It’s VE day, and somewhere in the Home Counties, while the rest of the village is celebrating, two women make up their camp beds for the last times at the Red Cross Post: ‘… with those Germans you can never be quite sure. It would be just like them to have a last raid, just for spite, knowing we was thinking it was all over and done wit,’, says one. ‘Yes, it would be funny if the only casualties we had in Priory Dean were on the very night war ended,’ replies the other. The ‘we was’ of the first is sufficient to define her class, confirming what we might have suspected from the way in which the two women wear their wartime scarves, Mrs Wilson in a turban (working class) and Mrs Trevor knotted under her the chin (upper/middle class). The war has disguised the differences, both in their navy serge trousers and tunics, the tell-tale scarves exchanged for matching Red Cross caps, but Edith Wilson and Wendy Trevor are not after all sisters-under-the-skin, and their closeness will be the first casualty of peace in Priory Dean.

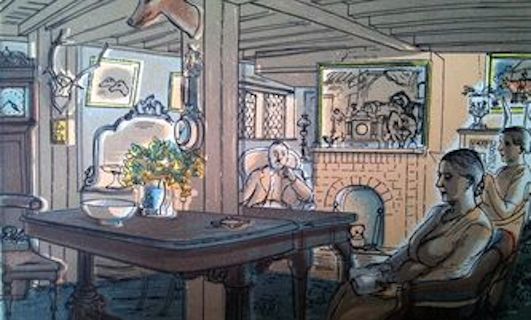

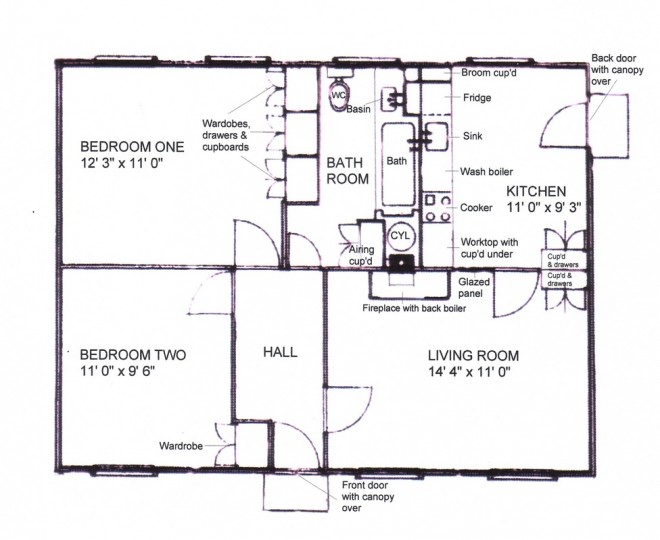

Before the war, in the 1930s, when her husband was ‘stood off’, Edith had cleaned, and washed and cooked for the Trevors, but not living-in as she had in her first position in 1918. The Wilsons have their own (rented) house in Station Road, down the hill from the Trevors, who live at Wood View, owned, detached and with some (but not nearly enough) land. Wartime shortages and rationing, limiting the usefulness of money, and the prevailing mood of all being ‘in it together’ had levelled things, up to a point – in the Red Cross hut it is Mrs T who offers the village policeman a cup of tea, Mrs W who makes it – but ‘both knew that this breaking down of social barriers was just one of the things you got out of the war, but it couldn’t go on.’ It couldn’t go on, but what neither of them can foresee is that when the barriers go up again, it will be in a different place. ‘After the War’ will not be like ‘Before the War’. Writing to a friend Sylvia Townsend Warner summed it up brilliantly: ‘… the temple of Janus has two doors, and the door for war and the door for peace are equally marked in plain lettering, No Way Back.’

Changes that had been thought of as a consequence of the war, and merely passing, were proving to be lasting, while the newly elected Labour government, welcomed by the returning forces and the working classes, feared and loathed by the middle classes, was introducing more, and yet more fundamental changes. The National Health Service, the Education Act, the Welfare State, all over Britain people like the Wilsons and the Trevors, and the shopkeepers of Priory Dean, and the rich businessmen escaping from London, were enjoying or reluctantly reconciling themselves to the new order.

The War has been good to the Wilsons – ‘the first time in our married life we’ve been quite sure we’re going to be alright and save a little to put by.’ Daughter Edie, released from her factory job, may go back into service, but never to live in, their clever youngest, Maureen, can look forward to university, while Roy, their son, demobbed uninjured will go into a well paid job as a printer. £10 a week, ‘more,’ reflects Wendy Trevor, ‘than we’ve got to live on put together.’ Between 1938 and 1949 wages had risen by 21%, while salaries had declined in real terms by 16%. While the Wilsons’ financial star is in the ascendant, the Trevors’ old money, such as it was, has dwindled almost to nothing.

They are the new poor, but still they cling to their social position, and in this the Wilsons collude, because they too have a rung to which they cling, below the people who live on the hill, and below the shopkeepers, but above the labouring class, subtle nuances imperceptible to the Trevors. The Wilsons are doubtless similarly unaware of the unease generated by the draper’s move ‘up the hill’ (that Miss Moodie turns out to have ‘nice things’, inherited, further confuses her status among the neighbouring gentry), and baffled by the hot/cold reception of the Wetheralls, a manager of ‘some big motor works’ and his American wife, ‘nouveaux riches’ to the village gentry, in their eyes simply rich. Social antennae have only limited reception.

When the new Rector inadvertently snubs the late squire’s daughter (‘the only one of the local gentlefolk who belonged to the village by birth’) by moving the fête from the Hall garden to that of the parvenus at Green Lawns, she must bear the affront uncomforted. ‘It would be truer to say that the Priory Hill people were accepted by Miss Evadne than that she was a member of their set.’ The Rector is from the ‘wrong’ class, the squire’s daughter, who, in spite of everything, sees herself as a cut above the rest of the village, in a set of one, turns out to have threadbare curtains. The correlation between money and class was unravelling. Little wonder that the American newcomer finds herself with a lot to learn.

As a left-thinking Hampstead dwelling Jewish intellectual, Marghanita Laski’s mindset was about as far as could be from that of Priory Dean, but she has a fine grasp of the bizarre niceties of village life, sometimes amusing, unsettling at others. Major Trevor finds Martha Wetherall ‘showy’, Wendy thinks her ‘vulgar’, but sees in her the tantalising promise of introductions for their plain, unmarried daughter, ‘If it was a choice between Margaret hobnobbing with the schoolmaster’s wife or the nouveaux riches, the Wetheralls had it every time.’ With no qualification a suitable job is no easier to find than a suitable mate for a shy girl with no looks. Untainted by her parents’ snobbery and doomed aspirations, Margaret Trevor would be more than happy to work as a cook, but there would be no way of spinning that into acceptability. She must take a dreary clerical job in the local hospital, which her mother can pass off as ‘sort of secretarial’ and which might, but doesn’t, offer the chance of meeting some ‘nice’ people, ‘doctors and so on’. Wendy goes so far as to regret that call-up for girls has come to an end, ‘I’d always had in my mind that if Margaret went into the Services, it might solve the problem of clothes and a job and a husband all at once.’ A longer war would have given her more of a chance. If Laski expected her readers to find this shocking, she would not have expected them to be surprised by Mrs Wilson’s sympathy for the girl’s plight: her own Edie had had plenty of young men to choose from, but for Miss Margaret things were naturally different: her Mr Right must come from the right drawer, and this, both women concur, reduces the field to one, the son of the local doctor, spotty, disagreeable and smug, but neither of them would say so. That the Wilsons and the Trevors might ever find their families joined by marriage occurs to neither of them.

Laski has a sharp pen and brings it down pretty un-forgivingly on Wendy for her blinkered and rigid attitudes, culminating in her pathetic appeal to Margaret to leave Priory Dean when she does marry Roy Wilson, for the sake of her social life, ‘almost all we’ve got left’, not just leave the village but leave the country, and not just leave the country but go to the far side of the world, to Australia (not New Zealand which might have been their first choice because Wendy has a sister there who might learn of the shame!). Laski’s sympathy lies with her working class characters: she does not challenge Edith’s conservative (small ‘c’ – she is one of the Labour voters) beliefs, and admires Maureen with her burgeoning communist ideas. It’s not a dully polemical novel, however, but one laced with humour – I particularly like Miss Porteous, who considers herself broad-minded because as a school mistress she ‘had always prided herself on being able to correct the mispronunciation of “womb” ’ – in which politics and post-war social history live on the page.

Free medicine, state pensions, public housing, the spread of industry, the arrival of television, immigration, emigration will all touch Priory Dean. Doctor Gregory resents the prospect of ‘being ruled by a lot of piddling little clerks without an aitch to their names’, but young mothers will be able to get free advice on their babies’ health; the spread of the paper mills will bring jobs, but spoil the ancient views; Irish labourers will speed the building of homes, but may occupy the much needed pre-fabs (a further blot on the landscape), and what is more turn parts of the village into no go areas at night … plus ça change.

In Little Boy Lost (Persephone Book No. 28) Marghanita Laski used one man’s search for his son life to describe the material deprivations and examine the range and complexity of moral problems to be confronted or ducked in post war, post Occupation, France. The Village brilliantly contextualises and puts faces to the winners and losers in post war Britain. Priory Dean is ‘Every Village’.