It is hardly an exaggeration to say that ‘childhood’ began at about the time of Molly Hughes’ birth in 1866. ‘A girl with four brothers older than herself is born under a lucky star,’ she begins. To be born into the middle or upper classes in the 1860s was lucky indeed, brothers or no brothers. These children, though not their poorer contemporaries, could grow up in the expectation that for a few years they might be spared the harshness of the adult world. This would be their ‘golden age’, a period of enjoyment, of education without responsibility. The Victorians did not invent childhood, but they did elevate it to a state of grace, one from which by definition a growing girl or boy must eventually be cast out.

I was taught (by an aunt who had, like Molly, been brought up in the conviction that she was lucky) to be nostalgic about childhood even before I had left it. I loved to hear her recite Victorian poetry to me: among her (and my) favourites, was Thomas Hood’s ‘I remember, I remember’ – she would drop her voice when she came to ‘My spirit flew in feathers then / That is so heavy now’ and barely whisper the last lines, ‘But now ‘tis little joy/ To know I’m further off from Heaven/ Than when I was a boy’.

Molly Hughes is quite open from the first two short paragraphs of A London Child of the 1870s: for the first twelve years of her life, her spirit, like Hood’s, ‘flew in feathers’, until in 1879 something happened to bring an end to her happy childhood. This unspecified shadow hangs over each joyfully recalled episode. But how cleverly she keeps us waiting, forgetting in the innocent bliss of the moment that this cannot last, then remembering and wondering where the blow will fall. When it does come, it is as the Americans say, from out of left field.

‘We were,’ writes Molly in her brief preface, ‘just an ordinary, suburban, Victorian family, undistinguished ourselves and unacquainted with distinguished people’, which may have been how the Thomases appeared to their Canonbury neighbours, and to their children at the time, but is not entirely accurate. The family that Molly describes was not ordinary, nor were their acquaintances undistinguished. The grown-up who bowls to the boys in the garden was no village cricketer: Charles Absalom played for England. The doctor who offers informal advice to Mrs Thomas over tea, was not some local GP, but Sir William Gull, Physician-in-Ordinary to Queen Victoria.

If the adjective ‘Bohemian’ was common parlance in 1870s Canonbury, it would surely have been applied to Molly’s parents. Her father worked at the Stock Exchange, but was no staid city broker. The family fortunes wavered between ‘great affluence and extreme poverty’. She would have us believe that the children were unaware of ‘ups and downs’ but that cannot be quite true, since she also recalls times when the gas was cut off and years so lean that they were ‘devoid of servants’. More downs than ups maybe. Though he may have been unreliable as a breadwinner, as an ‘instigator of larks’, her father shone: kitchen larks – toffee and welsh-rarebits, a feast of sprats on a bare table, river walks alongside Kew Gardens (too expensive even then to pass the gates), hide and seek in Epping Forest, the Agricultural Hall, Crystal Palace, the Tower of London, these outings being for the boys only – shocking for the 21st century parent, but Molly generously forgives him the sexist prejudices of his age. They mother, from a prosperous Cornish family, well educated for the period, well-travelled and an accomplished chess-player, ‘never bothered to alter attire for anyone’ (even the Cornish relations changed when entertaining visitors to tea); preferred to stand while sewing, because she hated it so; and was sufficiently relaxed about her daughter’s education to carry on with her own water-colours while Molly learnt French poetry, or to cancel a morning’s lessons for a shopping trip, a sketching expedition to Hampstead, or a visit to the National Gallery.

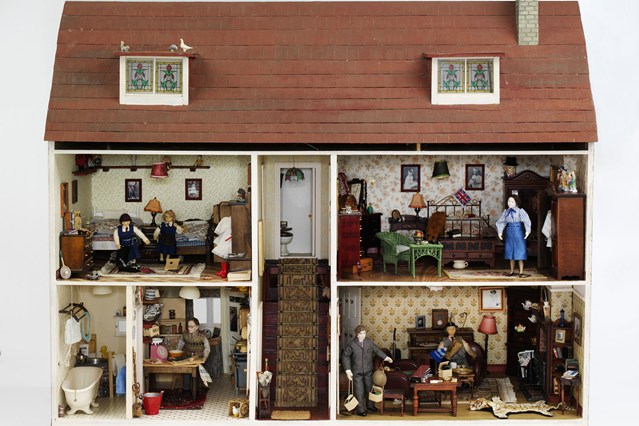

For all their newly enhanced status, children then were generally still expected to be seen rather than heard, and for fear of the consequences the rod was not spared. But the Thomas household was different: both parents adopted, deliberately, from necessity, exhaustion or simple selfishness, a somewhat laissez-faire attitude to life and to education. Only two rules were laid down, ‘no complaints’ and ‘never be rude to servants’, with one addendum, that they were never to take their mother’s scissors for their ‘private ends’. There seems to have been no rod in the house (although her brother Barnholt, the youngest of the four, testified with pain and rage to its frequent use at school), and if the children were not seen, it was because they had their own large room in the house, NOT the conventional nursery (there was no nursemaid) but a room they called ‘the study’, in which the few toys were for the most part plain, and well past their best: the soldiers were ‘wounded and disarmed’ and chessmen dressed in velvet and armed with cardboard stood in for Arthurian knights.

In more affluent households, the 19th century market economy had found a new group of consumers. Factory owners – maybe ironically the same factories that had begun to draw in child labour from the country – were quick to respond to the call for toys to delight the recently enthroned princes and princesses of the nursery. Games, dolls and dolls’ houses were soon being mass-produced, for those whose parents could afford them, but for the Thomas children, ‘a new toy was an event’ and sixty years on, Molly vividly remembers the thrill of receiving a ‘resplendent horse and cart’, and later a magic lantern.

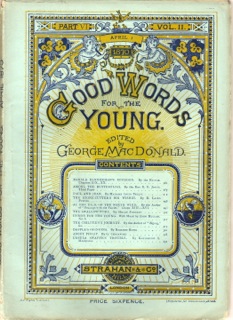

But Tom, Vivian, Charles, Barnholt and Molly were rich in another way. Their parents had books. At first a room for carefully shelved treasures, a geometry set, a magnifying glass, paints and pebbles, ‘the study’ slowly evolved to mirror the house beyond, becoming a library (for which the children drew up a quantity of rules, far exceeding those imposed on their general behaviour) and the editorial hub of a family magazine. Publishers too had spotted a gap in the market, and by the 1870s ever more books appeared, written to delight children, and not, as previously, purely for their edification. Amongst her own books, Molly lists Alice in Wonderland (in English and in French!), Alice Through the Looking Glass, The Little Gypsy and Little Rosy’s Voyage Round the World, all published between 1865 and 1871 and she may well have read some of the more ‘home-centred’ works of Juliana Ewing and Mary Louisa Molesworth, featuring middle-class nursery life in all its richness: hobbies, games, theatricals – the very life that Molly describes, and which remained the stuff of story books, well into the twentieth century.

But there was another dimension to the Thomas childhood, even more wonderful: the Cornish holidays. Molly calls them ‘the happiest days’ of her life, a measure of how happy they were being that, although they lasted for no more than a month each year, they occupy almost a third of the memoir. These holidays were spent with their mother’s extended, very extended, family, whose child-rearing philosophy, with the exception of one or two aunts ‘of the severe type’, was of the same benign neglect school as her own. The words, ‘grown-up people know best’ were never heard. ‘Our fearlessness,’ Molly explains, ‘was our safety’, scrambling down uneven paths to the beach, jumping into rock pools, perching on high barn beams, or picnicking in trees. Remarkably, although Molly does not seem to think it so, no bathing bag, or picnic basket was complete without books.

‘Above a Cove, North Cornwall’ by Arthur Hughes. 1889.

Molly’s descriptions of ‘jollity and enjoyment’ are full of such particular delights, but she has too a gift for bringing the mundane vividly to life, adding everyday details that few contemporary novelists or even mémoirists would mention. Their readers would not need telling about street hawkers, or London milk-maids with buckets hung from yokes across their shoulders; they would be familiar with straw on the floors of omnibuses, sand on the floor of inns; a horse slipping on wet cobbles and being pulled up from his high seat by the driver of the hansom cab would hardly be worth mentioning. Women would know, to their discomfort, that big London shops had neither restaurants nor toilets. Molly tells us all this. She describes the thrill for a child of being taken by her brothers on top of a bus, outside with the driver ( I can remember as a child London bus conductors still, puzzlingly, telling passengers that they would find seats ‘outside’ ).

We might expect that the train journey to Cornwall should be an adventure, but that a train in those days was never ‘on-time’ comes as a surprise, as does the need to takes all one’s own food and drink, and the relief of a predictable ten minute stop at Swindon, whose station, unusually, had a refreshment room. And, looking through a child’s eyes, we can appreciate both the tedium and the excitements of the long Sunday walk from Canonbury to St Paul’s Cathedral, quicker than the horse-drawn tram – could we have guessed that?

Childish misunderstandings delight: when her mother refers to Queen Victoria as ‘having walked on the edge of a sword’, or the congregation is called upon to ‘magnify the Lord’, little Molly pictures the queen’s feet cut to ribbons, and sees a new use for her brother’s magnifying glass. Understanding, when it dawns, particularly when it is associated with the emotions of grown-ups, is not always comfortable. Hyper-religious Aunt Lizzie, who had run away to marry, only to find that her husband was a violent drunkard, and who, having left him, must live by giving music lessons, arouses fear and amusement in the children, and pity among the relations. Only much later does Molly consider the possibility that ‘Lizzie’s extreme piety may have driven her husband to drink and extreme measures’. Beloved Tony, the ‘golden aunt’ (who arrives one day unexpectedly to stay, bringing with her a barrel of apples and a pig), forgiving an untidy house, observes that ‘where there is no ox, the stall is clean.’ ‘As a child,’ Molly adds, ‘I thought this a funny remark, but now it seems quite otherwise.’ The same aunt, whose fiancé had died years before, wrote to Molly before her death that she could never thank God for creating her: ‘I understood then,’ she writes, ‘how much a woman could hide.’ So we get clues as to the writer’s life after 1879, when the child had so abruptly to give way to the young adult. Never judgmental about her parents, she concedes that ‘this happy-go-lucky attitude may be immoral from one point of view, but I have found it an excellent preparation for the continual uncertainties of my life.’

Sixty years on Molly still has her childhood books, her brothers’ complete works of Shakespeare, pristine copies of the family magazine, even some of the notes exchanged by string and window post between the siblings, and a firmly held belief, common to every generation (though by no means every class in society), that yesterday’s childhood was somehow better than today’s. An unhealthy attachment to the past? Confirmation that there once was a ‘golden age’? A yearning to return to a ‘lost domain’? Or simply a reminder that a happy, loving, easy-going childhood, with modest possessions, is a better preparation for life than one which is either over-regimented or over-provided, or both. This short, but very definitely not slight book, makes a powerful statement about values, and possessions, about the importance of living every moment, and about making one’s luck.