In the 1930s only 10% of married women had jobs. By 1957 (Daddy’s Gone A’Hunting was published in 1958), a third of married women had paid employment outside the home. But not the stockbroker-belt wives, not the married women of Penelope Mortimer’s fictional Ramsbridge, least of all those in its wealthy enclave, the Common, whose wealthy residents ‘need high powered cars to reach their otherwise inaccessible homes’ and ‘high-powered homes to make the journey worthwhile.’ The pursuit and the display of wealth is the binding force.

Daily, or more often weekly, for most have their pied-à-terre in London, the Daddies of the title leave their semi-rural high-powered homes for the city, to make the money to pay for their cars, their houses, their children and their wives, ‘stockbrokers and dentists, company directors and chartered- accountants, directors of advertising agencies and manufacturers of plastic’, followed by the literary agent, the film-maker and the playwright in a slower and less orderly peloton. Aside from the occasional shopping trip, spending such money as they are allowed, the women remain at home, running their houses, bringing up their families, playing bridge, meeting for coffee, or getting together after the children are in bed and finishing off their absent husbands’ whisky. They drink what their husbands leave in the bottle, and spend money that their husbands make. The only women on Ramsbridge Common who earn their own money are the daily helps and the foreign cooks, on whom those who can afford them are wretchedly dependent, German, Swiss or Norwegians, who are saving up to travel round the world, an adventure of which their employers can only dream. The wives of Ramsbridge’s commuting professionals are trapped in their gilded cages.

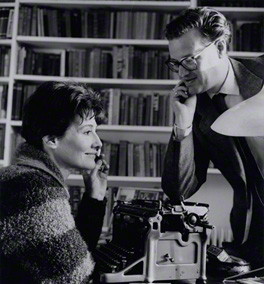

National Portrait Gallery

Penelope Mortimer was adamant that her writing was not autobiographical: ‘I never once wrote about myself, or the self who was doing the writing.’ ‘All my women protagonists were victims of their insensitive husbands; none of them did any work; they had children but didn’t get much pleasure out of them … God knows who they were, but I knew them well.’ Given John Mortimer’s behaviour, it is surprising that she distances herself quite so firmly from the women in her novels, but she did work, and very successfully (in 1958 she was the better known Mortimer), and she knew her characters very well. Sympathetically capturing both the superficial ease and the deep frustration of the Ramsbridge wives, she compares them to little icebergs: ‘each keeps a bright and shining face above water; below the surface, submerged in fathoms of leisure, each keeps her own isolated personality … a few have talent, as useless to them as a paralysed limb … Combined, their energy could start a revolution, power half of southern England. Drive an atomic plant. It is all directed towards the effortless task of living on the Common.’

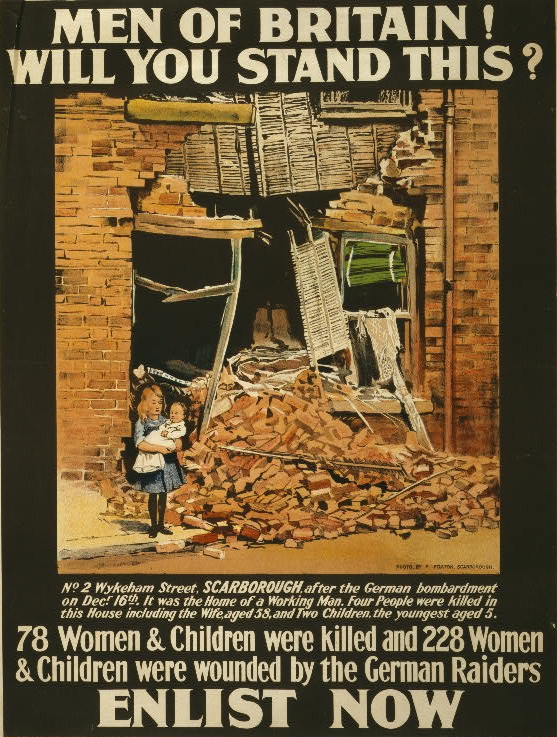

Nottingham Castle Museum and Art Gallery

Unhappier and more isolated than most is Ruth Whiting. She has few friends, her daughter has left home for Oxford, her sons are away at school, and after nineteen years she and her husband, Rex, barely tolerate each other. She is on the edge of a nervous breakdown. ‘Of course’, she says to an imaginary companion, ‘we had to get married’ – fateful words which mean so little to young women today – ‘I suppose we could have been happy in spite of that. But we never were. I think we hated each other.’ Abortion, illegal, not impossible but difficult, expensive or dangerous, had not been discussed (one of many things not discussed in this most non-communicative of families) . Eighteen-year-old Angela is the result of the unwanted pregnancy, and when she in her turn, and at the same age, finds herself in the same situation as her mother, the legal position has not altered – the Abortion Act would not be passed for another ten years – but ‘understanding’, risk-taking gynaecologists can be found by asking the right people, and at a price.

The time scale of the novel exactly follows Angela’s brief pregnancy, one school term plus one school holiday. Though morally confused (Penelope Mortimer herself wrote that she had an instinctive horror of abortion, although fervently supporting it in principle), Ruth is determined that her daughter’s fate should not mirror hers. She is no more able to discuss Angela’s abortion with Rex than she had been her own. Nineteen years on, denying his own history, Rex takes a dim view of teenage sex, ‘girls should stay virgins until they marry. It’s as simple as that.’ Furthermore he likes the militaristic, ambitious boyfriend. Tony is a man after his own heart. We are left wondering how the discussion between Rex and Tony might have gone, but it is not hard to imagine him insisting on marriage, and perpetuating the misery.

There is a dark irony in the fact that the out-of-work actress who (indirectly) supplies the name of a ‘helpful’ gynaecologist should be Rex’s mistress (suspected by the reader, but unknown to Ruth), and that the money to pay the doctor, for she has none of her own, should be the money Rex has given Ruth for a fortnight’s convalescence in Antibes, two weeks which he had planned to spend with the lovely Maxine, which he must furiously forego when she decides to stay at home. Ruth can’t tell him about Angela. Rex thinks she has found out about Maxine, which she hasn’t, angrily accuses her of pretending ignorance, which she isn’t, but fails to grasp either that she might be acting the frightened invalid, or that his daughter might be in any sort of trouble. Rex is even more unpleasantly self-centred than Ruth has hitherto realised, and Ruth is both cleverer and stronger than he has given her credit for.

‘Stop being so bloody innocent.’ Rex’s vicious outburst exposes his awfulness and marks a crescendo in one of a number of scenes in the novel written with the ear and timing of a dramatist. The chapter in which Angela tells her mother about her pregnancy is an almost pitch-perfect three-hander, with telling silences and utterly credible non-sequiturs. Ruth cannot reach out to comfort her daughter; Angela cannot see that her mother is in the middle of a breakdown. The ghastly nurse brought in by Rex to ‘care’ for his wife, interrupts with a string of bossy clichés. Rex bounds in and with affected bonhomie and almost comically total lack of empathy rounds off the scene, ‘Well, old thing, how nice to see you.’ The five-page chapter concludes ‘and kissed them both’, it is tempting to add ‘curtain’.

The comic and the absurd never fail to intrude on the serious. The all-important meeting between Ruth, Angela and Tony at the village tea room is interrupted first by an importunate dog, then by an inquisitive toddler. Hearing the unspoken, ‘I shall never do anything for anyone because I don’t believe anyone else except myself exists’, Ruth recognises Tony’s cruelty. Mortimer has already in just a few lines provided a damning picture of the vain, self-satisfied young man, with his ‘newly-combed centurion hair’, his shallow veneer of good manners, and assumed gravity: ‘He looked like a curate settling down to discuss dry-rot in the organ loft.’

Penelope Mortimer’s wit is never far away. The bumbling local doctor, called in to help Ruth in her breakdown, ‘had prescribed various brightly coloured pills, and after leafing through a handbook of psychology, suggested ordering a loom’; at ‘really tricky moments … he had brought in God as kind of senior consultant’. We can hear the professionally grave tones as clearly as nurse de Beer’s infantilising faux chirpiness: ‘We’ll tidy you in a jiffy’, ‘I told him you were just a wee bit weepy last night.’ Visual humour is just as sharp, brilliantly capturing some of the underlying strain of maintaining the appearance of ordered and opulent living, in the image of Ruth’s younger neighbour fiercely pushing a pram around the garden, ‘wheeling her baby smartly backwards and forwards over the lawn like an obedient, though curiously encumbered sentry’, or that of the local landowner’s Jaguar, speeding across the Common with a huge Christmas tree lashed to the boot, while ‘the pale set faces of the passengers, their dark clothes, made it look like a getaway.’ Two lines are enough to convey the vapidity of Rex’s mistress to be, ‘Maxine’s interruptions were like small landslides on a familiar path. The women stepped round them pretending they weren’t there …’ . Christmas on the Common finds the women running about ‘in a fluster, like nuns forced on a secular outing’, while the men ‘kicked the fires and opened the port and left parcels about for their wives to hide away.’ What a telling phrase. Apart from a plain spoken psychiatrist met at a Common Party, like most of the men ‘coarse in drink’, but ‘ordinarily helpful, ordinarily kind’, and the Austrian refugee Jewish gynaecologist, reduced to carrying out abortions in London and treated with contempt in the private nursing homes, an outsider, Mortimer’s men, the Daddies, don’t come out well in her novels.

Rex shamelessly declares, ‘I’m a natural bastard, that’s my trouble.’ Thinking that Ruth might have been unfaithful, he is almost relieved. The playing field might be levelled. ‘To be able to forgive for one act which he could understand, but of which she was unfortunately innocent could bring them both some peace.’ In reality Ruth’s misfortune is that she still finds Rex attractive. ‘She had learned never to trust him, but he could still tempt her; still by some rare gentleness betray her into hope.

Daddy’s Gone A-Hunting is full of quaintly period detail, tea rooms, and Vespas, knitting patterns and rock and roll parties for the middle-aged, non-working wives with foreign ‘help’, boys sent off by train to boarding school, and, less quaint, poor contraception and illegal abortion. It tacitly celebrates the changing moral climate which will allow Angela to return to Oxford, to make plans, live the dreams that her mother had to forego, while Ruth returns once more from putting her sons on the school train, gathers up her parcels, just as she did in the opening paragraph, puts on her hat and gloves, ‘her trivial armour’, and walks back into the gilded cage. At the core of the novel is the very contemporary theme of an unhappy marriage, bordering on the abusive, from which there is no escape.

‘It’s Angela who’s free.’