‘… Inhibited and handicapped by caste, … too proud to beg, too inexperienced to live upon their wits in a competitive age’: in her 1939 memoir, Passionate Kensington, Rachel Ferguson offers an explanation for the plight of the impoverished gentlewomen.‘whose terrible needs every government overlooks, being apparently unable to visualize an empty larder and a coal-less grate as a condition of life suffered by any class above the labouring one.’ In Alas, Poor Lady, she tracks one downward spiral from a comfortable upper-middle class nursery, in a large Kensington house with six servants, and a butcher’s bill of £60 a quarter (a governess might expect £50 a year, a nursery maid £12), to a furnished room in Pimlico where tea must be frugally measured, and soap is a luxury.

Alas, Poor Lady opens in 1936, with Miss Scrimgeour and a certain Lady Mell gratefully receiving annuities from an underfunded and, unsurprisingly, unfashionable charity, ‘The Distressed Gentlefolks’ Protective Association’, clearly modeled on the Distresssed Gentlefolks’ Aid Association, founded in 1897 by Elizabeth Finn and her daughter Constance, shocked at finding one of their friends, an unwanted poor relation, virtually destitute. ‘How does is it happen? How does it happen?’ Rachel Ferguson asks the question in the opening chapter, and shows us how, and why, and where the blame might lie. Her answer is subtle and complex, and leads towards the conclusion which she draws in her later memoir, which, though it might shock, should not surprise us, that ‘the continuity of this neglect is made possible by the victims themselves’. This is a sad novel but it is not sentimental. Ferguson is a close observer of social mores, exposing the flaws with an acerbic wit, skilfully wrapping mordant criticism in such elegant phrasing, that some of her sentences only reveal their full force on second reading.

Grace Scrimgeour is, without question, handicapped by caste. Born in 1870, she is the eighth child, the seventh daughter (a son had died at birth some years earlier) of upper-middle class parents, Captain Charles Scrimgeour and Charlotte, whose youthful attractiveness has been greatly diminished by too many pregnancies. Charlotte is silly and indecisive, or more probably ill-educated and denied the chance ever to make any significant decisions, even those concerning her own body: her husband’s desire for a son will prevail over her reluctance to bear any more children. This is a patriarchal society, the will of the patriarch is paramount, and the necessity for there to be a patriarch in waiting is not questioned. The caste requires that there be a son and heir, and takes no account either of the human cost, or the economic cost. A mother’s health can be broken, the self-esteem of unwanted daughters utterly diminished, and the family coffers drained, for even unwanted daughters must be fed, clothed and given some education. On that front poor Grace suffers more than her older sisters: they have been sent to school, but she must make do with a bored and boring governess, to save money for the education of her younger brother, the longed for son, a frail late arrival, who nearly costs his mother her life and for whom no expense will be spared – the rocking horse, the pony, the gun, public school, Sandhurst, the regiment, even the sowing of wild oats must be budgeted for. Aware of the inequality, Grace dare not challenge it, dimly conscious that to do so might jeopardise what little affection her mother has remaining for her. She senses quite early that ‘everything they [men and even younger brothers] did and had seemed to be more important than anything one did, or one’s sisters did’, and her first inklings prove correct. She will learn, like her sisters, that, while a man might fill his life to the brim, ‘A woman’s life was one of eternal waiting, to be taken out, called on, danced with or proposed to.’ And ask the same question, ‘How had it originated this division of opportunity?’

But the caste makes victims of all who belong to it, men as well as women. As children boys must put away any toys that might be considered girlish, as young men they cannot enjoy the friendship of women of their own class. Charles, the long desired only son, finds friendship, laughter and sympathy with Ruby, a Soho ‘daughter of joy’, who shows him that speech could be ‘original and not dictated by the taboos of home or the herd-utterance’, ‘who exercised mind and body fearlessly, as they should be and apparently they never could or would be in South Kensington’, and who notices when he looks tired. Yet to his shame he knows that if he met a sister while in Ruby’s company, ‘he would cut her, or leave Ruby humbly stranded, while he kept in play the bore that was the woman the world considered it could still respect.’

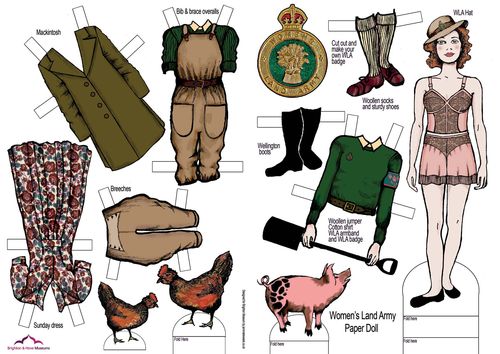

Fathers must provide lavishly for their sons until they leave home, and their daughters must be launched, expensively, into society – the marriage stall. If successfully disposed of they will require dowries, which will, perfectly legally, be appropriated by their husbands. It was a buyer’s market -by 1910 women in England would outnumber men by over half a million, a figure that was about to increase dramatically – and if they should fail to meet its exacting requirements convention dictated that they remain at home, where, since convention further stipulated that young women of the upper and upper-middle classes should not seek employment, they would need supporting until they married, or died.

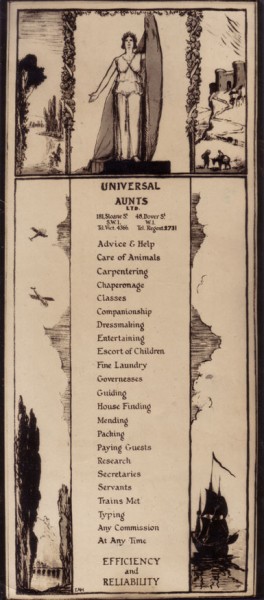

‘Daughters, confound ‘em’, says the Captain, ‘were a problem, God bless ‘em, and bad investments, too, because you couldn’t plan for them’. To have four unmarried daughters at home is annoyingly expensive for the Captain – no return on investments and an ongoing drain on resources. It is disappointing, even shaming, for Mrs. Scrimgeour, and cruelly infantilizing for the girls themselves. Even the nursery maid on £12 a year is free to go out and meet her friends, without the need for an escort or a chaperone; her work is hard, the hours long, but her meager wages are hers. Mary and Queenie, Agatha and Grace have no money of their own, to go out alone would be unseemly, and have so little to do, that they compete for the few menial morning tasks: cleaning out the canaries, writing notes of acceptance, doing the flowers. Mary, the oldest, and plainest (she has ‘the Scrimgeour nose, but does her father take the blame?) of the home-bound girls, is well-read, good with figures – she is allowed to check, but not query, her mother’s household accounts – and witty (an adorable feature in a four-year-old boy, but a damnable characteristic in a woman); ‘she had a brain and she knew it, a brain that functioned clearly enough to make home like unsatisfactory without suggesting a solution’. For years she carries in her pocket a photograph cut from a newspaper of a group of Newnham girls.

The idea that she might take on the teaching of Grace and little Charlie is furiously dismissed by her father, almost as furiously as her sister Queenie’s proposal some time later of setting up a needlework shop. An earlier, fanciful, dream of Cambridge, generously suggested by the much cleverer Mary, had met with a similar reaction, worse even than her sister Agatha’s decision to enter a convent. ‘… being a nun “showed” rather to one’s world, but not so badly as being a bluestocking.’

Captain and Mrs. Scrimgeour are unthinking adherents to the caste rules. They do not question or challenge ‘the taboos of home’, nor do they expect to be questioned or challenged. With masterly understatement Rachel Ferguson describes Mrs. Scrimgeour as having an ‘inelastic mind’, and ‘for evasion a talent approaching genius’. Grace’s three married sisters knew nothing of sex or childbirth as they went to the altar, and none of the girls think it unnatural ‘that they never saw their own basement any more than it occurred to them to wonder where, Tom, the knife-boy slept, which was in a pantry, on a camp-bed that had belonged to their father’. Ferguson is gloriously oblique in her criticism, but leaves the reader in no doubt that had they ventured into the kitchen in their youth, and observed the preparation of the food that was carried up to their table daily, it might have stood them in good stead in later years, when there would no longer be a pantry or a basement or a knife-boy. And, just as importantly, they would have learnt how the other half of their own household lived.

Married at seventeen, in the mid 1840s, Charlotte had gone from her honeymoon to the house in Brecknock Gardens, staffed and furnished for her by her mother, who, while giving her no instruction in the ‘baser’ aspects of marriage, had acquainted her fully with the unwritten caste rule book, ensuring that she, and her husband, would adhere rigidly to the social conventions of the mid-nineteenth century, until well into the twentieth. With conspicuous lack of success, and near tragic consequences for their youngest, Grace, the ‘Poor Lady’ of the title, the Scrimgeours endeavour to crush their daughters into their own outdated mould. Rachel Ferguson makes it clear that all of them suffer, but leaves us to weigh up which of them suffers the most. Is it Arabella, whose husband is unfaithful, or Gertrude, equally unhappily married, but more outspoken – ‘the tendency is … for us to withhold information, and let the next lot enjoy the same disillusionments in the approved manner’? Is it Agatha, whose postulant dreams culminate in a short and miserable life as a teaching nun, as Gertie knew they would: ‘Aggie’s fallen in love with the trimmings … she calls it religion but with her it’s really haberdashery’? Is it the frustrated intellectual, Mary, who would happily forego marriage for a friend with whom to share her delight in books, or Queenie, whose early ambitions for a career, unconcealed, put paid to her chances of marriage? Or Grace, who, with neither brains nor beauty, but a sweet nature, ‘quite simply wanted home and love, romance and frivolity’, which she has been deluded into thinking of as her ‘womanly rights’ and which will all be denied her.

Rachel Ferguson sums up the plight of the young Victorian with acid precision and poignancy; ‘Girls like Queenie [and Grace] were being brought up tacitly for marriage, but the business faltered and stopped at assumption, was neither honest nor sensible enough, having postulated her destiny, to fit her for it in any way whatsoever. Whether she won depended on side issues, matters of looks, dash, charm, brains or personality with which nature, always unreliable, might or might not have equipped her.’ Nature had failed Grace on all counts, and further, being the youngest, she faced more years of poverty than her older sisters, as the family funds diminished, increasingly rapidly, plundered by her father, squandered on ‘good causes’ and her own comfort and pride by her financially illiterate mother. An acute, un-cowed, bank manager sums it up: ‘the imperilment of the future of three women [the remaining spinster daughters] through a mother’s financial imbecility and a law which made it possible’. Mrs Scrimgeour’s old-fashioned, worthy but unsustainable loyalty to her staff, results in the children’s nanny being far better cared for in old age than Grace or her sisters. Even Tom, the knife-boy, who as a lad shockingly escaped all blame for impregnating the nursery maid – ‘these sort of things were nearly always the girl’s fault’ – is pensioned off with £30 a year, having ‘only semi-skilled and outdated labour to offer. The whole household is perilously locked in the same time warp.

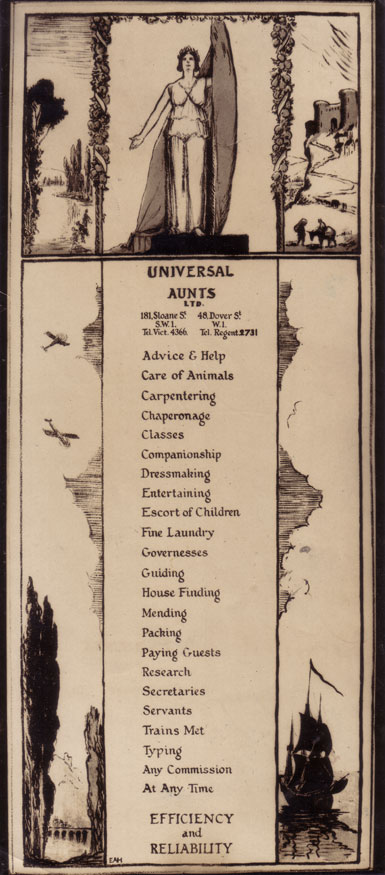

The next generation are already doing things differently. Grace’s niece Paula, having turned down two offers of marriage is running her own dance school. Only eighteen months older than her aunt, and ‘no flapper’, Gertrude’s daughter has been given some proper preparation for life. But at forty, Grace is not even semi-skilled, and of a type, as Paula recognises, ‘that got itself overlooked because it wouldn’t push itself forward and hadn’t any physical façade if it could.’ Her dancing years are long past, the hoped for babies will never come. Favouring showing over telling, Ferguson invites us to infer the moment of her menopause: ‘When, at the Tarrants, she knew beyond doubt and evasion that even if she should marry, the union would be a childless one…’. Her married sisters and their children provide some support and from time to time, when needed, a roof, in exchange for genteel errands, shopping for school uniform, taking a child to dancing lessons, darning … employment (unpaid) for the maiden aunt.

‘In a competitive age’, no more qualified than her own despised governess, Miss Banks, thirty years earlier, she finds herself moving, with pitiful luggage, from family to family, trudging, in failing health between employment agencies, where her honest upbringing will not allow her to lie about her age.

Two pieces of luck bring a little light to the end of the still childlike old lady, the second of which I won’t reveal. The first is the annuity announced in the opening chapter, a similar grant being made to a certain Lady Mell, the same Lady Mell from whose estate the Scrimgeours were used each year to receiving a Christmas tree. Lady Mell’s fall from riches to rags would have made another story, and so, possibly, in years to come might the lives of the ‘earnest-unmarried’ daughters of the prosperous women gracing the bazaar, another generation of ‘superfluous women’.