High Wages opens in 1912. The daughters of urban working class families could look forward only to domestic service or factory work, in Lancashire the cotton-mills. Those of impoverished middle class families might find a position looking after other people’s children, or their elderly relations, or, failing that, they might try to find employment in the expanding retail sector, which at that time provided board and lodging – an extra that was far from generous and rarely optional. Jane Carter, the seventeen-year-old orphan child of a journalist, with already two and half years’ experience, finds herself applying for a new position in a draper’s shop, the best in the Lancashire mill town of Tidsley.

On the day she delivered the manuscript to her publisher, Whipple wrote in her diary, ‘What possessed me to write about a girl in a shop? I know nothing about it.’ She may never have stood behind a counter, but the polished counters and shelves, and the multitude of glass drawers would have been familiar to any middle-class woman of her generation, and of mine. The last draper’s shop in our local town was still open in the 1970s for pins and needles and buttons, material and braids – beautifully described in Jane Brocket’s introduction. There were a few exceedingly dreary ready-mades in the window, but that was not their ‘forte’: one felt that their heart wasn’t in it.

The Miss Starlings were of the old school, like Mr Chadwick of Chadwick’s of Tidsley, where Jane is taken on at five shillings a week, plus (meagre) commission, and all-found: a none-too-clean shared room, where ‘the floor covering was a cold glassy oilcloth of a presumptive white’ and the merest of meals supplied by the penny-pinching Mrs Chadwick. ‘Shop assistants did not expect a great deal in nineteen-hundred-and-twelve,’ Whipple observes wryly. She shows such sympathy for the young working woman, speaks so convincingly in Jane’s voice and sees so clearly through her eyes, that it is hard to take seriously her claim to ‘know nothing’. At the very least she must have been an observant shopper, and appreciative of good service, to write so convincingly on the ‘art of retail’. I was reminded of Evangeline in The Homemaker (PB No. 7).

Jane, like Evangeline, proves to be a gifted and attentive saleswoman. Her feel for the stock, her eye for fashion and patient empathy with Chadwick’s customers far exceed those of Mr Chadwick himself, self-important, smug, set in his ways and socially insecure. ‘Slightly aggrieved’ on noticing that she spoke better than he did, he is pleased to make an impression on her, and having done so ‘looked for an opportunity to make another’. Making a display of his professional skills, running a length of sateen between finger and thumb, ‘he shot a glance to the side to see if Jane was watching his methods with intelligent interest. She was.’ In two words Whipple pricks the bubble of pomposity, and awards the first round to Jane. If there is a hint of sexual attraction in Mr Chadwick’s startled response to the movement of his new assistant’s eyelashes – ‘he hoped she wasn’t going to turn out to be one of those pretty girls. They were a nuisance. Flighty’ – it is brushed away. The Chadwicks are not likeable but neither are they sinister, rather figures of fun, to be mocked more than damned, and Whipple is brilliant at sticking in the pins (most appropriately in this case). Dressed for church (they chose St James’s ‘because it was good for business’) the couple do not cut quite the figures they intend, ‘Mr Chadwick in his morning-coat, his two scallops of hair showing like the wings of a bird that had got imprisoned under his bowler hat; Mrs Chadwick in a toque like a humble relation of Mrs Greenwood’s’, Mrs Greenwood being a much fawned-upon customer.

Dorothy Whipple selects a sharper nib for Mrs Chadwick than for her husband. In less than half a page she gives us a portrait equal to some of her best: ‘… a gold watch pinned by a lover’s knot over where her bosom should have been but was not … she sat in the upstairs sitting-room, her hands crossed on her hard front, looking out on the market-place and giving now and then a loud contemplative suck of the teeth. Mrs Chadwick was rather mean. Not excessively so; but just mean enough to add interest to her days.’ So concise, but sufficient to leave no doubt as to Beryl Chadwick’s petty unpleasantness. Dorothy Whipple trusts her reader to join the dots. There is an intimacy in her writing, so that one feels at times less a reader than a friend with whom she shares amusing details, almost whispering in our ear, confident that we will appreciate them as she does.

The humour is never laboured. Nor does she hector, but leaves us to deduce her message. In her Afterword to They Knew Mr Knight (PB No. 19) Terence Handley Macmath writes that ‘her characters seek happiness and wholeness in the same sense that the Greeks spoke of “salvation”… Her novels, although not overtly religious for the most part, are about wrongs being righted, people changing, sin being redeemed.’ Happiness is not the fulfilment of dreams, but rather the accommodation of dreams to reality. It comes at a price, most often, paradoxically as a result either of catastrophic financial loss or painful personal sacrifice. Terence Handley Macmath notes the grim wit and the biblical reference in the title of They Knew Mr Knight. High Wages resonates with similar irony and New Testament undertones: high wages can be the reward for hard work, but we must not forget St Paul’s warning to the Romans: ‘the wages of sin is death’.

High Wages, They Knew Mr Knight and The Priory all in their different ways deal with money and work and all are strongly feminist novels. Money is not of itself bad, but greed is. Money earned by hard work is good, money falsely obtained is evil, inherited wealth is debilitating. Major Marwood lacks energy and vision for the priory and the estate. Thomas Blake is caught in the slipstream of Mr Knight’s fraudulent dealings, Mr Briggs, husband of Jane’s customer, friend and later business backer, barely escapes being dragged down by his tax-cheating partner, Mr Greenwood. In all three novels working middle-class women (far from the norm in the 1920s and ’30s) stand as moral beacons in a world where men have failed. Carrie, the barmaid, makes a man of Thomas Blake’s ne’er-do-well brother, and generously helps out the rest of the family. Nurse Pye brings order to the priory; Miss Vanne, single mother and successful hairdresser, introduces the Major’s elder daughter to the world of work so that when the family is faced with poverty, she has the strength to learn dairying and cheese-making; the Major’s sister, Victoria the Artist, leaves the ease of the priory for a room above a pub and knuckles down to make a living from her dreadful paintings.

Work is redemptive, and transformative, but to attain to the ‘wholeness’ that Terence Handley Macmath writes about, requires tenacity. Sensing the ‘gratification of the business woman’ from the first, Jane is bitten, but it takes her seven years to progress from shop assistant to owning her own dress-shop, from tentatively advising on new trimmings and suggesting dress patterns, to signing the lease on her own premises and establishing her own contacts with London wholesalers, a world of men with wandering eyes and hands which she navigates with cool composure.

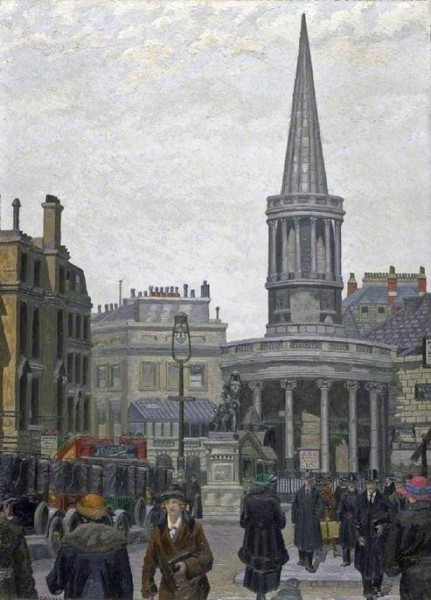

‘… she emerged into the top of Regent Street with a sense of escape. She looked at the little church with the candle-snuffer spire. She loved it.’

‘The Church of All Souls Langham Place’ by Charles Ginner. Fitzwilliam Museum.

Help in Jane’s venture has come not from her erstwhile employer, but from one his customers, and not his most esteemed customer, Mrs Greenwood, the ‘autocrat of Tidsley’, wife of the richest and, as we will later discover, most corrupt, mill owner. Jane’s backer is Mrs Briggs, a woman who has been raised, unhappily, out of her class – as is often the case with DW’s heroines – following her husband up a shaky social ladder into a house which is too big for her, and losing her role as housewife and mother on the way, as cooking and caring are taken over by servants. Mrs Briggs will find her own salvation in Tidsley’s new shop, which will bring not just a role, and a purpose, but, eventually, and unexpectedly, a handsome dividend. ‘I feel different,’ she tells Jane, ‘I feel I don’t mind so much what people think of me not being a lady and that.’ The previously dependent, shy and retiring wife will save the household from penury and imbue her broken husband with some of her own lately acquired strength.

Dorothy Whipple is particularly good at women, pleasant and unpleasant. Mrs Briggs is a sweet and generous woman. Mrs Greenwood the local grande dame, self-appointed protector of the town’s class structure, is forceful and bullying. The description of her is unsparing, ‘her maroon coat and skirt, her violets, her complexion, somewhat empurpled by the cold’ all matched. ‘“Rich and proud,” thought Jane, “and everything about her stiff and firm. Even the violets pinned tight. She wouldn’t let even a violet nod.’” This most esteemed customer is demanding and time-consuming and casually contemptuous. Whipple damns her equally casually, ‘Weeks later, Mrs Greenwood came into the shop to pay her bill.’ The italics are mine, the ‘dog whistle’ (to use today’s slang) is the author’s. To Mrs Greenwood’s dismay she has not been able to instill any of her (albeit unattractive and often ill-directed) energy into her daughter, a pampered girl, bored and talentless, with few friends and, in stark contrast with Jane, lazy and wholly lacking in staying power.

An article appeared in a 1937 issue of the Cornhill Magazine, quoted in the Dorothy Whipple entry in the ODNB, which captured the essence of her novels: it commented that in all of them ‘her characters struggle sturdily towards individual salvation’. The writer might have added that this only applied to some of her characters, those born with some aptitude for the struggle. Sylvia Greenwood is not one of them. Her looks and her mother’s tireless endeavours will secure an eligible husband, well-connected and with prospects (an earlier unsuitable suitor – a gloriously funny young curate, one of Whipple’s brilliant cameo parts – having been seen off) but not a fulfilling marriage, nor, it would seem, much fulfillment of any sort.

Even Lily, the Chadwicks’ lowly maid, and later Jane’s ‘live-in’ servant, with a drunken husband, makes good by dint of hard work, and a bit of luck: it’s wartime, Bob has enlisted, and while he drives lorries, she does well on her ‘separation allowance’. For some, indeed, the war had a silver lining. Mr Chadwick supplies linen to the VAD hospital, and ‘does well out of mourning’ though it falls to kindly Jane ‘to go to the afflicted homes, and fit the mourning clothes on indifferent bodies’ – how brilliant is that ‘indifferent’. Mrs Greenwood is in her element as Commandant of the VAD hospital, and even manages to bully an injured Belgian out of committing suicide – not all bad. Mrs Chadwick, by scrimping on the girls’ rations, ‘kept herself and Mr Chadwick plump and comfortable all through the war. She did her bit.’ Jane, feeling that she must ‘do something’ as the war ‘dragged on and on, all the exhilarating hatred and fine fury gone out of it; nothing now but a grim struggle between worn men’, makes tea for the returning soldiers, who include Noel Yarde, Sylvia’s husband to be, ‘one of those men, far more numerous than women can believe, who, if the flat truth must be told, enjoyed the War.’ We seem to hear Dorothy Whipple speaking very much from the heart here.

Jane’s admirer, an autodidact librarian, with a love of poetry and of the sound of his own voice declaiming it, returns from the war damaged physically and altered mentally. Wilfred, who had wanted so much to share literature and knowledge with Jane, had introduced her to H.G. Wells’ Ann Veronica (the novel of the New Woman, sexually liberated, based on his affair with Amber Reeves, author of A Lady and Her Husband PB No 116), and much else besides. By the time Jane is running her own business she not only has a grasp of French, she is familiar with the stories of Maupassant – quite an advance for a girl who left school at fourteen – which we must assume is thanks to Wilfred’s example and encouragement.

It is hard to avoid spoilers at this point. Suffice to say that although Jane’s sturdy struggle towards ‘individual salvation’ will succeed, it will be just that, individual. For a while, perhaps too long, she identifies with Ann Veronica, the New Woman. Her business career qualifies her as a New Woman; sexual freedom is an add on. But Jane is Dorothy Whipple’s creation and she must find happiness not in following her heart, because breaking up a marriage and leaving a child fatherless cannot be the road to salvation, but in becoming reconciled to a more modest and importantly moral path.