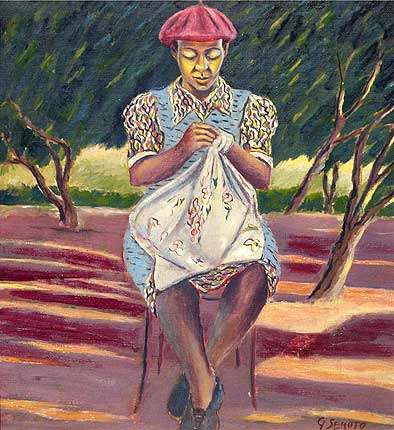

Ten men stood in the dock with Nelson Mandela in October 1963. Four of them were white: Hilda Bernstein’s husband, Rusty, an architect, Denis Goldberg, an engineer, and two lawyers, Bob Hepple and James Kantor. Harold Wolpe, also a lawyer and Arthur Goldreich, a noted painter and owner of Liliesleaf Farm in Rivonia, the ANC meeting place at which the men (apart from Mandela himself who was in prison, serving a five year sentence for treason) were arrested, had managed to escape from Pretoria Jail by bribing a guard. A team of five white lawyers defended all of the accused. Hilda Bernstein and Goldberg’s mother Annie travelled every day from Johannesburg to Pretoria to attend the seven-month-long trial.

Mandela – a Long Walk to Freedom, whose London première coincided with the announcement of Mandela’s death, pretty much ignores the part played in the struggle against apartheid by a few brave white men and women, many of them Jewish. Rightly the makers of the film focused on the appalling treatment of Mandela and his fellow Africans, on the iniquity of the justice system, on the length of their sentences, on the brutality of the prison regime on Robben Island. Denis Goldberg too was sentenced to life imprisonment. He served his twenty-two year sentence in Pretoria Central Prison where conditions were a little less harsh: apartheid ruled in prisons, as it did everywhere else – Hilda Bernstein tells us that even the Black Maria taking the men to and from the Palace of Justice has a separate ‘white’ compartment.

Goldberg is still alive and was one of the last friends to visit Mandela before he died, invited by his wife Graca to ‘stimulate his mind’. Surely he deserved a mention. Bob Fischer, the lead lawyer, and the only one shown in the film, was punished for his role in the trial, arrested shortly after it ended and charged with ‘furthering communism’ and ‘conspiracy to commit sabotage’. He received a life sentence, of which he served eleven years, dying two weeks after his release. In his autobiography Mandela himself gratefully acknowledges the friendship and the help that he received throughout his life from a large number of white South Africans. But white heroes aren’t box-office, not in 2013.

The World that was Ours paints a wider picture, covering the cruel history of white rule in South Africa, the deliberate destruction of black communities, the violent response to peaceful protests. It gives a clear account of the slow rise of the ANC (I didn’t know that it was founded in 1912), of the gradual and inexorable worsening of living and working conditions for the African majority, of the increasingly cruel retribution reserved for those of any colour who dared to step out of line politically, and it describes a country of lush beauty, and fruitfulness, and ease for those lucky enough to be able to enjoy it – she paints her own garden in loving detail. The difficulties faced by the small minority of anti-apartheid ‘Europeans’, were minor, of a different order to those of non-whites, and avoidable – they could have conformed, or left. To stay and to carry on the fight required a particular courage. Denis Goldberg summed it up, ‘Being black and involved (in the struggle) meant you had the support of many people and it meant you got to be part of a community. Being white and involved meant being isolated.’ It is this that Hilda Bernstein describes so vividly, so movingly, and with such modesty.

Isolation came in many forms. The Communist Party, still a legal organisation when they joined in the early 1940s, had no colour bar. ‘We were accepted by Africans,’ she writes, ‘because we were communists, and we became part of the movement for national liberation’. But the result of that commitment was to set them apart from ordinary white society. When the Suppression of Communism Act was passed in 1950, cold disapproval turned to official persecution: raids and arrests, trials, surveillance, restraints and government bans. By 1960 raids had become almost routine: hundreds of books, newspapers, pamphlets and letters were regularly removed from their house by the boxful. A permanent watch was placed on the home that for years had been open for friends to gather, to talk, or swim, pick fruit in the garden or borrow books. Thenceforth the doors were closed and locked. ‘They’ had imposed silence and loneliness on a house that had ‘murmured with people and sound’.

Banning laws originally applied in 1950 to undesirable organisations and their members, were being tightened (they remained in use until 1990) so that by 1962, nothing written or spoken by any banned person could be published or reproduced in South Africa. Large gatherings had always attracted suspicion.

A new act altered the definition of a gathering, ‘making it virtually impossible for a banned person to go to a cinema or have a cup of tea with a friend.’ A bridge party or a game of tennis might be illegal. When Bob Fischer’s wife, Molly, died, friends had to get permission to attend her funeral, a ‘gathering’ by definition, and Hilda was unable to deliver her tribute. Her words were spoken, anonymously, by one of the Rivonia lawyers – I defy anyone to read this passage with dry eyes. In 1964, after the trial, seeing off a friend at the airport, Hilda sits at a separate table: both women are banned and forbidden to communicate. They must say their hurried goodbyes in the ladies’ toilets, out of sight of the Security man. The friend was Ruth First, the wife of Joe Slovo. Fourteen years later she was killed by a letter bomb in Mozambique, on the orders of the South African Police.

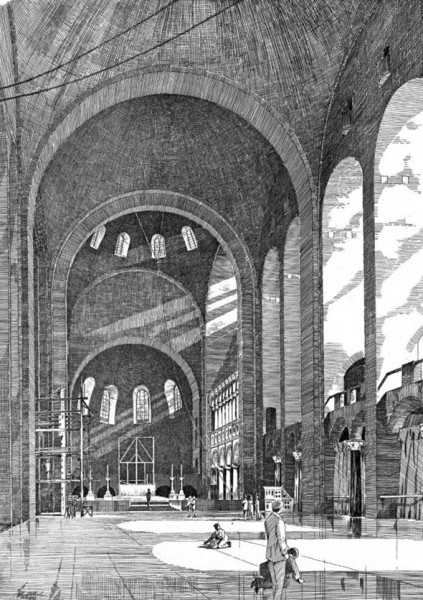

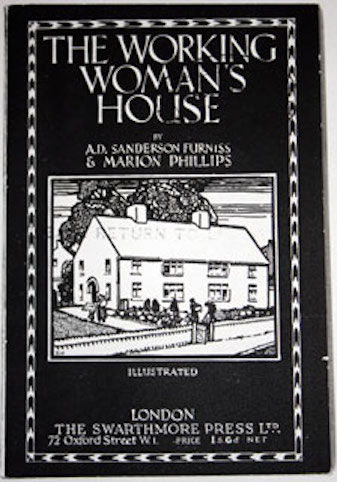

Banning laws and the terms of house arrest, to which Rusty was subject, made working life next to impossible. While Hilda was forbidden from publishing articles even in Amateur Photographer, Rusty had been forced to leave his architectural practice and work at home: builders and engineers could not come to the house and site visits had to be fitted around compulsory daily visits to the police. When their grown-up daughter, Toni, invites friends to the house – and she makes a point of doing so, regularly informing journalists about their visits – he must eat in a separate room. But with a wife and four children, still swimming and shouting and playing jazz records, Rusty’s home life, diminished as it is, seems almost normal compared to those under complete house arrest; Hilda describes them as ‘prisoners forced to provide their own food and lodgings’. Deprived of work and communication, these people were subjected to ‘a punishment worse than ordinary imprisonment, one potentially destructive to the individual.’ Isolation was a powerful tool in the régime’s armoury: it could break a man.

In 1963 the police were handed a new weapon: the ninety-day order under which anyone could be arrested (and repeatedly arrested) without charge or warrant and held incommunicado for ninety days, long periods in solitary confinement, without books or paper or visits. These were the conditions under which the Rivonia accused were held for four months while they were awaiting trial. Hilda had experienced imprisonment, arrested with Rusty and jailed for three months after the Sharpeville shootings -‘Not a hardship for me’, she writes with characteristic stalwartness, but hard on the children. Her job now would be to persuade lawyers to take on the case. Meanwhile she fought to be allowed to visit her husband, each visit requiring a fresh battle with the head of the Rand Security Branch, a lone woman against an unyielding system.

Rephrasing W.H. Auden, Hilda writes that suffering ‘takes place while I shop and look after my family.’ Throughout the pre-trial period, and for the long months of the trial, she, like most of the other women (some had made the equally hard choice of leaving the country with their children) carried on her daily lives as best she could, caring for her family, making the ordinary everyday decisions, like any mother on her own, except that she kept a packed bag beside the bed in case of a night-time police raid, and travelled day after day to observe a travesty of justice taking its course. We know the outcome, but the drama and the daily anguish draw us in, so that we are living it with her.

When, at the end of the trial, Rusty is discharged and immediately re-arrested on new charges, the Bernsteins decide, after thirty years of fighting apartheid from inside South Africa, that it is time to leave. Hilda looks down on their house and acknowledges that: ‘No one can live indefinitely on the edge of disaster. Our ability to survive all these years of abnormality had been due precisely to bring an everyday normality into our lives.’ Having returned from her temporary hiding place to take her youngest son to his new school, almost her last task is to put the washing in the machine, as if bequeathing normality to her family, before setting out on a hair-raising journey which would eventually take them to London.

The Bernsteins’ tortuous escape, by car, cart and truck, and on foot, via Bechuanaland (now Botswana) and Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia) would rely on the help of countless others, some friends, many strangers, some of whose names they never knew. In the weeks before they left Johannesburg Hilda had been hidden by a friend’s neighbour. While in prison Rusty and his fellow detainees had been able to count on their wives and friends; many of the Africans, held in far worse conditions, had no-one to bring food or clean clothes. Hilda describes the tireless efforts of a poor Indian woman collecting food, and cooking and delivering meals to men she had never met. This is the kindness of strangers and Hilda proves convincingly in The World that was Ours that for all its brutal efforts to keep friends, and families apart and isolated, the régime was powerless against that.