‘So many fairies had attended her christening … and in the end they had all dwindled to such a sad and joyless measure.’

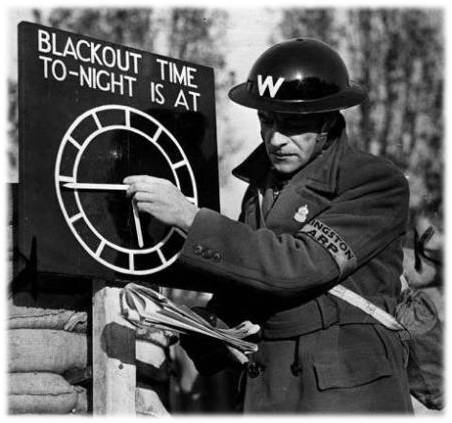

Reflecting on the life of his patient, Claire Temple, now in her eighties, her doctor lists the gifts brought by the fairies: imagination, personal charm, grace of bearing and a most uncommon vivacity, gifts which time and encroaching dementia have dulled, so that they are glimpsed only occasionally, like familiar landmarks in the war-time blackout lit by a sudden and fleeting torch beam.

Based on the life of Violet Hunt, a prolific and, in her time, successful author, known for her glittering literary salons, where Ezra Pound, Joseph Conrad, Wyndham Lewis, Henry James and, her long term lover, Ford Maddox Ford rubbed shoulders and exchanged gossip, There Were No Windows opens long after the last guest has left. The fine furniture, is gathering dust like the signed photographs that still line the stairs. Claire whose mind is as dusty as the frames can no longer remember whether the celebrities who signed them are alive or dead, and there are no visitors to admire them. For what then ‘had one taken all the pains one had taken to know people if, at the end there was no-one to impress’? All the ‘qualities’ that she had valued in herself since she was a girl, beauty, charm, wit, even her talent for writing, have become meaningless without an audience. Her life to date has been lived through others (not for others, she is far too selfish), been validated by others, and finally there are no others, none, that is, by whose affirmation she sets any store. ‘… at the end there was no-one to impress’.

Mrs Temple’s books are out of print. Reams of old manuscripts and a silent typewriter in a cold, unused study are all that remain by way of proof of her identity as ‘a woman of letters’. An Irish cook-general, whom she dislikes, despises and fears in almost equal measure, a weekly laundry woman whose name escapes her, to whom she is absent-mindedly (literally) charming, asking four times in a short morning after the health of her husband (dead), a weekly secretary, and latterly a mousy companion make up the household at Campden Hill. There are few callers. She is, as she sees it, alone, apart from her cat. Having all her life sought, and found, stimulus from outside, she finds her situation not only painful, fearful, but extraordinary, ‘because it had happened of all people to Her, a Woman who had known Everybody…’ Dullards, knowing no better, might accept it, ‘sink without murmur into long, lonely senility to the click-clack of their knitting-needles’, but not Her.

Claire’s hauteur is at the same time unattractive and understandable. Who wouldn’t prefer an evening with Henry James or Ezra Pound to one with poor drab humourless Miss Jones, such an uncompanionable companion, whose pleasures are all negative: not being disturbed, having no callers, having no relatives. The perceptive Dr Fairfax sums her up so well: ‘Miss Jones and her like looked out into a world composed of culs-de sac. Theirs was the negation of imagination.’ But he is also right when he adds that, ‘a world without Joneses would be a world without ballast … an inconceivable world.’ Claire is incapable of appreciating their importance. The Joneses, along with everyone else who cares for her, who keep her safe and fed and clean, the servants, and the policemen and the air raid wardens, dull people, to whom one had to ‘speak in words they understood’, are all part of life’s necessary infrastructure, largely indistinguishable one from another. ‘Are you a warden or a policeman?’, does it matter, what’s the difference?

Her treatment of her servants, and everyone else she considers to be her social inferior, shocks us now, perhaps somewhat more than it shocked readers in the 1940s, to whom it may have seemed old-fashioned but not unusual in a woman of her age and class, who had enjoyed her heyday before the First World War. Mrs White, the laundry woman, considers her ‘proper old-fashioned in the way she talks about the lower classes’, but cook, Kathleen, on whom Mrs White looks down because of her Irishness (social lines are drawn at every level), defends her employer on the grounds that she is ‘a lady’. Taken, ill-advisedly, to a public house by an old friend and his son, Claire is quickly recognised as a ‘toff’, but the antagonism is relatively mild, and she doesn’t hear the rough words that follow her ‘gracious’ but inappropriate, ‘Good night. It’s been very pleasant’: ‘After the ruddy war, people who think they own the ruddy earth will have to get off, see?’. The time is coming when a well-spoken pretence of interest in the lives of others – ‘Next time I must ask him about his wife and children. That’s what nice common people prefer.’ – will cut little ice, but she won’t live to see it. Meanwhile she can fall back on the script that she learned long ago.

Having played the part first of the grande amoureuse, and later the Victorian widow (although the marriage to Wallace Temple seems to have been a fiction), much of her life has been and continues to be an act. Her costume is threadbare, she has begun to forget her lines, or, more irritating still to her few remaining friends, to repeat them, and the rest of the cast have left the stage. Her friend and rival, Edith Barlow, unkindly compares Claire to the Red Queen, running to stay in the same place, ‘but her friends had not stayed in the same place: they had moved on, and they had moved away. So when this Red Queen looked round, the once-crowded scene was deserted.’

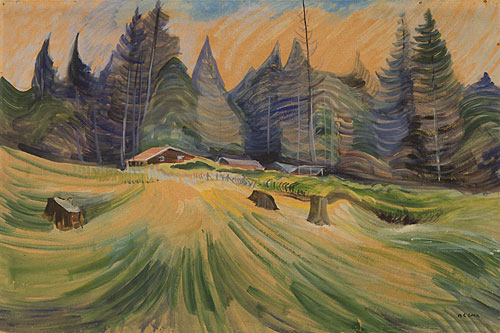

‘When had all the parties to which was asked stopped?’ She couldn’t remember, so it must have been gradual, as gradual as the turn of the tide.’ Self-centredness, self-delusion, self-protection, and finally dementia have to a degree protected her from life’s harsher realities. She needs, but doesn’t want, reminding that there is a war on: ‘Everyone keeps harping on it. Really it’s rather silly to make so much of it.’ The war means a shortage of maids, of cooks and worse still a shortage of men; it means that a bottle of wine costs four-and-six rather than two shillings; it means no cream with one’s pudding. War is pulling the black-out curtains tight together when one wants to look out; finding shop blinds down and doors barred at ten-past-four, women wearing unbecoming trousers, shopping unwrapped. It’s not the fear of bombs or enemy planes – ‘I’m not frightened. Why should I be? I’ve nothing left outside myself to be frightened of’ – nor the jagged gaps where houses, including her mother’s, once stood.

Far worse for Claire is the sudden realisation that the London she had known, the smart tea-shops and taxis and theatres filled with friends, has gone: just for a moment (because she can never look for more than a moment at anything upsetting) she glimpses the ‘abomination of desolation that is all around her’. That same desolation is inside her, just as the terrifying darkness of the streets in which one must find one’s way with only a covered torch (I recall my mother saying that walking at night in London during the war was as close as she could imagine to being blind) parallels the dimming of her mind. This war is a much internal as it is external.

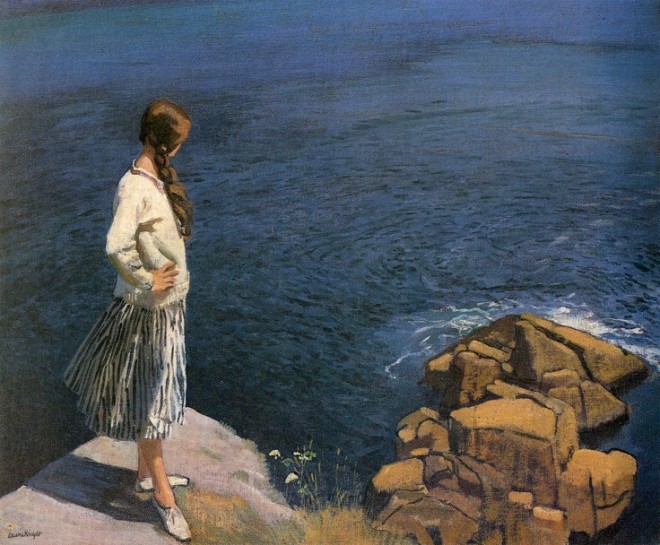

Claire is fighting the loss of her memory, of her past and of her identity, her position in her world, a position, as was the case for most Victorian-born women, that depended on the men around her, father, husbands, lovers. A woman alone risked becoming a nobody, little better than the homeless dosser, outcast, ‘one of the shipwrecked’, ‘living in and to herself’.

In the final section of the novel, as the darkness closes in, Claire berates herself for not following the advice of Henry James, to ‘cultivate loneliness’. But how, indeed why, would she have done that? Her gift was for ensuring that others were amused, for bringing together the brightest of literary minds. How often one reads in obituaries that ‘x had a gift for friendship’, and how very rarely, if ever, that ‘y successfully cultivated loneliness’. The world needs Claires as much as it needs Joneses, but old age suits the Joneses better that it suits the Claires. In one of her moments of clarity, more frightening than the dark, Claire Temple sums up her tragedy, ‘Mostly in my life I have been treated as a monkey because I was entertaining. But now the cage is round me …’

It is a sad story, and a disturbing one because we cannot help but realise that our wits too might – will – stray in time, but it is a compassionate story and leavened with a dry humour.