“Oh, I do wish she’d been a doll!” Young, beautiful, selfish and shallow, Eleanor Conway finds herself reluctantly charged with her husband’s niece and nephew. Neither is welcome – she doesn’t like any children much – but seven-year old Teddy, fair and golden-haired, will do very well as an accessory for a committed socialite. Not so his little sister, five-year old Babs, dark, square and sunburnt: ‘an awfully plain, rough, wild little creature’ warns Eleanor’s equally selfish husband Charley, who has himself barely overcome his initial astonishment on finding his new wards to be “little men and women” and not, as he had somehow expected, ‘big dolls’. While the children, the ‘young pretenders’ of the title, breathe life into their nursery toys, Captain and Mrs Conway struggle to contain the small flesh and blood creatures who have been thrust upon them, awaiting the uncertain return of their parents from India.

Edith Henrietta Fowler reminds us that what children need is love, and that shared genes are neither a prerequisite nor a guarantee of that. Published in 1895, when so many parents were away in distant parts of the Empire, and so many children brought up by grandmothers, previously unknown relations and old retainers, The Young Pretenders must surely have touched a nerve in many a young reader. A happy childhood in loving surroundings was far from assured for these temporary orphans. For the lucky ones a devoted nanny, a friendly gardener, a jolly young governess, a nursery full of cousins or an uncle with a sense of fun must have made all the difference.

Most loved in Babs’ small world, are her brother, Teddy, Nana, her nurse, Giles, the gardener, and ‘Father-and-Mother-in-Inja’; the mispronunciation makes us smile, the hyphenation makes us weep for a child, who has never known either her father or her mother, for whom the two have fused into one parental cipher, geographically and emotionally remote. Grannie Conway, in whose ‘care’ (hardly that) Teddy and Babs had been left when she was a year old and her brother three, was old and frail and indifferent to her grandchildren. She does not feature in the short list of best beloveds and is not mourned when she dies, though her death precipitates Babs’ expulsion from their rural paradise to ‘the new, narrow life which she was to live in the sunless atmosphere of her uncle and aunt’s selfish life.’

The Young Pretenders is essentially Babs’ story, covering barely six months, no time for the grown-ups, but a tenth of her little life, told largely in her voice and often in her words. To the twenty-first century adult reader (though not, I imagine, to the younger reader for whom the book was intended) some of these can sound a trifle twee, but Fowler makes brilliant use of ‘free indirect speech’ (to borrow the language of lit crit) in a way which is both amusing and moving, eliciting a knowing smile, and from time to time triggering a sad tear of sympathy, when the child’s words convey so more than she herself can understand.

The children, Babs especially, are painted in full colour, the grown-ups, seen largely through the children’s eyes, appear as dot-to-dot drawings. Only by joining the dots, incidents observed, snippets of conversation overheard, words inaccurately ‘translated’, can we build up pictures of them, but, spare as they are, Fowler’s details are telling, and the pictures are vivid. At first casually damning of Eleanor, out partying when the children arrive and finding that ‘it was too high up for her to go to the nursery afterwards to see her new little niece’, she hints at an emotional flaw for which the young woman, barely out of her teens, may not be wholly to blame: ‘She did not mean to be actually unkind, only she was utterly ignorant of how great a depth of sympathy and knowledge is needed by those who have the care of little children.’ Shadows are hinted at too, though not explored – this is a book for children – in Charley’s early years. His mother, Grannie Conway, ‘did not know much about children … or perhaps she had forgotten what she once knew. It was so long since the major [the children’s father] and his younger brother were little boys in the Cloverdale nursery, and that dear, dead daughter of hers a baby girl.’ What grief is hidden in those final words?

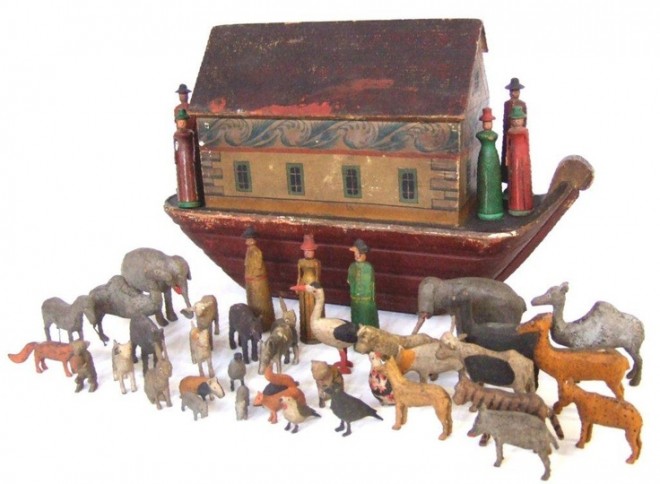

Little surprise that so much of the children’s ‘pretending’ centres on couples and families, entertainingly if a little worryingly somewhat dysfunctional: husbands turn into princes, or worse still tormentors, then, unpredictably, into lions; children disappear, lose their heads, choke to death at a ‘dinner party’. “Do people ever have the doctor right in the middle of the dinner party?” asks Babs. “They might, if they were very ill,” affirms her brother, with assumed confidence. What little the Conway children know of family life has been gleaned from Teddy’s reading; the world of the dining room like that of the drawing room is quite unknown to them. Life at the family home, has been lived between the nursery upstairs, with their beloved nurse and the kitchen downstairs, where cook was always ready with a slice of candied peel or some currants for a miniature tea party. The garden, the domain of their ‘best’, and only, friend, the gardener Giles has provided limitless space and scope for adventures. Babs and Teddy have been loved, and they have thrived at Cloverdale (what a comforting name) though Father-and-Mother have been distant creatures in a country they could barely name. The distance and their mother’s pain are brilliantly captured in one tiny scene. Aunt Eleanor has engaged a depressing governess, the very epitome of the wretched Victorian spinster, with no money, little education and no affinity with children or gift for teaching. Babs’ talent for ‘pretending’, does not extend to the casual pretence of everyday life, where truth gives way to politeness, and some thoughts are best concealed; the aptly named Miss Grimston writes to Mrs Conway in India complaining of her charge’s insubordination. “Beast,” she exclaims on receiving the letter. ‘Thereby echoing her little daughter’s sentiments of nearly a month ago.’ And a further month before any words of comfort would reach the nursery in Onslow Square.

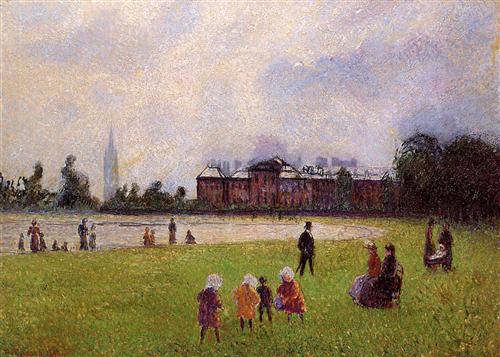

London, complains Babs, “isn’t nearly as big as the country … here you just see nothing but the streets, and there’s no far-away at all”. Birds in the park and the odd passing cat are poor substitutes for the chickens, and rabbits, kittens and dogs of ‘Cloverdale’; the nursery is ‘a stiff, straight room’ and Babs must exchange her grubby old pinafore, cotton socks and thick boots, for shiny London shoes, silk stockings, a clean white frock and, worst of all tight gloves, all of which are uncomfortable and none of which, to her aunt’s disappointment, make her look any more like the doll of her dreams.

Teddy in his charming new sailor suits is so much easier on the eye. ‘Wiser than some of their elders’, both children accept ‘the existing as the inevitable’, but the change in their lives is harder, more full of potential pitfalls, for Babs than it is for Teddy, ‘who did not care much really about anything’, and who as boy is and will always be on a looser rein than his sister. He will not want for Eleanors in his life.

The two children grow apart. Teddy goes to school, and learns to prefer organised games in Kensington Gardens, where they had lately sought scraps and stones among the leaves together but where he now ignores his little sister’s tentative waves. He is ‘quickly becoming the heartless, mindless, soulless creature which is generally to be found in preparatory and public schools’. Eleanor Conway recalls Charley as he was when she first knew him, ‘so superior to nerves in his rackety, fast steeple-chasing moods, which were Aunt Eleanor’s standard of manliness’ – a standard to which her little nephew seems likely to aspire.

While Teddy’s imagination fades, his sister’s grows luxuriantly, enriching her life immeasurably, but providing fertile soil for childish fears. Books which had provided so much material for their earlier games, begin to gather dust on his shelves: reading is ‘a fag’ for the schoolboy, while for Babs the world of literature is just opening up, ‘I like all stories what was ever written’, even sad stories’. Babs has had far more than we would consider now to be her fair share of sadness in her short life. The tender sensibilities that make her such a lovable character also make her vulnerable. Her future promises to be more colourful than Teddy’s but less certain. She will never have the same easy, but superficial, charm of her brother, but Fowler’s young readers (and older readers) are reassured that those who come to love her will do so unreservedly.

Babs will recover from the bruises dealt her during her stay in Onslow Square, borne with remarkable courage. What seems less likely is that Eleanor and Charley’s marriage will survive. Quite unwittingly Babs has chipped away at its shallow foundations, exposing Eleanor’s woeful lack of maternal feelings, while, ironically, awakening them in Charley. Fowler does not burden her young readers with lengthy confrontations between the couple, nor any in depth analysis of the flaws in the marriage. Some but not all would recognise the sadness of Charley’s sudden consciousness ‘of a great mistake somewhere, which could never be set right’. For the adult reader the whispered message is clear.

‘Make it a rule never to give a child a book you would not read yourself’, wise words from George Bernard Shaw. Like all the best books written for children The Young Pretenders, though we hear different things, speaks as clearly to us.