Holding the family blotter up to her mirror, among the patchy imprints of old letters and childish scribblings, Louisa Ashton makes out a recent address: ‘Miss Mabel Dawson, Springfield, Elton.’ That she should have been unaware of her son’s amorous ‘intentions’ neither shocks nor surprises her. Jim, in his thirties, has become ‘a mere lodger’. She is accustomed to the fact that he offers no information, and she asks no questions. But people, and events, leave traces.

Dorothy Whipple gently urges her reader to hold the mirror to the blotter. Having created fully rounded characters, she reveals them only gradually. They are true to life, precisely because we don’t know all there is to know about them. She never suspends the narrative to provide a back story but we don’t for a moment doubt that each character has one. Reading her novels (and her short stories) we learn to watch carefully for the most delicately dropped detail, and to listen for the slightest change of voice – her consummate mastery of indirect reported speech makes it easy to miss the moment when she exposes a character’s unspoken (never intended to be spoken) opinions, fears, regrets or desires.

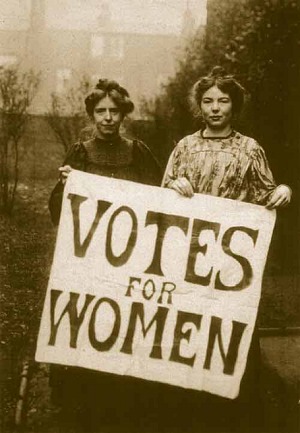

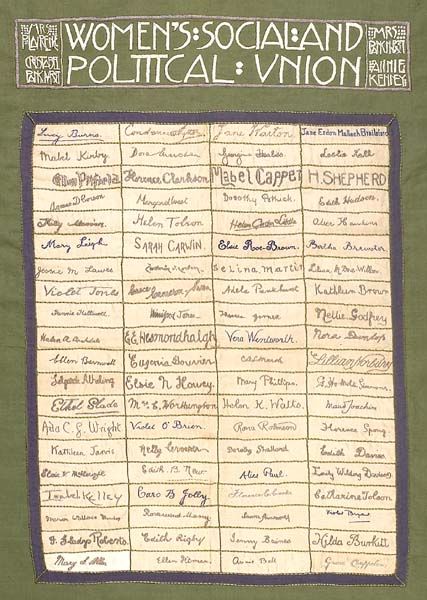

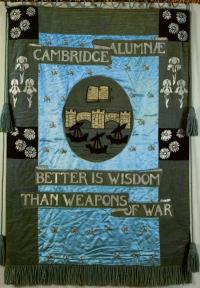

Greenbanks opens in 1909, eight years after the death of Queen Victoria and a few months before the coronation of George V. It concludes a few years after the end of the First World War, covering a period of social upheaval in the course of which women’s expectations were radically transformed, and the certainties of men challenged. Fifty-six in 1909, Louisa Ashton was born a Victorian, reared her children in a Victorian nursery, and, while far from blind to the unfairnesses of convention, is as reluctant openly to question the authority of her husband, her sons and even her sons-in-law, as she is to exchange her unfashionable bonnet for a twentieth-century hat.

Though not exceptionally so for the period, the Ashtons are a large family: Louisa, a diffident matriarch, her serially unfaithful husband, Robert, and their children, Thomas, Jim, Rose, Letty, Laura, Charles, and ‘the two other babies who had died’, quiet little tragedies not forgotten, mentioned but not dwelt on. Thomas, Rose and Letty have married and moved out of the family home, Thomas to Birmingham, Rose to the suburbs of London. Only Letty has remained close by, with her controlling husband Ambrose Harding and their four children, three sons and a daughter, Rachel. Three of the Ashton children are still at home: Jim in charge of the family timber business, Laura, and Charles, at twenty-six, the youngest son, adored, pampered and indulged by his mother, and an irritation to his siblings.

Like many large families the Ashtons find silence safer than speech. Louisa must cosset her favourite inconspicuously. When Ambrose (who values his own opinions too highly to keep them to himself) complains of his young brother-in-law’s idleness, she must stifle a caustic response, ‘her policy was not to say anything, to let remarks like that slide away without the emphasis of a quarrel, so that nobody would notice when Charles wasn’t really working at the timber yard.’ When Laura announces her (second), most unwelcome, engagement, her mother takes no risks: ‘Tell me about it, love,’ invited Louisa gently. She smoothed her face of all anxiety, in case anxiety should annoy Laura who was now so easily annoyed.’ Laura’s father’s attitude is not very different, though more cynically expressed. ‘I’ve never talked to any of them about these things. Not in my line at all … But don’t worry, Lou. Children will go their own ways. Parents are utterly useless after infancy. We feed and shelter them. That’s our part. What theirs is, I’ve never been able to find out.’

But while Robert finds distracting comfort in the arms of a barmaid, or two, Louisa does worry. She worries about those who, in the eyes of others, she loves too much, ‘Always there was this need of defending your children; no matter how old you got, you had to keep on with that …’ She worries about the child she no longer loves enough, Jim, fastidious and critical, and more difficult to keep house for than all the others put together, reminding herself how she prayed for his life when he had scarlet fever, how she fainted when his delirium ceased. ‘God had answered her prayers and saved his life, and now she felt awkward with him at meals.’ The table which in the opening pages of the novel was fully expanded to accommodate three generations of Ashtons celebrating Christmas, has, over subsequent Christmases, required the addition of fewer and fewer leaves. Mother and son sit across it alone: ‘… the cloth touched the floor all the way round.’ What an image of emptiness.

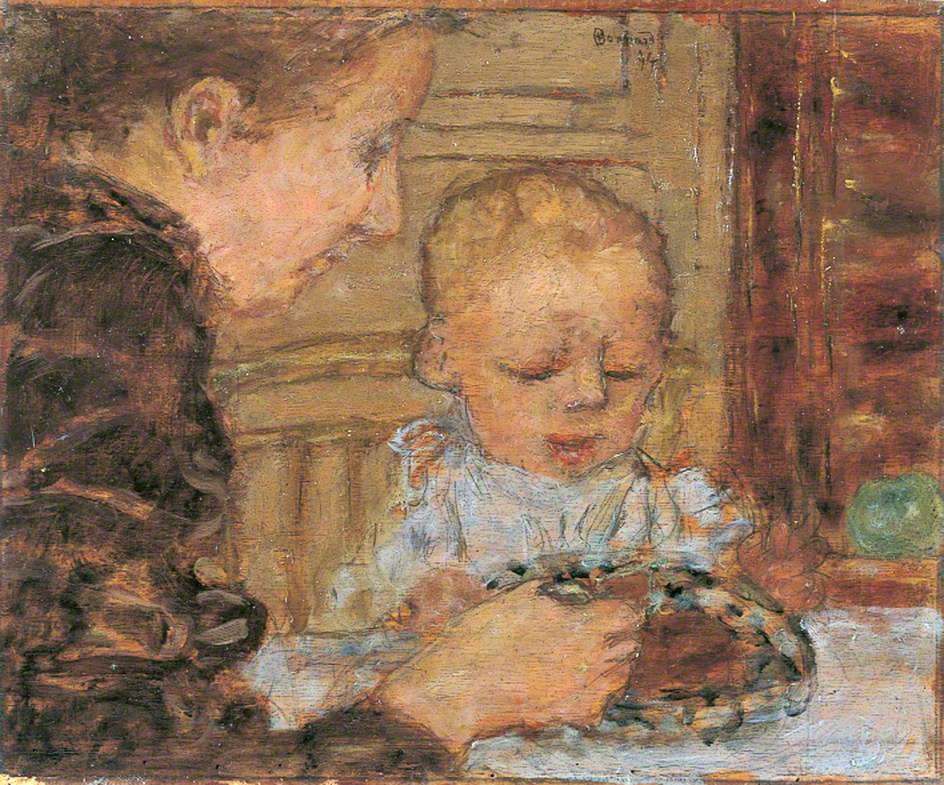

Dorothy Whipple skilfully holds the shot, letting the camera, as it were, do the speaking. The shrinking table tells the story of the shrinking family; Louisa’s chip bonnet affirms her preference for the past. A cigar speaks volumes about Ambrose Hastings’ obsessive unease concerning his status in the family, and the mild contempt which his wife’s father feels for him: ‘remembering anew, that, although good, it was not one of his father-in-law’s best.’ All those staccato commas, and the ‘anew’ – he’s grinding an old axe – brilliant. ‘Plum: October 10th 1914’: a jam label heralds the tragedies of the First World War. The variety of going away presents Charles receives when he leaves (at his brothers’ insistence) for South Africa perfectly illustrates his indecisive and dilettante character: a fountain pen, a revolver, a writing case, a ground sheet, a patent foot-rule, a shooting-stick, sleeve-links, a folding stool, binoculars, books and other implements of war and peace.’ An ottoman in Louisa’s bedroom holds a wealth of tiny memory triggers: the boned bodice of her wedding dress, the silk and lace ‘fretted in holes by the years’; a piece of sprigged muslin from the dress she was wearing as a young wife when she first saw Robert kissing another woman; a little night gown with featherstitching on the hem, in which ‘Jane, the tiny red-headed one, had died’. Traces. The exquisite detail of the featherstitching is as heart-breaking as the defining red hair. Whipple’s sensitivity to the delight and despair of parenting is remarkable. She and her husband apparently had no children, but one does wonder if in the first ten years of their marriage, before she started writing, there weren’t perhaps some little tragedies.

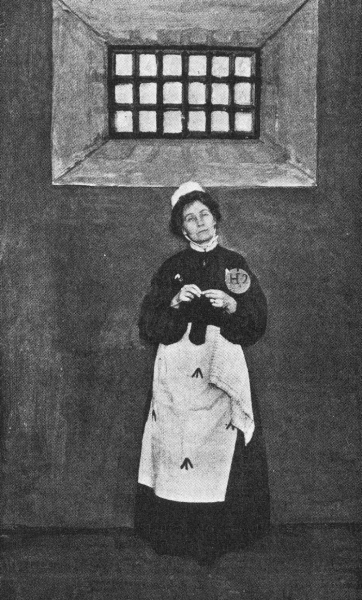

by George Phoenix. Wolverhampton Art Gallery

Dorothy Whipple asks us not only to look, but to listen, and not only to what people say. ‘Rachel’s feet made a light, quick patter, Louisa’s hardly any sound at all, because she wore flat shoes and did not nowadays lift them very high.’ We hear how, divided in age by more than half a century (which we already know and which Dorothy Whipple would not repeat) the old woman and the child keep step. The bond between Louisa and her youngest grandchild is central to the novel, the majority of whose characters are in their late thirties or early forties – what was then middle age, and they see life from very different angles: Rachel is too young, even in her teens, fully to understand the passions of the ‘grown-ups’, her grandmother too old. Louisa cannot comprehend the unrest of her daughters. Rachel, for whom her grandmother is somehow beyond age, thinks of her parents’ generation as old, too old for change, and, although she does not quite challenge their right to it, too old for love. Not assuming to understand each other, the two of them have a rich and fruitful relationship, which feeds both, and is, crucially, without expectations, or the consequent disappointments. Louisa can give as much as she feels able, and wishes to give, and asks nothing in return. ‘She wondered if she had taken the same deep pleasure in her own girls, and could not remember that she had.’ The comma most brilliantly captures a moment of reflection, and regret. Mozart is reported to have said that the most powerful effect in music was ‘no music’, the ‘perfectly placed rest’. Dorothy Whipple’s ‘rests’ are perfectly placed.

If Louisa and Letty were able to discuss it, which they aren’t – are any mothers and daughters? – they would find their experience of motherhood not so very different. Letty’s more hands-on approach has been no less dispiriting: ‘while the children were very young, it had been one long scramble to look after them; to get them up, put them to bed, feed them, see to their clothes, take them out, amuse them; and now that they were growing up they were growing away from her.’ Her husband’s lament is no less heartfelt, though more bitter than hers, less phlegmatic than Robert Ashton’s, and predictably to do with his own material sacrifice: ‘You denied yourself all the amenities of life; you lived in a small way in a small house, you had no car, you never travelled, you smoked inferior cigars, drank inferior wine, made your overcoat do three winters, did without what you wanted for years to pay for their education, and as soon as they were of an age to make some return, either in companionship or in money, they went off and left you …’

In addition, he finds that ‘Letty was no companion to him … It was as if she blamed him. Blamed him for what? Ambrose was bewildered and indignant.’ In terms of ‘return’, marriage is no less reliable in the long run than parenthood. Letty had liked Ambrose for being ‘solid’, unlike her father, and as the years went on found him (to her dismay) increasingly solid: ‘It was queer, it was frightening, she thought, how in life you got what you wanted.’ Her mother, Letty believes, lived for and through other people, but she ‘wanted something for herself’. Envious of her sister, Laura, who has made her bid for freedom and happiness, she pictures an ideal husband, no handsome Lothario, but one who would laugh at what she laughed at, enjoy ‘shop incidents, tram incidents, street incidents – all the queer, funny things that go to make up every day.’ Do we hear the author’s voice here?

In fact, Louisa’s resignation is not quite as complete as her daughter thinks. We have heard Louisa say ruefully (to herself), ‘it’s different for women; they bear what others do; they watch them come and go, they are torn and healed and torn again.’ Letty is brave, but so was her mother. Will Rachel come to recognise her mother’s enduring courage in staying in an unrewarding marriage, so poignantly described: ‘He gave her, more and more frequently, the same flat exhausted feeling she had when she tried to carry a mattress downstairs unaided … but of course you couldn’t give up; you couldn’t sit down in the middle of the stairs with a great burden like that; you had to carry it the whole way, until you could put it down somewhere final.’ Will Rachel later appreciate what it took for Letty to side with her against Ambrose, who disapproves of women’s education as fiercely as he disapproves of divorce and condemns illegitimacy.

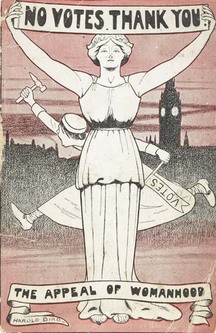

Ambrose later recognises that he has made mistakes, but we are left in no doubt that he will continue to make them. This staunch upholder of the double standard, who clings to the old order, as firmly as Louisa clung to her bonnet, feeling abandoned by his daughter and (more unreasonably) by his wife, plaintively asks himself what he has done not to be loved by them: a question which he lacks the self-awareness to answer. He will never embrace change, and history is not on the side of men like him. ‘The war had blown most people’s ideas sky-high, and the pieces had not yet come down. When they did come down, they would never fit together again as they had done before the war.’

The future belongs to Rachel, and to John, the illegitimate son of Louisa Ashton’s one time protegée and later companion, Kate Barlowe, for whom motherhood brought only social opprobrium. Forced to give up her son at birth, she has known nothing of the delights or sorrows of parenting, a sad story which subtly counterpoints the Ashtons’. Where they regretfully watch their children leave the nest, she is unable to welcome back the child who wants to rebuild a nest, with her. ‘The lust for saying “no” grew and flourished when she fed it daily’, and Kate, who has reached out once too often for happiness, is unable to embrace the redemption that John is offering.

At the end of They Knew Mr Knight (PB No. 19) Celia Blake thanks God for the fact things have, after all, been ‘put into their right proportion’. Louisa Ashton does the same. In spite of everything, they are content, comfortable, as the French expression goes, in their skin. ‘Another nice day,’ says Louisa’s maid, Bella, unblessed in looks, or love, but cheerful nonetheless. ‘For some, yes; for others no,’ adds Dorothy Whipple, from whom we do not expect conventionally ‘happy endings’. Her characters are so real that we can dare to speculate who might fall into the first group and who into the second. Laura, Letty and Louisa – yes; Jim, Kate and Ambrose – no. Will Rachel and John be happy? Possibly, if they seize their luck, and don’t expect too much.