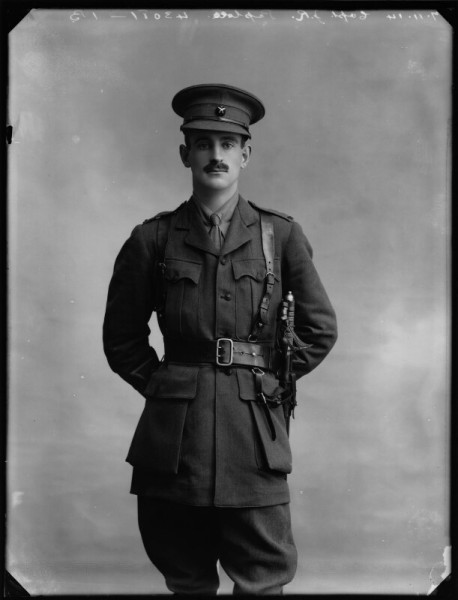

Only the large number of unmarried women and the small number of servants in Miss Buncle’s Book attested to the losses of the First World War, but its shadow hung, albeit faintly, over Miss Buncle Married. Arthur Abbott, Barbara Buncle’s publisher and husband to be, had, we learn (in a typical Stevenson aside) spent five years wearing a khaki tunic and a Sam Browne belt, waging war for his country. The uniform he found ‘becoming’ (personal vanity being one of his few faults), and the experience formative. Stevenson does not dwell on the carnage, nor the loss of his older brother. ‘If only he wouldn’t buck so much about his damned war (that old people are so proud of)’ complains his nephew Sam, who had been only four when his father was killed at the front.

All too soon Sam Abbott would have his own damned war. The seventh of an astonishing eight novels written by Dorothy Stevenson between 1939 and 1945, The Two Mrs Abbotts was published in 1943. The outcome of the Second World War was still uncertain.

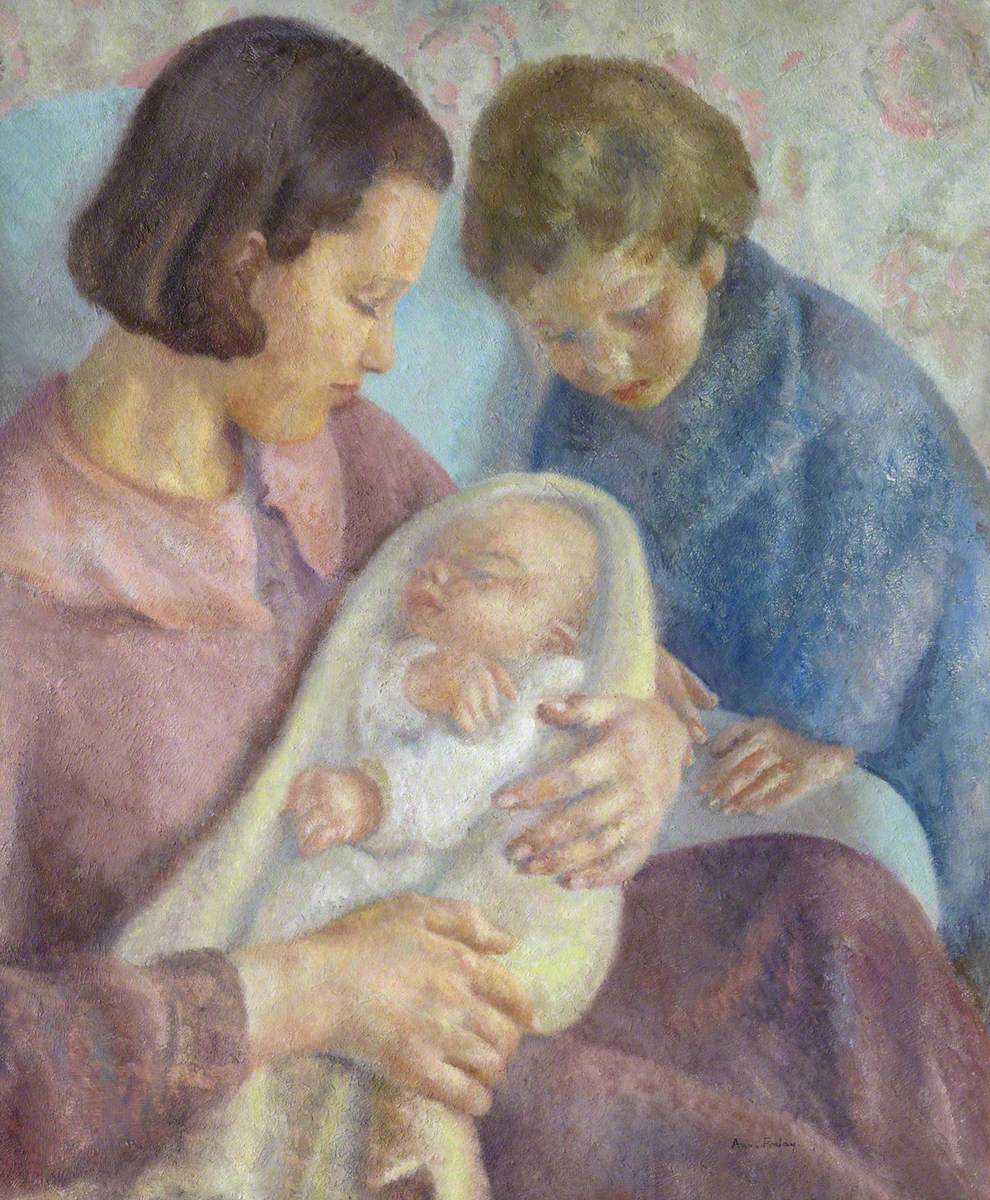

Seven years have passed since Barbara announced her first pregnancy to her delighted husband, Arthur, and put down her pen, to do something ‘much cleverer’. Barbara Abbott is now the mother of two: a son not unlike the Golden Boy of Miss Buncle’s Book in appearance, and an enchanting toddler who would seem to have inherited her mother’s disarming directness, a little girl of as yet few words, but clear views on the adult world. Wandlebury, the small commuter town to which Mr and Mrs Abbott moved after their marriage, is, like everywhere else in Britain, greatly changed. What had been a mostly settled population, familiar characters getting on with their lives in more or less predictable ways, has been shaken up and forced to adjust to a new reality. From meat to petrol, everything is in short supply, including people, especially people.

With a few exceptions, the young men and women are away in the forces or doing war work, returning to Wandlebury only occasionally, sick or injured, on leave or home for a rest. Some of the gaps have been filled by strangers, billeted soldiers on exercise, evacuee families, and various displaced individuals. Women are doing the jobs of men, the old are taking on the tasks of the young. Domestic work can fall to almost anybody, as can heroism. The world is a darker place but there are upsides. The humblest tasks are found to be a source of happiness, some of the unplanned encounters that come about as a result of the strange comings and goings of wartime prove very rewarding, and the most surprising people reveal hidden strengths.

Sam, having sown an abundance of wild oats, is fighting bravely, commanding tanks in the Western Desert. His wife, the ‘other’ Mrs Abbott, Jerry née Cobbe, Barbara’s dear young friend and niece by marriage, is doing her best at Ganthorne, their large house, with no electricity or adequate staff, and a regiment camped in the grounds. She misses Sam dreadfully, but, as we discovered in Miss Buncle Married, she is a coper, making do, mending and much, much more. Her livery stable is reduced to two horses. Of four grooms only one remains: Edgar has been killed on the retreat to Dunkirk, Fred is a prisoner-of-war in Germany, Joe a sailor ‘somewhere in the Mediterranean’, and the fourth, Rudge, is desperately trying to avoid active service on the grounds that he also grows the vegetables: ‘it ain’t my war … What’s Poland to me?’ he pleads, but Jerry is having none of it. She will not support his application. They will manage without him.

There must have been happy evacuee families, and happy hosts, but they rarely feature in wartime novels – not good copy. Jerry’s are more trouble than the horses and little better at keeping themselves clean. Mrs Boles is a sluttish, thieving mother, missing Stepney and her husband, with a large boisterous son, and a quiet pale but clever and, as it turns out, willing daughter, both predictably but hopelessly wanting what the Wandlebury children have: ‘… it was a vital problem and one that was being encountered all over the country … and [Jerry] could find no answer to it. She had never liked Mrs Boles but at this moment she almost liked her, for she understood, as she had never understood before, what Mrs Boles was suffering.’

Jerry’s grooms embody the fates of all the Edgars, Freds, Joes and Rudges in the country, and her evacuees typify the worst and best of the experience. A common dilemna tears at her brother’s conscience. Archie Chevis Cobbe has inherited the family estate. The one-time tearaway has transformed himself into a responsible and innovative landowner. Farming is a reserved occupation, he need not, some would say should not, enlist. But his contemporaries are being killed: can it be right for him to stay at home? Stevenson doesn’t labour the question, and, of course supplies a delightful solution. No spoiler!

The notion that her readers might measure their own difficulties against those of her characters is no more than hinted at. The deprivations and tragedies of the war are slipped into the narrative without comment. Barbara’s reflection at the butcher’s, where she haggles for a little liver to put with the few permitted ounces of steak, that ‘steak and liver pie for some reason sounded rather nasty’ is sufficient: food in wartime was sparse, unappetisng, hard to get and hard to cook. Arthur’s membership of the Home Guard is mentioned only en passant, as the reason for dinner being a less formal affair than before to enable him to get to the drill hall. The light fingered Mrs Boles would, we understand, be less of a problem were it not impossible to replace pots, pans, kettle and cutlery. Jerry sets off in a pony and trap – no petrol; a birthday present for Dorcas presents a problem – no fountain pens, cups, clocks, saucers, paper or string. Enough said. A brief and shocking history lesson takes up barely three lines: Lancreste Marvell’s friend and fellow airman ‘had flown over Germany fourteen times. He had been to Berlin and Wilhelmshaven. Hamburg, Cologne and several other centres of Axis industry had been the worse for Mr Ash’s attentions’. Not a word wasted. Just occasionally I found myself asking, is it Stevenson’s economical style, deliberate understatement or wartime spirit and decided it was all of those.

Jerry has her old governess loyally at her side. Miss Mark is one of several returning characters in The Two Miss Abbotts. Barbara’s old nanny Dorcas (subsequently housekeeper, and then personal maid) is in charge of the Abbott nursery. Some, like Mr and Mrs Marvell, the artist and his short-sighted, pathologically lazy wife, who played major roles in the previous novel, have only walk-on parts. Lancreste, their troublesome child, now a troublesome man, on (extended) sick leave from the Air Force, is for some of the time centre-stage. His unfortunate love affair with the gloriously dreadful Pearl stretches Barbara’s talent for sorting out relationships – match-breaking rather than match-making on this occasion. Markie is wonderfully fleshed out, given a rich back story, which astonishingly includes a university degree. A previously unsuspected interest in ethnology supplies a slightly far-fetched plot thread and places Sophonisba Mark (an equally unsuspected and surprising first name) firmly in the action.

The once downtrodden governess was, it turns out, one of the first women graduates of the University of St Andrews – her domineering father proving to have been more lenient than Dorothy’s, who forbade her to take up a place at Oxford (is this a late dig at her own father on the part of the writer?). With something of the New Woman about her, she had made a living, and a life for herself. Jerry has done the same with her livery business. Lancreste’s Pearl shares a flat and runs a stocking business with a friend. Nor must we forget that before she was married Miss Buncle made a living and more from her novels – Archway House is hers. There are some strong women both in Wandlebury, and passing through it.

Writing has been a means of escape from near penury to ease for Janetta Walters, another of Arthur’s authors., visiting to open the WLSP (Wandlebury Ladies’ Sewing Party – is it the pretentiousness of the acronym that makes us smile?) Bazaar. Her ‘high-powered tushery’ (Arthur’s words) have paid for her to move with her sister from a small stuffy house in Bayswater to a generous country house with a large garden and her own study. With titles like Her Prince at Last and Her Loving Heart Janetta’s books have sold in the hundreds of thousands, bringing in fan mail from all over the world, some, most usefully, attached to food parcels. The sudden onset of writer’s block threatens everything. ‘”I want to write a story about real people,”’ she says to her sister. ‘“It would be ruin!”’ Helen declared. “It would be the end of everything. Think of your reputation! Think of your public! Think of your sales!”’

In Miss Buncle Married, Barbara and her painter neighbour Mr Marvell discussed the creative process at length. She described writing as being more like hunting than building: ‘You start out to hunt a stag and you find the tracks of a tiger. It’s an adventure you see, that’s the beauty of it.’ Dorothy Stevenson was fascinated by it. ‘My own books,’ she wrote ‘are all novels, as it is the human element which interests me most in life; some of my books are light and amusing and others are serious studies of character, but they are human and carefully thought out …’. The Two Miss Abbotts is serious. The world is at war. But DES cannot help but amuse her readers.