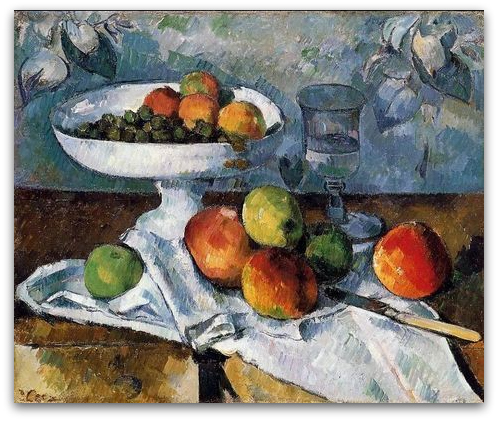

‘… no-one has treated the casual things of daily life with such reverent and penetrating imagination’ … Roger Fry spoke these words in a lecture given at the close of the first Post Impressionist Exhibition arranged by him at the Grafton Gallery in 1910. Fry, who would be a lifelong friend of Virginia Woolf, was speaking of Cézanne. He might have been speaking about Virginia. Woolf’s biographer, Hermione Lee, considers her response to the paintings to have been ‘somewhat sceptical’, but, looking back on the occasion in her biography of Fry (1940), Virginia is clear that ‘something very important was happening’. She had recognised that 1910 marked a turning point, when writers as well as painters would begin to think about new forms. No-one since Chardin, Fry continued, ‘has found as he has, in the statement of their material qualities, a language that passes altogether beyond their actual associations with common use and wont.’

Much, rightly is made, of Virginia Woolf’s decision to use painting as the central image in To the Lighthouse, a painter as a central character, the ‘eyes’ of the novel. Perhaps a better informed Persephone reader can correct me, but I am not aware of any critic thrilling to her decision to see (and hear and smell) through the eyes (ears and nose) of a dog. I don’t know what Roger Fry thought of Flush (can anyone help?), but I like to think of him acknowledging that Virginia had found a ‘language’ as close as could be to that of the Post Impressionists. If Flush makes associations, they are not those that we would make; his wont is not ours. How different the world is viewed from eighteen inches above the ground, and with none of the stale preconceptions that dull our responses. Fry asked that people approach pictures with ‘tense passivity and alert receptiveness’. Oddly enough, one might use just these words to describe the best sort of dog.

Few challenge the view that Flush is a ‘light’ (Virginia’s word) novel, meant she says for ‘a joke with Lytton [Strachey]’, a break after completing The Waves. On 19 December 1932 she wrote in her diary, ‘I shall take up Flush again to cool myself’ (quoted by Frances Spalding in the excellent catalogue to the informative and deeply moving recent exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery). While bemoaning the time spent revising and rewriting it, Virginia frequently dismisses it as that ‘little book’, or ‘that silly book’. That silly book proved a commercial success and a good earner for the Woolfs’ Hogarth Press. But when it was published in 1933 only a few critics praised it, some loathed it (the Granta reviewer predicted the end of a promising literary career), many ignored it, and have by and large continued to do so, affording it only a passing mention between The Waves (1931) and The Years (1937). Only feminist critics have consistently waved the flag for it.

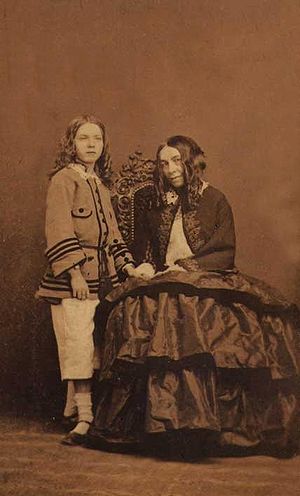

There is a serious message, and we mustn’t forget that Flush, sandwiched between the two great novels, The Waves (1931) and The Years (1937), also lies midway between A Room of One’s Own (1929) and Three Guineas (1938). Confined to her dark, stifling, crowded room by illness and the whim of a domineering (but not unloved) father unable to let go of any of his children (12 in all, of which those who married were disinherited), Elizabeth Barrett in turn, and with similar, unintended selfishness, keeps her little dog close by, so that like her he is ‘cut off from air, light, freedom’, until his limbs are almost as stiff as hers. While his new mistress is metaphorically chained to the sofa, her spaniel, lately running free in the fields of Berkshire, must be literally chained for his daily walks along the asphalt paths of Regent’s Park. Having fathered a pup in his rural youth, Flush is emasculated by the over-upholstered, stuffy Wimpole Street sitting room; the one time hunting dog is fed with a silver fork and drinks from a porcelain bowl. If, occasionally he ran to the door on hearing another dog, ‘when Miss Barrett called him back, when she laid her hand on his collar, he could not deny that another feeling, urgent, contradictory, disagreeable – he did not know what to call it or why he obeyed it – restrained him.’

A dog could be tamed, like a Victorian woman, entrapped in silken skeins, of love and duty, even the most spirited, most aristocratic of dogs, even successful and respected poetesses. Although not laboured, Virginia Woolf’s feminism is never far below the surface, too far for some, who have criticised her for relegating the life story of Miss Barrett’s loyal maid Lily Wilson to a footnote: but it is a very long footnote, comically long, revealing more about the life of a servant than many employers even knew, and in any case the footnotes are hardly footnotes at all, but rather a series of asides.

Her social commentary is acute, sometimes angry. The upper class obsession with ancestry is roundly mocked in the opening pages charting Flush’s pedigree back into the mists of time. She does not contain her outrage concerning the appalling slums a stone’s throw from Bloomsbury, only cleared in her lifetime: the Rookeries, behind St Giles’ Circus, according to Peter Ackroyd ‘embodied the worst living conditions in all of London’s history’ – conditions actually little different from those in which Flush finds himself when he is kidnapped.

But above all Flush is light and witty, and though she hated the prospect of readers describing it as charming, I defy anyone who has ever owned and loved a dog not to be charmed, seduced, convinced by the dogginess. Anyone who has walked with a dog and waited while they sniff, and sniff will be aware that beneath our feet is a world of delights which, with our rudimentary noses, we can never know. Nor do we have ‘more than two words and one half for what we smell.’ The scents of the city are quite as beguiling, more complex, than country ones: for all that Flush was to all intents and purposes like his mistress a prisoner in Wimpole Street, for a creature with a good nose life was never dull.

But the smells of London, though interesting, were as nothing compared to the Florentine richness that Flush would discover later on, when both he and Miss Barrett enjoyed the happiest years of their lives, and the most free. In two pages, Virginia Woolf writes a virtual Baedeker for dogs, describing in sensuous detail the attractions likely to appeal to the four legged visitor: wine, leather, garlic, grapes, incense and more. And Florence, it seems, is also a delight to the paws with its ‘marmoreal smoothness’, ‘gritty and cobble roughness’; the sensitive pads of the canine connoisseur will also appreciate ‘the clear stamp of proud Latin inscriptions.’ This is Italy as we can never know it.

Nor can we hear a distant footfall and reliably distinguish the friendly step from the unfriendly, or accurately guess from the first sound of a broom at what time visitors are expected. Individual words are redundant when tone of voice is all a dog needs to interpret emotions. Hearing Miss Barrett and Mr Browning as they ‘cooed and clucked’ suffices to inflame Flush’s jealousy. Some American academics have, incidentally, recently published in a respected journal a long article, liberally scattered with symbols and formulae and graphs, proving that dogs are significantly more jealous when their human engages with another human, than when she reads a book, or (very American this) talks to a Halloween pumpkin … If dogs could laugh!

So, our human noses and ears are no match for those of a dog; our eyes serve us well enough, but few are able to appreciate objects for their appearance and not their function. On his first trip to Oxford Street, Flush ‘saw houses made almost entirely of glass. He saw windows laced across with glittering streamers; heaped with gleaming mounds of pink, purple, yellow, rose… He entered mysterious arcades filmed with clouds and webs of tinted gauze …’ Later he watched Miss Barrett’s fingers ‘forever crossing a white page with a straight stick and longed for the time when he too should blacken paper as she did.’ In a supreme example of showing, rather than telling, the reader is invited to see as a dog sees. We can then, with a (condescending?) smile, congratulate ourselves on guessing correctly what the humans are doing . Miss Barrett and Wilson disappear for a while and when Miss B returns, Flush notices a gold band shining on her hand, watches her slip it off and hide it. Even if we knew nothing of the Barretts of Wimpole Street, we would speculate that a clandestine marriage has taken place. When Miss Barrett, now Mrs Browning and living in Florence is seen to become suddenly busy with a needle, we understand, long before Flush, what to expect.

Much later, as an old dog, sleeping, as dogs do, under a drawing-room table, he is startled to find himself hemmed in by ‘the billowing of skirts and the heaving of trousers’, and the table ‘swaying violently from side to side.’ The reader herself might be puzzled but here the authorial voice takes over, with a witty and cynical account of Victorian spiritualism, the popularity of which is astonishing to most people, and unfathomable to even the cleverest of dogs, which Flush most clearly is, cleverest and bravest, and it has to be said, most charming.

This ‘little book’ is a tiny treasure chest: vignettes of Victorian domestic life, nineteenth century womanhood, an improbable love affair and marriage, glimpses of Italian cities and political turmoil, and above all, although we can only guess at its accuracy, a rare glimpse into the rich inner life of a dog.