‘Catherine had always supposed that a family was a united whole from the beginning. Life wasn’t as easy as that.’ Hostages to Fortune opens with the birth of Catherine’s first child. The birth of a first child to Catherine and William, how fortuitous that this should be the Forum book for this month.

But this is 1915. William, Catherine’s husband, a doctor, is at the Front and she is alone when she experiences that first astonishing realisation, surely familiar to every new mother, ‘That’s not a baby, it’s a person’. She cannot share it with William , who celebrates the arrival of his daughter according to convention by offering his friends a dinner of Langouste Américaine.

They are no closer when he returns from France. She ‘felt that the War had given her back quite a different person from the one she had married’, while ‘William’, writes Elizabeth (it is a feature of Persephone authors that sometimes one finds oneself thinking of them by their first name, not always but often, and Elizabeth Cambridge is one of these), was disappointed’. His wife, the bride he had come back for, looks shabby: baby Audrey has taken Catherine from him. He responds by taking Catherine back for himself. Catherine must hand her tiny daughter over to Nanny. From the beginning this little family is far from united.

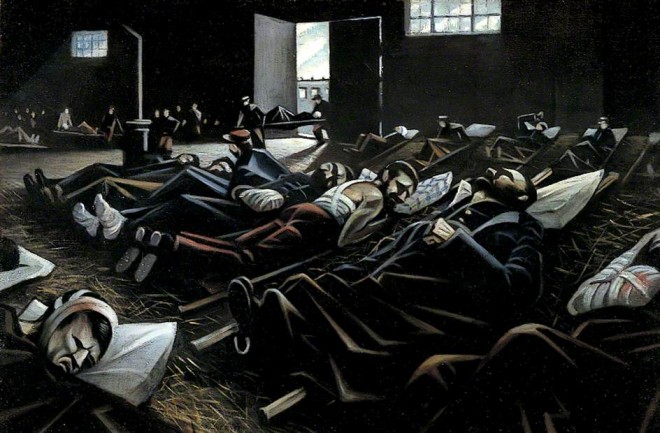

‘La Patrie’ by Christopher Nevinson. 1916. Birmingham Museums Trust

Three years of gangrene, mud and marauding aeroplanes, when planning a road provided a welcome measure of sanity, and order, have left William with an uncomfortable need to control house, garden, children, Catherine’s wardrobe if he could. She like other women of her generation is tired, daunted by an overlarge house, ‘the exact opposite of the house of her dreams’, lacking the staff for which it had been built: Quentin Bell in his life of Virginia Woolf urges us to remember all the labour saving devices we take for granted before we scoff at our forbears for their dependence on servants. And Elizabeth does not overlook the dire conditions from which Catherine’s loyal maid of all work, Irene, springs, nor the bleak future facing her family.

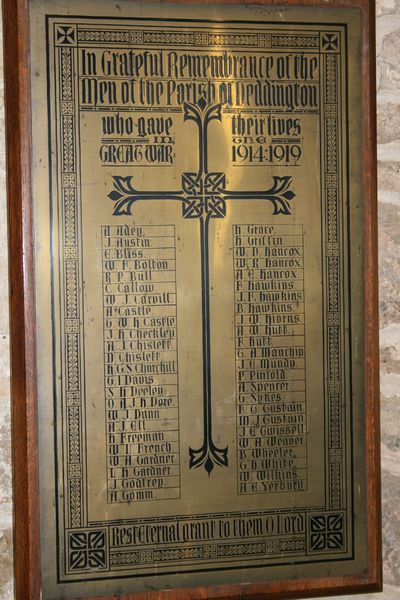

The war, which ‘absorbed her generation like a sponge’, has left those who remain not ‘ripened’ but ‘scorched’. Husbands, sons, lovers, friends have been lost and dreams turned to dust. Catherine’s determination not to ‘hand that pain and weariness on to her children’ cannot keep the shadow of the War from casting a pall over their early years, a time of shortages, and inflation, change, and regret for lost opportunities. It is a weariness that will not leave them: in the early 1930s her friends, robust women like her, complain, ‘We started doing too much in the War, we found we could do it and we went on doing it. Now the bill is coming in.’ And, of course, what they don’t know and what Elizabeth didn’t know, was that a new challenge was already looming, one that would threaten and maybe take the lives of the very children to whom they had devoted so much energy. Hostages to Fortune was reviewed in The Times Literary Supplement on 23rd June 1933. Hitler had been Chancellor of Germany for six months.

Curiously, the reviewer described Hostages to Fortune as ‘a very happy novel’. Extraordinary – but perhaps no more so than The Times obituarist in 1947 who summarised it as ‘a finely observed interpretation of the life of a country doctor’! Surely if Hostages to Fortune has a message it is that contentment is achieved only when happiness has been recognised as the chimera it is. It is not reached by striving for it, any more than the perfect child is produced by consulting manuals, or feeding them on raw vegetables. Hilary’s mother, Catherine’s practical friend, is more use to her than Robin’s: ‘that’s life’, says the first, ‘or if it isn’t life it’s all that you or I are going to get my dear’, while the second seeks the key to perfect parenting in Freud and Froebel, Coué and carrots.

‘Hilary’s mother’, ‘Robin’s mother’: that is how we know them. Is it any surprise when Catherine says of herself, ‘she was Adam’s, she was Audrey’s, she was William’s’, and, when Jane, her sister’s unsatisfactory daughter, (only unsatisfactory because she did not follow the narrow, home bound path her mother had selfishly planned for her) argues for ‘a life of one’s own’, the concept makes little sense to Catherine, whose own dream of being a writer has been put away with her novel at the back of a drawer. Life for women, married or single was hard and the prospects for daughters, as Catherine is all too well aware limited. Men in the thirties were not having an easy time either, and William too is exhausted. A country doctor serving twenty-seven villages, making up his own medicines and constantly worried by debts, there are times when he hates his work.

But while neither is ‘very happy’, they are not unhappy. She is reconciled eventually to country life, adapting to the rigid village hierarchy. They find great happiness in small things, he in a row of fruit trees planted, and growing well, she in a house smelling of flowers and beeswax, in feeding a baby, in lying in warm grass listening to the bees. There is a sort of peace in quiet evenings together: ‘When they were not speaking they could think kindly of each other, glad to be together, much as two horses will stand together out of harness under a tree’ and joy in looking at her children, when she does not feel ‘obliged to interfere or correct them’. Time and again I wanted to say, ‘yes, Elizabeth, that’s exactly how it is, still’.

As a new mother Catherine recognised that Audrey was a little person, ‘all there … as a piece of fine material is packed in a small box’.

It is a shock to find herself not always liking the person: Audrey is bossy and knowing, while her brother Adam is sweet and sensitive but not as clever as she would like, and the youngest, Bill, too masculine and aggressive. But Catherine is more accepting than William, who firmly believes that children of his own flesh and blood should have like natures, while she sees them as ‘acts of an incalculable God, created in the likeness of relations she had far rather they didn’t resemble.’ Elizabeth’s wry humour makes Catherine even more sympathetic. Worried that they have too few friends nearby, she finds her children getting ‘very cornery’ . What a perfect description; we know exactly what she means, just as we can feel and share her pleasure in ‘the slippered ease in being simply three women together’, and picture her clothes, that William hates for their ‘draggled, worried look’. I love the fact that my spellcheck is thrown into confusion by so many of her words.

Parenting is hard, Catherine is not the perfect mother, nor William the perfect father. Marriage is hard, and, against all expectations, being parents together doesn’t make marriage easier. Catherine senses rightly that William loves her for all the reasons for which she doesn’t want to be loved. She sees the two of them as starting ‘at opposite sides of a dense dark jungle’, and Elizabeth does not gloss over the black periods, times when ‘the sourness, the disillusionment, the mutual disappointment were poison to both of them’. In what the younger generation might disparage as a rather old-fashioned way they hold on, until ‘somehow a real friendship, a real need for each other’ has grown up behind their differences and disappointments. Their contentment has been hard won, but finally William is able love her for the person she is: ‘… she was a trier. Valiantly, in blind ignorance and recurring dismay, she had kept his house and brought up his children. Even if her efforts weren’t always successful, it was for them that he loved her.’

The title reminds us of Bacon’s epigram, but the novel challenges it; far from being ‘impediments to great enterprises’, their children and their marriage have proven to be the great enterprises. Is it a happy ending? I don’t know. I closed the book with tears in my eyes.