On 15 February 1937, Eugenia Ginsburg was summoned to the NKVD (precursor of the KGB) office in Kazan. She asked how long the interview was likely to take. ‘Say forty minutes, perhaps an hour,’ was the reply. She would be gone for eighteen years.

By the time she was free again, Stalin was dead, along with her father, her mother and her elder son. Yezhov, the Commissar-in-Chief of State Security, had been executed, as had his replacement, Beria. Eugenia’s own personal interrogator, the smooth-talking Major Elshin, who had taunted her with offers of succulent ham and gruyère sandwiches, had died begging for bread in the very labour camp where she was serving out her sentence. World War II had come and gone, leaving twenty million dead, and the map of Eastern Europe had been redrawn. Five million had died in the gulag camps, one fifth of the 25 million who are reckoned to have passed through the system between 1929 and 1953.

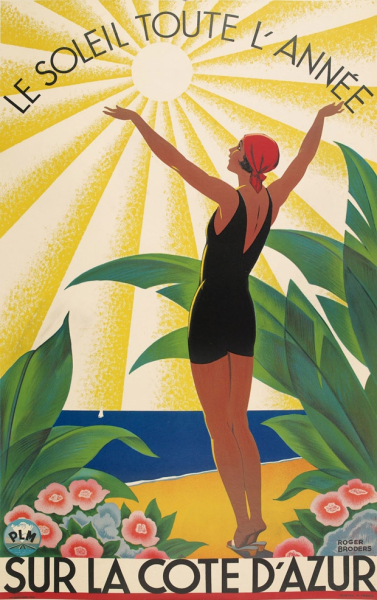

But the camps were not extermination camps – the deaths were a result of hunger and disease, maltreatment and exhaustion. They were labour camps. The endpapers of Into the Whirlwind are taken from a fabric celebrating ‘The Five Year Plan in Four Years’. If Stalin’s First Five Year Plan for the economy, launched in 1928, could be spun in this way as having largely met its targets, the Second threatened to be less successful. Many more factories and apartment blocks were needed, as well as roads, railways and canals; weapons would be required for the war that seemed inevitable. The workforce had to be expanded. Meanwhile, the prison population was growing: criminals were being joined by uncooperative peasants, workers, officials, academics, journalists, political dissidents – anyone (as Beria himself would eventually discover) could be arrested for political dissidence. The solution was simple: increase the number of labour camps, and put the prisoners to work.

Prisoners couldn’t expect wages, or decent food, or more than the most basic living quarters. The camps would be turned into a profitable sector of the Soviet economy. If more workers were required, finding new pretexts for arrests would present no problem. It would however be advisable to establish the worst of the camps far from any prying eyes: the Soviet Union had been threatened with a boycott of their wood exports, a major source of hard currency – their Western trading partners were uncomfortable with goods produced by slave labour.

Eugenia’s prison neighbour, Olga, correctly surmised what awaited them, ‘It must have become uneconomical to keep so many thousands – millions, for all we knew – without work. And think of the gigantic staff of the security apparatus – what that must cost! And most of the prisoners were of working age, between twenty-five and fifty. “They’ll not just deport us, they’ll send us to distant forced-labour camps”’. In the North-Eastern corner of Siberia, Kolyma, to which they were headed, was one of the worst and one of the most distant.

Getman spent 8 years in Kolyma, recording the horrors one year after his release in 1953. “I undertook the task because I was convinced that it was my duty to leave behind a testimony to the fate of the millions of prisoners who died.”

Olga Orlovskaya was a journalist, long divorced from her Trotskyist husband, but nevertheless arrested as his ‘associate’. Eugenia had been arrested on even more spurious grounds. Her husband was Chairman of the Kazan City Council. Both were avowed Communists, but a colleague of Eugenia’s had written an article found ‘to contain certain error in its treatment of permanent revolution.’ Professor Elvov was part of a Trotskyist plot, and she had failed to denounce him. There was no plot. The ‘proof’ that Elvov was a Trotskyist was that he had been arrested. Eugenia faced a second charge: she was implicated in the murder in Leningrad of Sergey Kirov, a prominent member of the Party, and one time protégé of Stalin. That she had never been to Leningrad was no defence: ‘He was killed by people who shared your ideas, so you share the moral and criminal responsibility.’ The system had its own tragically absurd logic, in which the crime was made to fit the punishment. Eugenia later shared a cell with a Tartar woman who had first been arrested as a Trotskyist, only to have her file returned when it was found that the quota for Trotskyists had been exceeded, ‘but they were short on nationalists’: Rimma was re-arrested as a bourgeois nationalist.

Rimma, adds Eugenia, almost as an afterthought and un-judgmentally, had denounced dozens of Tartar intellectuals and party activists, including her husband, to shorten her own sentence, which it hadn’t. Naming names was a ploy suggested more than once to Eugenia: as many as possible advises one friend, on the grounds that ‘they can’t arrest the whole party’, but, having decided that the only way was to be ruled simply by the voice of her conscience, she refuses to accuse anyone else, or to confess to trumped up charges. ‘I was left with the big advantage of a clear conscience and the knowledge that no-one else was pulled in through my fault or weakness.’

Eugenia doesn’t pretend to be a heroine, but she admits to being obstinate, and, above all, to being lucky, lucky in that her interrogation was completed before the introduction of ‘special methods’, torture in other words. She was lucky, too, in being in her early thirties, neither too young to grasp how to work the system, nor to old to withstand it, and lucky to have her own teeth and good eyesight – false teeth and glasses were not easily retained in prison. Others envy her higher education, but that, she writes, was of little use, compared with her physical endurance and, although she doesn’t dwell on it, her astonishing psychological endurance, as well as a belief that the absurdity would end. Having feared execution, Eugenia meets her first sentence, ten years’ maximum isolation in prison, not with horror, but as a challenge: ‘I made a resolution from now on to eat, sleep, and do exercises every morning. I intended to stay alive. Just to spite them.’

As it turned out, eating, sleeping and morning exercises would not be hers to schedule, but privileges to be granted or withdrawn, generally with no explanation. In the worst of the prisons the rules were particularly harsh, detailed, and arbitrary. It was forbidden, among other things, to go near the window, to sit with one’s back to the door, or to talk or sing in the cell. Penalties might include confinement in a punishment cell, or trial by court. ‘Yet,’ writes Eugenia, ‘all we prisoners wanted was that the rules should remain unchanged … that things should get no worse, for every day brought fresh signs of the growth of terror and lawlessness. Someone’s devilish ingenuity was ceaselessly at work, someone busily sought out each remaining chink in our tomb and plastered it over.’ She apologises at one point for her repeated us of the word ‘suddenly’, but justifies it. Changes were sudden, new rules were introduced, prisoners moved without warning.

Into the Whirlwind covers only the first three years which Eugenia spent in prison and in labour camps, three years in which she was moved four times, from a small cell in the NKVD headquarters, to a somewhat larger cell in the Kazan prison, larger but not large enough for the six women sharing its three bunks, then to the (still) infamous Butyrki in Moscow – thirty six to the cell, thirty six bunks with straw mattresses, but with one floor set aside for night-time interrogations so that sleep was disturbed by the screams of the tortured and the shouts and curses of the torturers. Butyrki was a transit prison, a brief stop on the way to Yaroslavl, where Eugenia was to begin her ten year’s solitary.

Eugenia describes one of her cell-mates: ‘With her long thin arms and large hands with bulging veins, Milda looked like the washerwoman from the picture by Archipov … She was accused of living it up in expensive restaurants … this was July 1937, when no-one cared any more whether charges bore the slightest semblance of probability.’

From the first days in the tiny shared cell in Kazan, Eugenia had understood the importance of communication. ‘To help break down the strict isolation from the world and from other prisoners … was one of the basic laws of prison life.’ She had learnt to value friendship, or, at the very least, companionship, to treasure the small shared victories scored against the guards, one of whose own basic laws was to maintain that strict isolation. From single words scratched in toothpowder on the washroom shelf, followed by a pattern of taps on the wall she quickly mastered the prison alphabet. Soon she was sharing not just information but poems with her ‘neighbour’, and successfully plotting for a badly beaten fellow prisoner to be provided with soap and cigarettes, tied together with threads drawn from her cell-mate’s dressing gown, a combination of resourceful improvisation, cunning and generosity that she would enjoy time and again. Political differences, and in those uncertain years, there were many, were, largely, forgotten. She invites our pity for the poor woman who in reply to Eugenia’s taps, asks ‘“what party do you belong to?”’ Making out the answer ‘“communist”’, she taps back ‘“I have no friend in that party”’, followed by a blow of the fist on the wall and a two-year silence.

With such rare exceptions the sisterhood holds together. From her account the men manage less well. Women sew on buttons and darn stockings for each other with needles stolen from guards, or fashioned from fish-bones. They contrive to keep their bras (not included in the detested prison uniform and therefore forbidden): washing them in the slop bucket, wearing them during the cell search (carried out by male guards), and hiding them under the mattress during the body search (carried out by female guards). They sacrifice precious sugar lumps for sick companions, make gifts of silk scarves, or scraps of warm clothing, and memorise the names and addresses of each others’ children and relations for “later”.

In her narrow ‘solitary’s’ cell, with its one iron bunk, iron table, iron chair and iron grille, the silence is more frightening than the rats, but she bears it stalwartly, until the day the system (suddenly once again) works in her favour. The overzealous programme of arrest and imprisonment having inevitably led to an insufficiency of single cells, Eugenia’s luck holds and she finds her sentence of solitary confinement commuted, by accident. For a year and a half she and her unexpected cell-mate are ‘united in pure sisterly neighbourly love’, a wonderfully rich period, described in fascinating and touching detail. When, suddenly as usual, the order comes for them to leave solitary for the labour camp, they wish that this break in their lives could be postponed, that they might have a few more days to wean themselves from their happy hermit life, reading, writing, and remembering their childhood. ‘Solitary confinement ennobled and purified human beings and brought to light their most genuine and deepest resources.’ Not the outcome that Yezhov, Beria, or Stalin himself had predicted or planned.

After a year and a half of something like calm reflection, the women must face the jungle law of camp life, which ‘was to degrade so many human souls’. Eugenia does not minimise the degradation, but applauds the resilience of human decency, reminding us of the value of random acts of kindness and convincing us that it might be possible to find joy in the midst of such appalling injustice and barbarity.

It is hard to tell to what extent her political conviction helped or hindered. Although some of her fellow prisoners kept faith with Stalin, Eugenia did not. But she didn’t question the Communist Party. Writing this memoir in the 1960s she asks herself if after everything that happened she would have voted for any régime other than the Soviet. ‘All I had – the thousands of books I had read, the memories of my youth, even the endurance that kept me going – I owed it to the revolution, which had become my world when I was still a child’, is her answer.

I have at the back of a drawer a crudely made badge bought in a Moscow market in 1989, in the heyday of Glasnost. It reads: “Everything is going to be alright”, or, more accurately “not bad” – Vsyo budyet neplokho. But today the Mayor of Kazan is in prison (the same prison as Eugenia), almost certainly on political grounds, plans to turn Butyrki into a museum have been shelved – it still houses 2000 prisoners, some political, still taking turns to sleep on the floor. What would Eugenia Ginzburg have made of that?