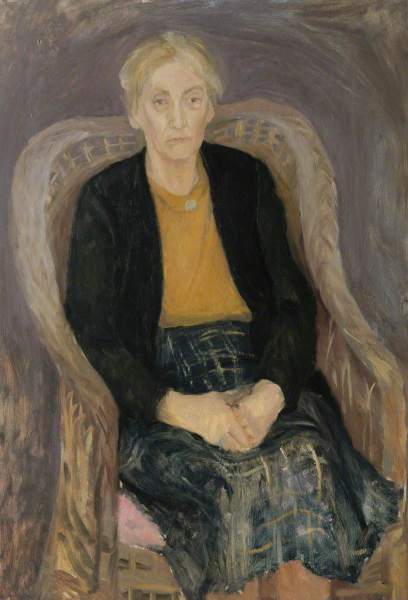

Louise Bickford is almost sixty, a widow, virtually penniless, and lacking any useful skills. Since her husband’s death she has taught herself to smoke, but is inexpert even at that. Nor can she recall having created anything in her life ‘except a hooked rug one winter when she was ill, and her three daughters.’ Looking back over the years she asks an old friend what she has done wrong. ‘You, my dear, have committed the crime of growing older. The greatest crime in our society. People shouldn’t do it. It doesn’t pay.’ In the 1950s sixty was not yet the new forty, or even the new fifty; for a woman alone, with no home and no money, it was most definitely the threshold of old age, an indeterminate period of dependence on reluctant relations, ‘Going from one to the other, trying to pass the time and keep out of the way in someone else’s house, temporising with visit after visit and no roots anywhere.’ Louise wonders what other women did in her situation, how they bore ‘this futile necessity to be housed somewhere, like a surplus piece of furniture.’

A rare cry of self-pity. She is, on the whole, brave about her situation, moving between daughters, Miriam, Eva and Anne, and a friend on the Isle of Wight, fitting her stays into their unwelcoming diaries, and adapting as best she can to their astonishingly varied lifestyles, trying with marked lack of success to make up for her inability to pay her way by ‘helping’. Only her youngest, Anne, ‘thick-bodied, ungraceful and slovenly’, accepts (gratitude would be too strong a word) her mother’s efforts to put some order into the damp, ugly stone house, the front windowless, ‘the back a jumble of windows that did not all open, with rickety coal sheds leaning against it among the battered dustbins, as if too exhausted to stand up under their own weight.’ Grey and faded laundry flaps over the untended garden, the ashtrays are full, the rugs crooked, and the geyser unreliable, but Louise feels more at home there in the flatlands of Bedfordshire, where Anne’s kindly husband, Frank, runs a tidy smallholding, than in Eva’s brightly painted London flat. Her sparky middle daughter is fond of Louise, but as a single, aspiring actress is, genuinely, for reasons of space and love affairs, the least able to accommodate her. She would prefer her mother not to do the housework but generally wakes too late to stop her.

Miriam is the hardest to please. Louise’s eldest daughter lives in Home Counties commuter belt with her lawyer husband, Arthur Chadwick, a rising junior counsel, possessed of a fiery temper, and a tendency to crane his neck stiffly, ‘in the habit acquired by a man who is slightly shorter than his wife’. Monica Dickens doesn’t pull her punches. Much to her father’s fury Anne married ‘beneath her’. Not so Miriam. The Chadwicks have a trimmed and tasteful house, surrounded by an orderly garden, where the daffodils are planted in rows. They have three children, employ a cook and a gardener and pretend, like all the other London escapees, that Monks Ditchling is a real village, though the pub is a cocktail bar and the grocer sells foie gras and peaches in brandy. Ouch! Miriam is ‘long, slender and fastidious’, she drives with her gloved hands precisely positioned at ‘ten to two’ and her underclothes drawer is ‘a joy to behold’. Unsurprisingly, her mother’s fumbling attempts to help only annoy. Even Arthur can see that she makes a poor job of the darning, and is not wrong when he (silently) rates her ‘deficient in nearly all the domestic qualities.

John Betjeman, Elizabeth Bowen and others praised Monica Dickens for her kindly humour, for her sense of comedy, for her affection for people, notwithstanding her debunking of suburban pretensions, and this is in many ways a comic novel. She is a practised people watcher and her observations and asides are brilliant, a mistress of showing rather than telling. Her dismay at the gentrification of villages having the misfortune to be on a good train line to the City is expressed in her description of the newcomers’ carelessly unkind takeover of Monks Ditchling’s ‘revels’: the dramatic society, run during the war by the WI, ‘who were now forced to retreat to the unassailable spheres of weaving and tomato bottling’; the fêtes, the pageants, the horse shows and Pony Club competitions, at which their precocious children dealt roughly with expensive ponies, while the village children stood by and jeered, where ‘occasionally a farmer’s son trotted hopefully into the ring on a fat, hairy pony with a rusty bit, and was mortified to find that his beloved steed hardly looked like a pony at all compared with the expensive well-bred animals that were cantering smoothly around, or giving a hysterical ride to some iron-fisted child whose parents thought that it must be able to ride if only they spent enough money.’

Born into comparative wealth, Monica Dickens was no stranger to life below stairs (as cook-general in a number of London houses), on the factory floor and on hospital wards (during the War), and was acquainted with the stratagems of thrift. Particularly important for Louise’s visits and stays in London was ‘the art of killing time cheaply’: half-price morning shows at West End cinemas, window-shopping, stopping wherever a crowd was gathered, dawdling in inexpensive tea shops, ‘holding a tray among a crowd of people with similar trays laden with unlikely food for the hour of day’. We have seen those people carrying plates of sausages and chips at three in the afternoon. This is not Lyon’s Corner House with its nippies, starched table clothes and afternoon pianist. The wind of the title blows Louise into Lyon’s Tea Shop the self-service poor relation. Enough said.

Monica Dickens never wastes a word and within the first three pages we have the back story, the skeleton of the plot and four major characters: Louise, ‘a small middle-aged lady with stubby features with hair no longer brown and not yet grey’, her late unlamented husband, her exacting eldest daughter, mother of school age children, and Gordon Disher, lower middle-class, thriller writer and bed salesman. The winds of Heaven blow and buffet but in biblical terms (and Dickens, like Louise Bickford was a Catholic), they can represent a point where the divine touches the natural world. Driven inside by the wind, Louise finds herself at a table opposite a soft-spoken, fat elderly man out of the ‘wrong’ social drawer who will transform her life, but not until the same winds have blown again, almost catastrophically, in the closing pages.

Fairy story, comedy of manners, family relationships, social commentary – class and money play a significant part – Winds of Heaven brings to mind so many Persephone novels: Miss Pettigrew Lives for a Day (PB 21), Miss Buncle’s Book (PB 81) , Princes in the Land (PB 63), Alas Poor Lady (PB 65), The Village (PB 52) and Louise Bickford belongs to the sisterhood of brave women, beating the odds with a combination of courage and the ability occasionally to seize their luck. But The Winds of Heaven is darker and quite remarkably contemporary. Louise can’t darn, she can barely knit, she can’t wash up without breaking cups, she has ‘never been able to make coffee’. Though frequently called upon for childcare she is not good with the little Chadwicks. A country girl by upbringing, when an emergency requires her to help on Frank’s smallholding, she sets to ‘with desperate incompetence’, convincing herself that she might accomplish ‘something useful for once in her life, but she can no longer remember how to milk a goat, the first rule of pig farrowing eludes her, with disastrous results, she struggles with the chicken feed and precious (still rationed) eggs slip through her fingers.

‘The chickens were grumbling at her as if she were an incompetent waitress who had got her orders mixed.’

Why, I found myself asking, is Louise so very incompetent, certain only of her own inadequacy? Why can she feel at ease only with her awkward grand-daughter Ellen? Why does she have so little self-esteem? Why do her daughters have so little esteem for her?

The clue is on the very first page. ‘… Her husband had set his heart on a son, and Louise was in the habit of giving him everything he asked for.’ For thirty-five years Louise had been in an abusive marriage. At the heart of the novel is an issue little discussed in the past, not named until 2007, not entered in the statute book until 2014, and not widely aired until last year when The Archers wove it dramatically into their storyline. The depiction of Dudley Bickford’s subtle cruelties is, as we now know, troublingly accurate, almost textbook: secrecy, particularly about money, aggressive silences, mockery, a slow chipping away at his loyal wife’s self-esteem. Monica Dickens may not have had a name for it but she knew it when she saw it. Some fifteen years after writing The Winds of Heaven she became a Samaritan. the most important thing she had ever done, she said. Her 1970 novel The Listeners was based on her experiences but there can surely be no doubt that she had been listening for years, and more attentively than the priest in whom Louise confides, and who suggests she pray for her husband to become mellower. When, of course, he doesn’t, yet again, and as he would wish, she blames herself. Young and in love, Louise had accepted Dudley’s refusal to marry in church, putting his pleasure above everything, only to suffer years of demeaning ridicule for her faith. Outright condemnation would have been too crude a weapon. Dudley orders meat for her on Fridays, makes jokes about priests, teaches his daughters to denigrate their mother’s beliefs; having isolated her from her church, he distances her from her parents, from her friends, and from her children.

‘… The girls grew away from her at a surprisingly young age. They had secrets, and private occupations, and found their own solutions to childish problems.’ The younger ones, in the by now, dysfunctional family, also grew away from the calculated tyranny of their father, Eva throwing her self into a rackety ‘theatrical’ life, Anne marrying the kindly lower-class Frank against his wishes (Frank’s parents had disapproved of him marrying outside his station). Only Miriam had been fond of her father, and she had been his favourite: ‘Like all bullies and boasters, he had despised those who believed his pretences, and he had favoured Miriam, because she saw through him.’ And Miriam shares some of her father’s characteristics. Her relationship with her mother is not entirely cruel, but it is controlling, and she would like it to be more so. Had she listened to her daughter Louise would have, reluctantly, spent the windy afternoon looking at paintings, instead of finding shelter, and more, in Lyons. She has views on her mother’s reading, on her wardrobe, on her London outings. She forbids her mother to look for a job: ‘Barristers who were rising to the top of their profession did not have mothers-in-law behind the haberdashery counter.’ Miriam has married a man not wholly unlike her father. Arthur, shorter in stature than her would have wished, is ambitious for himself and his two younger children, little Judy, with nasturtium-coloured hair and engaging ways, and Simon, his son who ‘was going to public school and Oxford’. Poor little Simon won’t have much say, nor can he escape his father’s mindlessly, and disastrously, cruel determination that he should shine at the Pony Club. Another dysfunctional family in the making?

Might the eldest, bonily plain Ellen with her rod-straight hair, and crooked teeth, an awkward cuckoo in her own family, but unconditionally loved by her grandmother, break free? Two fellow souls together? With a fair wind perhaps.