If there is a lesson to be learnt from Minnie’s Room: The Peacetime Stories of Mollie Panter-Downes, it is that peacetime can be harder than wartime. In her Wartime Stories Mollie Panter-Downes, with her delicate brushstrokes, and (mostly) with sympathy, painted people at their best and at their worst – the old cliché is only partly true. Faced with unwelcome guests, shortages, unfamiliar domestic chores, or quite simply change, her characters reacted with courage, impatience, irritation, anger, often with excitement. Uncertainty about the outcome of the war, or its likely duration lent an edge to their response. Would the ‘friends’, the relations and the evacuees be staying for months or years? How long before cook, housemaid or gardener returned? When would it be possible to move back into the old home? After the war: that phrase, which must at times have seemed fairly elastic, at least held the promise of an end to things as they were. For some not so much a promise as a threat: the companionship, and the sense of purpose, the feeling that ‘we are all in this together’, the excitement, could not last.

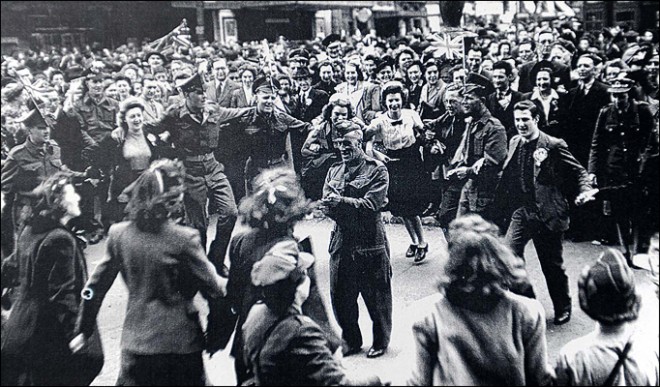

That ‘after the war’ might not be same as ‘before the war’ was a concept that not everyone recognised or welcomed. The problem with peacetime, is that there is no ‘after’, no ‘when this is over’, no ‘when things get back to normal’. The tightened belt, the crowded home, the absence of domestic staff could no longer be thought of as mere temporary unpleasantnesses to be borne with a stiff upper lip. This was the new normal. The end of the war brought with it a new social order, in which there would be new winners, and new losers, casualties of peace, not fatally injured, just ‘walking wounded’.

The first stories of Minnie’s Room, written in 1946 and 1947, can be read as a sort of coda to Good Evening Mrs Craven. Hostilities have ended, but these characters are facing a new struggle, to which they are barely equal, quite literally so in some cases, Mollie Panter-Downes suggests. ‘Since the war, the Sotherns had visibly shrunk’, apart, that is, from Mrs Sothern, who had developed heart trouble and was an invalid. Their Bayswater house, pleasantly large when filled with staff, with no-one to do for them, becomes worryingly big; the well stuffed furniture and the plush curtains once so comfortable, seem to be smothering them. Meanwhile in Westminster, the Stanburys are threatened by the monster of Things, a dragon out to devour them and their kind, ‘to devour their modest, honourable incomes.’ And, in a seaside nursing home, the Dodds must decide what to do with their frail elderly mother, who, before the war, would have expected, and been expected, to live out her declining years in the capacious family house.

All are forced to find solutions to problems, which for people of their class, had there been no war, would never have arisen. A room is found for old Mrs Dodd (one can only hope that there might be a corner somewhere for Nannie, who has cared for her so devotedly and with so little thanks). The Stanburys flee, more unhappily than either of them imagined, to South Africa, dragging behind them the Surtees first editions, the polo cups, the rugs, and ‘bit of his mother’s things from the old home in Somerset’, cumbersome and pointless relics of the past. The Sotherns stay put, with only their unmarried daughter to care for them – she ‘did everything’, ‘everything’, as her mother tells it, ‘she changed the library books, stood in the queues, and exercised the cairn terrier in Kensington Gardens’.

Poor Norah, her dancing days are over, and unlike her bachelor brother Maurice, who is able with no difficulty, or guilt, to move in with a friend, she is tied to her anxious, ageing parents, who must manage without their long-serving, and underappreciated, cook Minnie. No wonder Norah envies Minnie’s freedom, and her little room at the top of a gaunt house, south of the river. The Sothern’s cook is one of the winners: free at last from domestic service. Things won’t be easy for her, but, like Mrs Dodd’s unmarried daughter, Cynthia, Minnie will have a room of her own, and a life of her own. To be a spinster after the war carried with it none of the shame of earlier years; there were jobs and there were ‘bedsitters’, and women had grown accustomed to meals on trays.

War had taught them strength and, while many women, more or less happily, relaxed back into pre war habits of obedience to husbands or parents, or simply convention, others had seen another way. Three stories deal with what are considered, either by family or friends as ‘unsuitable’ marriages, unsuitable in different ways, but in each case defying already crumbling class barriers, the same crumbling of barriers that had allowed Minnie to escape, and left the Stanburys unprotected against their fears. In a world in which for a woman to remain unmarried is not the unmitigated disaster it once was, why not marry for love? Take the risk. Forget about the parents’ expectations.

Horace Lessing had been confident that ‘it would not be long before [his daughter] was married to one of the nice youngsters who ran her around to parties and tennis. It had not occurred to him to look for his future son-in-law in a ditch, which was where he remembered last seeing George Tupper.’ How brilliantly Mollie catches Horace’s voice, and in so few lines tells the reader everything about Rosalie’s Home Counties life – one can see her stiffly-boned, full-skirted party dresses and her bouncy tennis frock, even the faintly battered sports cars of her ‘suitable’ escorts. But when, having defied both sets of parents, Rosalie and George marry, what Horace feels is not anger, but envy, the same sort of envy that Norah Sothern felt for Minnie, the ‘ugly little Londoner’.

Most of the stories in this small, but perfectly chosen selection, describe episodes in the lives of adults, often families, invariably moderately, though never catastrophically, dysfunctional, in which children and parents are all grown-up. Only two focus on young children and they are quite outstanding. ‘What Are the Wild Waves Saying?’ and ‘Intimations of Mortality’, both date from 1952, and both are written in the first person, a woman looking back at an event, hardly even an event, a moment in her childhood. What is truly remarkable is that nothing happens, and yet nothing will ever be the same again. They are classics of the genre. In the first a fourteen-year-old girl on a seaside holiday with her cousins learns a profound lesson about love, which blows away all her teenage romantic fantasies, ‘Mackerel Bay had slipped into my hand a cold, faintly pink shell, which would sing against my ear a song without words and, I guessed, without end’. In the second a seven-year-old, on a brief, unscheduled outing with her nanny meets deprivation and adult grief for the first time. and realises dimly, but forever, the meaning of unconditional love. Mollie captures so accurately the emotional maelstrom in the little girl who lacks the vocabulary for the situation, ‘my overcharged heart had decided to seek relief and call attention to its own woe … I began to behave badly, because I so longed to show her that I loved her’. Almost all the stories in the collection deal with loss in one form another, loss of status, loss of property, of confidence, of youth. What is lost in these two is innocence, but innocence is replaced by understanding. Loss need not be bad.

A strain of melancholy runs through Minnie’s Room, but it is invariably lightened by Mollie’s wry humour, her piercing eye and her ear for dialogue, and, most importantly, by her own optimism: the future may be uncertain but for those who have the courage and the vision it is there for the seizing.

Quotes … do share your favourites:

‘Vestiges of everyone’s interrupted everyday business seemed to have trailed into the room with them. Grasping handbags or gloves, they sat forward on their chairs like strangers brought together in a railway waiting room by some accident on the line.’ (‘Beside the Still Waters’)

‘Cecily sometimes noticed Mr Kent gazing at her father-in-law with romantic respect, as though he detected on the old man’s food-spotted waistcoat a plaque that said, “In this building, now ruined, Edward Monroe Darlington lived for many years”.’ (‘The Old People’)

‘He was badly dressed, and I noticed that this seemed to have provoked a joyful answering trill, so to speak, of dowdiness from Betty, who wore, for the first time since I had known her, a really unbecoming dress.’ (‘The Willoughbys’)

If you have enjoyed this book, you might also enjoy:

Good Evening, Mrs Craven: The Wartime Stories of Mollie Panter-Downes (Persephone Book No.8)

Tell It to a Stranger by Elizabeth Berridge (Persephone Book No 15)

A Woman Novelist and Other Stories by Diana Gardner (Persephone Book No 64)

The Persephone Book of Short Stories