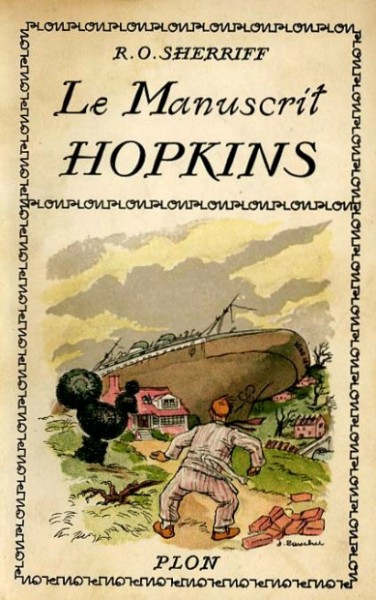

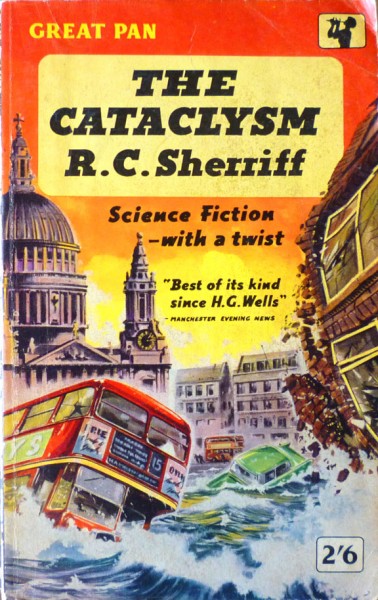

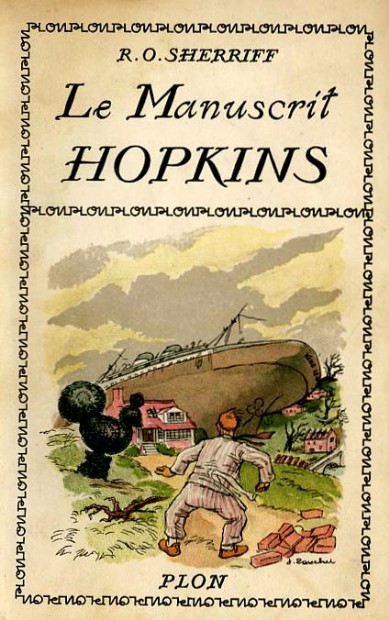

An astonished figure in striped pyjamas and a red beret surveys a scene of rural devastation. In front of his (remarkably unscathed) house stands a large (equally unscathed) topiary cockerel, behind it a vast ocean liner lies on its side. This was the cover of the 1941 edition of Le Manuscrit Hopkins (Sherriff’s fame spread quickly across the Channel). The faintly humorous note was picked up more recently (2009) by another French publisher. On this cover a rather paunchy Nelson looks down on a tidal wave rolling just below his feet. What appears to be a drowned Bonapartist soldier floats by, while a moustached figure holding a clipboard, and presumably frantically treading water, takes notes, with stereotypical Anglo-Saxon sang froid. On his head lies a large white chicken, which is clearly dead. The first English editions were stark by comparison: just the title, a reference to Journey’s End, a ‘puff’ from The Spectator, favourable comparison with H.G. Wells. Only in 1958 in an abridged, re-titled (The Cataclysm) version did The Hopkins Manuscript receive the full ‘Pan’ treatment: a terrifying image of buses and cars swept along in a roaring rush of water which is about to engulf St Paul’s cathedral. No hint of a joke. (By curious coincidence there is an alarming poster currently displayed in the London Underground: floodwater lapping around Big Ben, within inches of the clock, a stark warning of the effects of climate change. No joke there either.)

Pan cut out many of the references to Edgar Hopkins and his Bantams, while the French publishers seem to have relished them. A contemporary Spectator praised The Hopkins Manuscript for ‘its strangeness and suspense’, and also for its ‘equally outstanding humour and character drawing’. Surely it is this, unusual, combination that makes it such an enjoyable, funny, exciting and, yes, moving read: the convincing, if not scientifically accurate (do we mind?), account of a global catastrophe presented by a small man, with a small mind, who nonetheless attains something close to tragic status. For over-weaning self-importance and an almost total inability to see himself as others see him Hopkins rivals Charles Pooter, but I have to admit that I did occasionally feel tears welling as this bumptious, self-centred man slowly and incompletely began to discover his own emotions, to appreciate something of the needs of others, to warm towards his fellow human beings, and to confront the horror of his fate.

We meet him first in a post Apocalyptic London, in between lonely and ever less productive scavenging expeditions, writing his memoirs, by the light of a piece of string soaked in bacon fat. Anticipating a gloomy read, we are immediately reassured by his description of tea with an old lady who has taken up residence in the National Gallery and survives by cooking pigeons on a fire built up from Old Dutch masterpieces. Hopkins, who likes to dot Is and cross Ts, explains that she dislikes Dutch paintings, and ‘enjoys the fire as much as the pigeons’.

The population of London has been reduced to seven hundred people, but Hopkins, showing no false modesty, meets death in the certainty that, unlike the other six hundred and ninety-nine, he will leave behind a document that will one day be valued as highly as the Rosetta Stone, while he will stand amongst the immortals, with Tacitus, Ptolomy and the Venerable Bede.

With astonishing skill Sherriff makes this vain, snobbish individual, with the relentless concern for detail, everything from railway timetables to bridge winnings, of the archetypal club bore, both funny and endearing. He is forty-seven at the start of the events he is recording, not far off in age from Sherriff himself. Hopkins lets slip few details about his past but we pick up that his childhood was happy, that like Sherriff he fought in the 1914-18 war and that he has spent some miserable years after Cambridge as an assistant arithmetic master – the job description is precise and rather sad – Sherriff had wanted to be a games master, and went to Oxford in his thirties the better to fulfil this ambition! Like his creator, although with no interludes writing successful Hollywood scripts, he lives a quiet life, unmarried, in a small village. Though he confesses to being no politician, having ‘always preferred to leave politics to those who had no poultry’, he proves to hold strong, and quite radical views, which may reflect Sherriff’s. He has inherited a small legacy, and once went on a cruise to the Canary Islands, for which he purchased a suit, which he wears on special occasions. He has a stamp collection, a good cellar, unrivalled expertise in poultry rearing and few friends, which given the hauteur with which he treats his fellow villagers and his tendency to bear grudges is not surprising.

So far so semi autobiographical – the life that Sherriff might have led? What shifts The Hopkins Manuscript right out of the genre of English social comedy into the realms of end-of-world science fiction is Hopkins’ membership of the British Lunar Society, at whose Extraordinary meeting he learns that the moon will shortly be colliding with the Earth, information to which only members are privy, and which must be kept from the wider public until the government sees fit to order preparations. For a man already imbued with a hefty measure of self-importance what could be more gratifying than to have a really important, world class piece of knowledge to keep to himself? And meanwhile life must appear carry on as normal.

‘Kilnsey Show’ by Joseph Baker Fountain. Mercer Art Gallery, Harrogate

There are some blissfully comic set pieces, more than one featuring the cut throat world of the Widgeley poultry show, the possible cancellation of which, in Hopkins unusually calibrated scale of importance, is equal in weight to the approaching end of the world. A disastrous exercise in topiary, where a last minute (last days) decision to alter a sitting hen into a gamecock ends in ‘the disappointing result of a small fat man, with his trouser legs turned up, paddling in the sea’, is ‘redeemed’ by a most successful bridge party, recalled seven years later (and for posterity) in gloriously redundant detail. The Spectator reviewer was right too about the characters, mostly remembered by Hopkins for the various minor ways in which they caused him major offence: he expresses no regret at their most unfortunate end. If he misses anyone it is his London aunt and uncle, a jolly theatre-going pair in their seventies, ‘connoisseurs of happiness’ (what a brilliant phrase), whose claims to fame he proudly records: ‘During his [Uncle Henry] prime he did much to add dignity and decorum to the public spaces of London, and it was through his untiring endeavours that the hands which pointed to the public conveniences in Hyde Park had a short length of sleeve and white cuffs painted onto their naked wrists. Aunt Rose had grown stout in recent years, but she possessed the finest collection in England of old coloured prints of stage-coaches that had overturned in snowdrifts.’

Thanks to the time shifts in the novel, we know right from the start that life of a sort continues after the cataclysm, but turn the pages rapidly to discover who survives and how and where. There is a poignancy in the waiting: lyrical passages describe burgeoning spring flowers, and innocent nesting birds and, once the order goes out to prepare, a new sense of community develops and social barriers begin to break down as shelter digging parties are formed – Hopkins is ‘almost tempted to tell John Briggs, the carpenter, that my Christian name was Edgar’, but resists the temptation. New friendships are forged. Edgar, having late in life recognised his loneliness, tentatively and awkwardly accepts the overtures of the family at the Manor House; the reader understands more clearly than he does himself his feeling for twenty-year-old Pat, and her younger brother Robin. To all three Parkers on the night of the moon crash he bids a sad farewell, ‘my last meeting with three people whom I loved’. The prospect of catastrophe has been an emotional epiphany for Edgar.

!['... he [Robin] was in the library persuading me to go across to the Manor House with him to fetch his portable gramophone and a pile of records.'](https://persephonebooks.flywheelsites.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/french-gramaphone-ad-1930.jpg)

Michael Moorcock explains in the Introduction, ‘We write such books [science-fiction] not because we are convinced that they describe the future, but because we hope they do not.’ ‘The terrors of [the moon’s] arrival,’ warns Hopkins, ‘were trivial beside the horrors that it held in store for us.’ There are horrors to come but, and this is the most charming and uplifting section of the novel, for two short years the little band of survivors enjoy a magical ‘Epoch of Recovery’, ‘a precious span of happiness that nestled between cataclysm and final disaster.’ At first the resourceful little group, Pat, Robin and Edgar, with one old retainer, who lives in the apple store, because he prefers it that way (and so does Edgar) make do on their own in what remains of their village, eventually finding their way to the small local town, considerably smaller since the cataclysm – from a population of 3000, Hopkins makes a precise, and seemingly unconcerned note (the experience has not made him noticeably more sensitive to human tragedy), 436 have survived. All have jobs, and Mulcaster is able to rebuild itself according to sound nineteenth century principles, allotting half an acre to each house, no more ticky tacky little boxes. This is a golden age, a Utopia of self-sufficiency, co-operation, of old-fashioned values and a reliance on individual skills and crafts, where barter has replaced money and the true value of things is established. Fair shares for all.

From the first inklings of the impending catastrophe, small communities had coped better than cities: while the sturdy villagers of Beadle dug shelters, organised sing-songs and arranged moonlight cricket matches, London’s prisons filled with lunatics and the river with suicides. Post cataclysm, for a while, the new ethos seems about to embrace not only the villages, but cities and even the entire continent. ‘From the ashes had risen the United States of Europe.’ Has the human race, Europe at any rate, been given a second chance? Hopkins has told us it can’t last. The ‘final disaster’ is not altogether surprising, and bizarrely prescient.

And is there just a glimmer of hope for Edgar on the last page?

![‘He [Brian] thought he ought to see something of them every day, since their mother saw so little. He read aloud to them at this time. Not that they cared for it, but he thought they ought to. ... At the moment he was reading the Just So Stories.’](https://persephonebooks.flywheelsites.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/JustSoStories-1st-edition-1902.jpg)