Family, Humour, London, Love Story, Sex, Social Comedy, Woman and Home, and Adultery: on the Persephone website Patience features under an unusually large number of ‘categories’. Unexpectedly at the head of the list on the Patience page is ‘Men (books by)’. Excluding cookery books and Adam Fergusson’s The Sack of Bath, there are only ten others. Of those Patience is the most surprising, written, with remarkable sensitivity and understanding, almost entirely from the point of view of a young Catholic woman, about to be introduced, belatedly, to the joys of sex (or Sin as she has learned to call it).

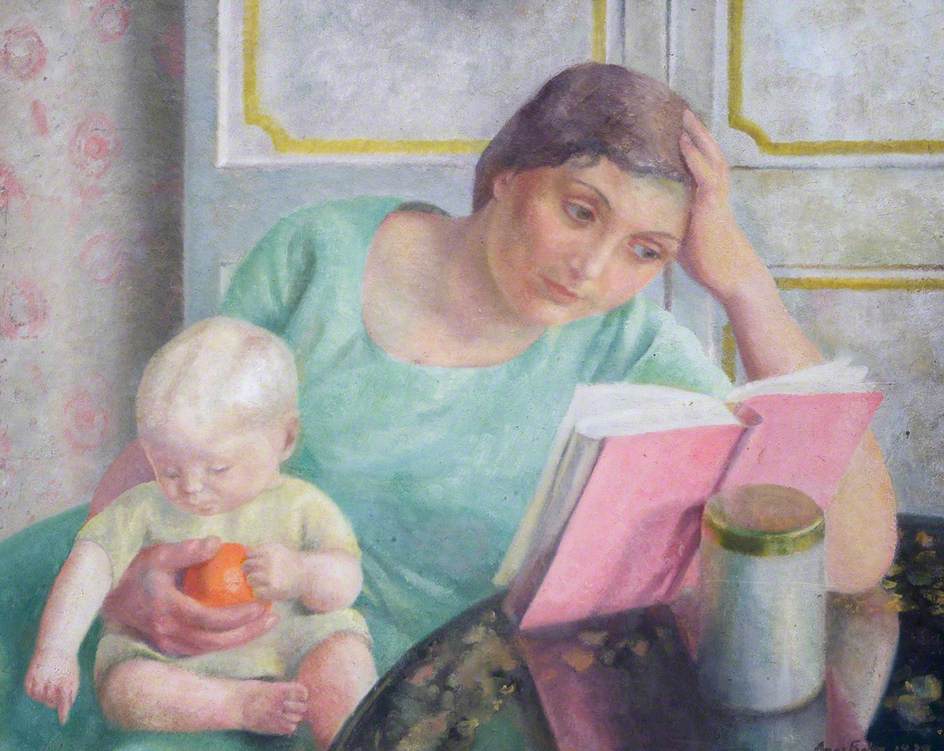

The Persephone Catalogue warns that ‘some will be shocked’, though adds that most will be ‘disarmed’. In television guidance- speak, Patience contains scenes of a sexual nature, as well as mildly irreverent language, which might offend some readers. But the sexual scenes are light-hearted, full of charm and humour, and the irreverence springs largely from the innocent, belated, questioning of a cradle Catholic. Patience is twenty-eight years old, married with three children and, it would be fair to say that her faith has not greatly matured since the cradle. Nor has her attitude to life and people in general. She is a trusting ingénue, who believes the best of (almost) everyone, and is happy to submit to the doctrine of church (in so far as she understands it), and to her husband. She sometimes thinks ‘it would be nice to be married to someone she could talk to’, but he is not actively unkind and she is not unhappy, except when one of the babies is ill. Her horizons are comfortably limited.

‘Patience loved her babies and Helen. She was sorry for Lionel. She was married to Edward. She was grateful to (and sometimes nervous of) Nanny and the Dane. And she liked the rest of the world. It was all quite simple …’ Helen is her younger sister, Lionel their older brother, and the Dane, her current maid – her sister has ‘an Austrian’. It’s the nineteen-fifties: a period of foreign maids, cocktails and clinic orange juice, residual rationing, nylon nightdresses, bed jackets, little girls in smocked dresses, and discreet sexual euphemisms. Men and women sleep together, after they have slept together; an attentive husband attends to his own needs, not to his wife’s pleasure, or lack of it. A very attentive husband is worse. Edward is very attentive.

Knowing that she might not have long to live, anxious to see her daughters safely married, her widowed mother had selected Edward for Patience, eighteen years older and previously married, but handsome, bluff and blond. For Helen she had found Charles, sweet and gentle, who ‘thought he was the marrying type for a month or two. Then decided he wasn’t.’ Helen, being the stronger sister, quickly found a replacement; Patience, true to her name, has made the very best of her lot. ‘But really the disadvantages [of being married to Edward] were negligible. The radiant golden beauty of the babies outweighed the rest of life.’ And indeed the nursery scenes are a delight, so tenderly observed: what mother has not tip-toed in on her sleeping children for one more glance? Coates describes the moment perfectly.

Neither of his brothers-in-law being Catholic – time was short, wartime casualties had limited the field, their mother hadn’t been able to tick every box – Lionel assumes the role of moral guardian to his younger siblings. He is obsessed with Sin, which to him means only one thing, as Patience knows: ‘Not unkindness. Not pride. Not gluttony. Not even cruelty to children. But Sex.’ Extra-marital Sex is a Sin. Marital sex (small ‘s’) is a woman’s duty. He has all but cut ties with Helen for leaving her ‘inattentive’ husband, and marrying ‘jolly, laughing, teasing’ Nicholas (most definitely of the marrying kind), to whom he insists on referring as her ‘paramour’, just in time for the birth of their equally delightful baby, whom he considers to be a ‘bastard’. As the novel opens he is about to break the news to Patience of her husband’s infidelity, news which meets with something less than the distressed reaction for which he had hoped. In an attempt to twist the knife a little further, he suggests that his young sister might perhaps have failed in her duty to submit to her husband (which is not true), or failed to remonstrate with him for his infidelities (which she has never suspected): ‘conniving at and condoning Sin by failing to correct it.’ We are left in no doubt as to the awfulness of Lionel.

Patience had been taught about the facts of life, delicately, by her mother, and instructed in conjugal duty by her priest. Pleasure had not been mentioned, nor has she expected it, deciding early on that the best way to take ‘lovemaking’ (no more accurate a term than ‘attentive’) was just to ignore it, passive resistance, to think placidly about something else, not, as her grandmother might have done, of England, but of the next day’s housekeeping. So when Lionel takes it upon himself to inform her that her husband’s attentions are being lavished on another woman, the latest of many, she is not so much shocked as astonished: she must love him very much ‘to do that if she isn’t married to him. And not taking any money either.’ She fleetingly conjures up an ideal scenario in which she herself would take the part of Mrs Edward Gathorne-Galley from breakfast till bedtime, and ‘the poor girl would take over till breakfast came round again’; the only downside to her plan being that, having slept undisturbed she would find herself approaching the Dane without a plan for any sort of meal in her head. She doesn’t share her fantasy with her interfering brother, to whom she most generously refers as Poor Lionel on the grounds that his wife, Peggy, has run away to a Retreat, where he can talk to her only through a grille, and is forced to pass important papers, requiring her signature, through the bars, rolled up into the size of a pencil. Lionel is a prurient religious zealot. In a different novel his role would be far more malign. As it is he is a figure of fun, who has failed to impose his will on his wife and whose rigid interpretation of dogma washes like water over both his sisters.

Patience is Edward’s second wife and he has enjoyed several mistresses. Far from ignorant that sexual pleasure is not a male preserve, in seven years he has made no attempt to help his child bride grow up. ‘He didn’t really say anything to her, not even Thank you. He just accepted what she had hardly known enough to offer.’ Coates’s voice seems to merge with Patience’s, as he angrily compares Edward’s acceptance of her submission to failing to teach a baby to open its eyes because one could see well enough oneself. And so for seven years Patience has been, like Louise Bickford in The Winds of Heaven (Persephone Book No.90) a good Catholic wife, submissive and dutiful. But Dudley Bickford was a cruel man (disappointed, like Edward, in his longing for a son – another story there) who had put his pleasure above everything, not only in bed, and subjected Louise to years of demeaning ridicule for her faith. Edward is more negligent than cruel. And Patience doesn’t have to wait as long as Louise for her luck to turn. Louise was already in her late fifties at the time of her life-changing meeting with Gordon Disher, Patience only in her late twenties when Helen introduces her to Philip, a divinely nice hero, with just enough baggage to be convincing, who understands women and is brilliant with children. Coates knows exactly what a girl needs!

If Lionel is a rotten brother, Helen is an excellent sister – Coates understands sisterhood as well as motherhood. When chance steps in and Patience is, after years with Mr Wrong, unexpectedly and thrillingly swept off her feet into the bed of Mr Utterly Right, it is Helen who gently explains, that ‘what had happened when she slept with Philip could very well have happened every time she had slept with Edward, in the ordinary circumstances of married life, which even Lionel couldn’t have described as Sinful.’ ‘Oh, but how unfair!’ cries Patience. ‘How did other women, the nice women she met in the park and talked to about clothes and babies, and who managed their husbands with such efficiency know these things?’ With Helen’s help, and a little casuistry of her own, she deals with the likely problem of spending eternity in Hell, which, since Helen would, obviously, be there too, and the babies might be granted visiting rights, mightn’t be too bad, and with the consequences of lapsing: ‘they quite like one just to go to Mass,’ her sister reassures her, ‘in the hope that it unlapses one, I suppose. And one can pray still. Not to God much, of course, but to someone not very important.’ Patience’s favourite intermediary is Saint Theresa of Lisieux, appropriately given her association with the image of childhood, and with flowers, both close to her heart.

Coates takes a wry view of the Catholic Church, but he doesn’t ridicule Patience’s faith, which he has her keep throughout the novel, albeit in a modified and rather personal form, accommodating the vexed question of Sin: ‘she had liked sleeping with Philip from the beginning, aware that it was Sin. And Helen liked sleeping with Nicholas in the same situation. And Peggy probably hadn’t liked sleeping with Lionel in a state that certainly wasn’t Sin, or she wouldn’t have run away.’

Lionel is a distinctly sinister character, who evidently harbours incestuous feelings for Patience, of which she is dimly aware. Edward is monstrously selfish, coming at one point close to committing marital rape but mercifully (and comically) stopped by the telephone ringing. However pressing the need to find husbands for her daughters, the girls’ mother could stand accused at the very least of wilful negligence in selecting a homosexual for the younger and more sensuous Helen, and for sweet, innocent, Patience a much older man with a somewhat dubious past, and old-fashioned views on wifely submission, conveniently chiming with the teaching of the Catholic church.

The social comedy has all the components of a social tragedy. Things might not have ended well, but this is a light-hearted novel, which treats serious issues with such a delicate touch, that on first reading one is barely aware of the darker notes. Helen recalls not the painful frustration of her first marriage but the expensive practicalities of ensuring that her infidelity is accurately recorded by the private detective (for which she has paid), never daring to take a taxi, ‘because it always meant paying for two, and he tipped so much.’ Patience does not agonise over her infidelity, but, seizing her luck and stilling her Catholic conscience, embraces Sin with enthusiasm, in such a hurry to lie down on Philip’s bed, ‘that she didn’t stop to take off her coat, which luckily was open, not being the kind that was often done up. But it didn’t matter in the end … because Philip took off not only her coat, but the rest of her clothes as well as his own.’

Coates writes sex brilliantly, managing to be both tender and funny, and for the period remarkably un-judgemental and egalitarian. Helen and Patience are strong women, and, as it turns out, so too are Poor Lionel’s wife, and Edward’s mistress, and his first wife. Sparkling with witty dialogue (Coates was a successful playwright), and moving seamlessly from one perfectly structured comic scene to the next, we realise as we close it, on reflection and with a little surprise, that Patience is also a feminist novel.