We have admired and loved so many home-front heroines in Persephone books, women who meet the challenge of war with fortitude and humour, un-conscripted women who find fulfilment in keeping the home-fires burning, digging for victory, making do and mending, and queuing, and managing unfamiliar, often extended households, in which their own children might be joined by those of others, relations or strangers, while husbands and fathers are absent, for months or years, or for ever. To Bed with Grand Music presents a very different woman in a rather different war.

In the wonderful Little Boy Lost (PB No. 28) published in 1949, three years after To Bed with Grand Music, Marghanita Laski would create the most convincing anti-hero in Hilary Wainwright. In To Bed with Grand Music she paints an equally convincing, anti-heroine, Deborah Robertson, bad wife, bad mother, whose war work, after a brief stint in a Ministry, is selling fake antiques to gullible customers in Mayfair. The novel was poorly received by (male) critics. Was it published too soon after the war? Were people too concerned with repairing damaged marriages and families, sweeping infidelities under the carpet in an attempt to move on, by putting the clock back? Or was there something unacceptable, unforgivable even, in a promiscuous woman, an atavistic horror of the sexually wayward wife, at a time when the very notion of Home (capital H) was sacrosanct?

In the opening scene, about to leave for the Middle East, Graham Robertson baldy tells his wife, ‘it’s no good saying I can do without a woman for three or four years.’ He expects no protest, and surprises himself with his own magnanimity when he promises, never to fall in love with anyone else, never to sleep with anybody who could possibly fill her place in any part of his life. At a time when women’s enjoyment of sex was barely discussed, would Deborah, or any wife, have dared to express her own equivalent need for a man? Laski does not state her position on the inequality, but we hear her the challenge.

From the start she invites us to question the marriage. When Graham says that he will be ‘thinking how bloody attractive you are’, Deborah immediately assumes that he is concerned that she might be unfaithful. There is an ‘ugly edge to her voice’ when she asks, ‘what about you?’ Is there a history there? The farewell is not the conventional tender wartime parting. It is almost all to do with sex, and not much with love.

Married just before the war, a week after her twenty-first birthday, when the novel opens she and Graham have a two-year old son. Timmy, we guess, was an unplanned baby: ‘… you’re glad we had him aren’t you?’, asks Graham, whose need for reassurance suggests that Deborah might not be the most doting of mothers. This is reinforced later by her housekeeper. ‘I don’t think Mrs Robertson is what I might call the mother type,’ she tells Deborah’s mother. Mrs Chalmer’s opinion is somewhat coloured by the fact that she wants full charge of Timmy, but Deborah’s mother concurs and does not discourage her daughter from seeking work, and more, in London, although she does not spell this out, even to herself. She recognises her daughter’s limitations as a mother. Mrs Betts is a perceptive woman but not a warm one. The relationship is not good, but she knows her daughter well, aware, for example, that her youthful wish to study at the Slade had little to do with a passion for art and everything to do with a passion for climbing the social ladder. The not unhappy widow of man who may have been more sexually demanding that she would have liked, she suspects too that her daughter may have inherited some of Mr Betts’s ‘tendencies’.

If Deborah reminds us a little of Lena Wiltshire in Saplings by Noël Streatfeild (PB No. 16), a passionate wife, but a reluctant mother, the two women differ in one very important way: ‘Lena never even pretended the children came first.’ Her husband Alex came first, and other than as attractive accessories she expected little from her children. In the Robertson household, and in her own estimation, Deborah comes first, and she demands a great deal of her son. Selfishly interrupting his games with other children so that he might rush to greet her, she basks in Timmy’s admiration, purrs when he offers her his favourite toys, is most pleased when the little boy woos her. Having made plans to leave for London in the coming new year (we guess it must be 1942) she puts no noticeable effort into etching his features on her memory, but brazenly poses for him in church at Christmas, so that he should remember ‘his mother’s lovely face in her little fur bonnet, the blue painted ceiling, the choristers’ voices, the deeply pervading sadness of Christmas in wartime.’

Rejecting the possibility of a job in Winchester, local and not uninteresting but with none of the potential excitement of London, she has had little difficulty in convincing herself that her reason for doing so is because she really wants ‘to stay at home with Timmy’.

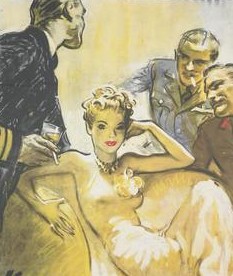

Betty and William Jacklin by Laura Knight

When London beckons, Deborah uses Timmy to justify behaviour which she knows to be wrong. Following her own selfish desires on the specious grounds that her absence will be good for him, she argues that she owes it to her child ‘to make him strong enough to face all the knocks of life rather than to protect him against them.’ Having lined up all her arguments she is able to escape from the increasingly tedious round of village life, convinced that she is showing strength and courage in leaving her little son, ‘a painful conclusion, but all sacrifice is painful or it wouldn’t be worth anything. The important thing is to see things straight and then face up to the sacrifices involved.’ For all her faults, Lena Wiltshire was honest about her relationship with her children. Like Hilary Wainwright, Deborah lies both about herself and, worse still, to herself. Later, but not much, an attractive GI has little difficulty in persuading her that she should sleep with him ‘for Timmy’s sake’.

It is not so much Deborah’s behaviour that Laski disapproves of as the bad faith. Long internal dialogues between Deborah and what she thinks of as her conscience, or even on occasion God, never fail to reach the conclusion that she wants. She is selfish and self-indulgent, with a professed belief in Providence which permits her to do exactly as wishes. ‘Opportunities made their moral demands’, whether it be the offer of a job or a flat, or the opportunity to be generously wined, dined and danced in glamourous surroundings, to be showered with expensive and hard to get luxuries. Opportunities that did not appeal could slide by unnoticed, it was immoral to disregard opportunities that did.’ Appealing opportunities abounded in the early forties.

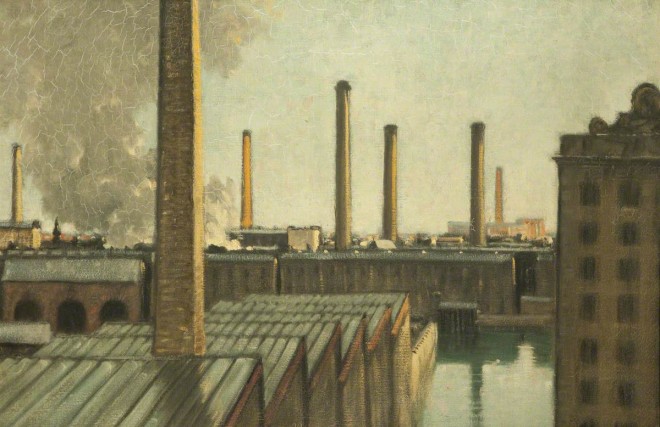

The war was bringing about change in many areas, not least in the position of women. Brought into the workforce in large numbers, many for the first time enjoyed an income of their own, however small. Forced to be independent, they began to enjoy their new status. Marriage was no longer the rock solid bastion it had been previously. In the year before the war fewer than 10,000 petitions for divorce were filed, less that half of those by husbands. By 1945, of 25, 000 petitions more than half were filed by husbands of which over 10,000 were on the grounds of adultery (from Millions Like Us by Virginia Nicholson). In her psychology evening class at Morley College in South London, Amber Blanco White, better known to Persephone readers, as Amber Reeves, daughter of Maud and author of A Lady and Her Husband (PB No. 116), keenly advocated sex before marriage – good for mental health – advised her students not to tell their husbands if they had a lover, and even went so far as to act out some more unorthodox positions in the interest of variety and fun.(Millions Like Us ).

There was nothing particularly unusual about Deborah’s wartime activities. What was sad about her encounters was that there was little love and less and less fun. Variety, however, was not lacking. American GIs, Frenchmen, Brazilians, Norwegians and plenty of English soldiers, and civil servants with wives safely tucked away in the home counties, no shortage of ‘opportunities’ for those eager to seize them.

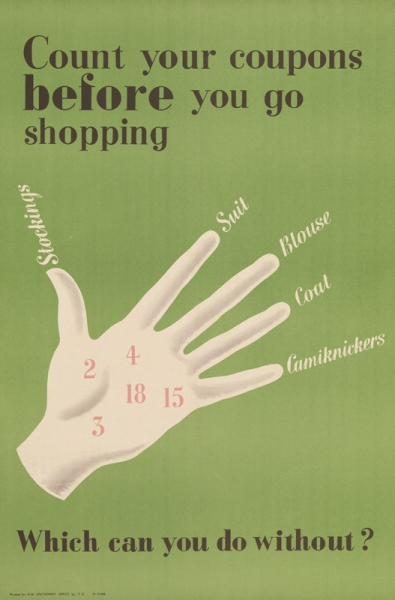

London was full of single men and women who had in Elizabeth Bowen’s words ‘come loose from their moorings’ (The Heat of the Day). The war had rewritten the rules of ‘social engagement’. Laski describes them with a cool almost anthropological eye. ‘Once the fundamental fact that all the relationships within the circle were extra-marital ones, the social life they entailed was as conventionally ordinary as the social life of ordinary married couples.’ Ordinary, maybe, but with added appurtenances ‘of almost as great importance as caste masks; it was essential that a woman should have a slim gold lighter and a jewel-encrusted gold powder-compact; that she should have smuggled perfumes and lipsticks and other fards from countries that did not take the conception of war as austerely as England.’ Laski does not pull her punches.

Believing herself to be starved of love, Deborah has slipped easily into the circle, drawn in as much by the glamour and the goods as by the sex. Two of her wiser and kinder lovers – for they are not all bad, and some are considerably nicer than her – caution her about the dangers. Joe, a gentle and generous American officer, warns her of a future passing from man to man. Pierre, a handsome and sophisticated Frenchman, who reluctantly and on her insistence, gives her lessons on being a ‘good mistress’, dares to suggest that once ‘qualified’ she may find it difficult to go back to being a good wife. Even her more sophisticated friend, Madeleine, her first guide on the slippery slope of infidelity, urges her to go home before it’s too late, ‘surely you want to go back and live with your husband when the war’s over and you’ve got a baby to keep you company while you wait for him.’ Deborah assumes that Madeleine is afraid of competition. She lies, why wouldn’t Madeleine?

Imperial War Museum

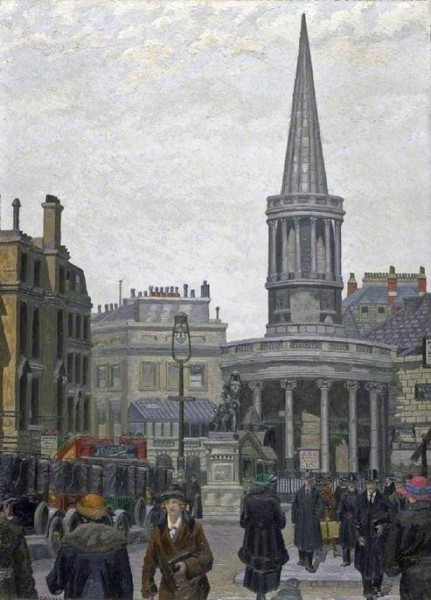

We are a long way from the drab England of shortages and rationing, grubby evacuees and lonely meals on trays, a long way too from husbands and children. In To Bed with Grand Music Laski shows us a different war, where women are not bonding in sewing parties or soup kitchens or factories or even over cups of tea. A lack of reliable female friends (the pretty ones prefer men, the plain ones are boring) is part of Deborah’s problem. Madeleine is good-hearted, but her marriage is history, she has more money than Deborah, and she makes no secret to anyone, and importantly not to herself, of how she has chosen to live. Deborah’s chats with other women take place mainly in the lady’s cloakrooms of glitzy nightclubs and focus on the lack of silk stockings and nail varnish, not the lack of eggs or oranges. Food at the Ritz, or the Savoy or the Berkeley Buttery was plentiful. The black-out and air-raids over London, which drained the energy of so many, can be turned to advantage. No gallant man would allow a woman to walk home through dark streets, and ‘Chivalry now demanded that a woman should not be left alone in a top floor flat [Deborah has, conveniently, found herself just such a flat] while the bombs flew past, so, as the alerts were more or less continuous, Deborah was seldom alone at night.’ Laski coolly, and damningly, adopts Deborah’s voice.

Deborah has had a ‘good war’. She is far from eager to pick up the pieces of her previous life; the roles of wife and mother do not appeal. Little wonder that ‘there was an air of disintegration’ in her life after VE day. There is no redemption. But Laski exacts no further retribution. One party is over, but she will find another.