there were estimated to be 350,000 orphans. The task of reuniting them with one or other parent had only just begun and for many would never end.