When Mollie Panter-Downes died in 1997 at the age of 90, the New York Times obituary writer concluded that, ‘For all her literary output, she was something close to a typical country housewife, one who did her own shopping, cooking and canning’. Canning? What do they know at the New York Times about the typical English housewife, which, incidentally, she most certainly was not? Mollie Panter-Downes contributed an astonishing 852 pieces to the New Yorker between 1938 and 1986, poetry, reviews, a regular ‘Letter from London’, and thirty-six short stories. The New Yorker described her as ‘bred in the bone English’, ‘every American’s English cousin’, but one wonders if a little of the exquisitely fine detail of her descriptions of English middle and upper-middle class life was not occasionally lost in translation. Bottling not canning was the English way, before, during and for some time after the Second World War. A detail, but Mollie Panter-Downes had 20/20 vision for detail, just as her ear was perfectly tuned to the voices and turns of phrase of her milieu.

To read Good Evening, Mrs Craven: The Wartime Stories of Mollie Panter-Downes is to look at domestic life in wartime England, or more precisely, wartime Home Counties, through a lens tightly focused, often, but not always, kindly, on the everyday. Beginning on 14th October 1939 and ending on 16thDecember 1944, the twenty-one stories, vignettes of the ordinary, containing no heroics, little drama and few deaths, reflect in their deliberately small way, the course of the war. The titles say it all: the first, ‘Date With Romance’, a doomed, but amusing, lunchtime meeting of old flames in the still unthreatening period of the Phoney War; the last, ‘The Waste of it All’, a marriage sadly tested far too early by wartime separation. Reading these stories sixty years on, we know about the course of the war. We know that the Phoney War would come to a brutal end in May 1940, and we know too that hostilities would drag on for months after December 1944, and that many marriages would be among the unlisted casualties.

There is a peculiar poignancy in reading these stories, knowing not only more than the characters, but more than the writer. To those concerned that their unwelcome guests, be they evacuees, or one-time friends, will be with them for the uncertain period of the Duration, we could offer some comfort: it will be over by 1945. We might warn those who know someone, who knows a man in the War Office who says the Germans are not going to send over many raids, not to be so sure. Mrs Peters tells Mrs Ramsay’s sewing party that, according to Mr Peters, ‘if the Americans came over and fought, we’d have the Nasties beaten before the end of the year’. We know from the date, 8th March 1941, that indeed it won’t be long before they come over, but it will be a long time before they get the Nasties beaten.

They cannot know what will happen in the future, and they have only the barest cognisance of what is happening beyond their own parish boundaries. Their war is on the home-front, and, if there is another front, it is a long way off, talked of on the wireless, and mentioned, but not dwelt on, in letters, which women read, or in newspapers which men read and keep to themselves. On the home front a few veterans of the First World War prepare eagerly to do their bit as air raid wardens, and some men, too old yet to be called up, have desk jobs in town, but most of the ‘Staff Officers’ now are women, and apart from a few over-age rheumatic gardeners, lame schoolmasters, or under-age paperboys, so are most of the Other Ranks. It is a woman’s world, in which even the food has been adapted to female tastes and appetites, served in portions small enough to sit on trays.

There are older widows in the big houses, young married women in pretty cottages, women who clean or cook for them, in humbler village dwellings, spinsters in small town flats or bedsitters. Mollie Panter-Downes looks with wry amusement at the power struggles fought across these domestic battle fields. The big class battle that will result in major social change rumbles far below the surface but there are small regular skirmishes.The calm of a sewing bee, briefly threatened by a trivial quarrel, is restored when conversation turns to hens and gooseberry jam. The tottering balance of a lunch party is saved by the timely sounding of an air raid siren.

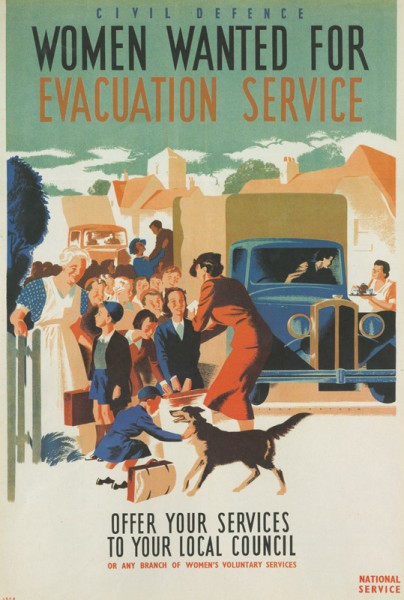

Far bigger struggles develop when the uninvited guests, or erstwhile friends, or, most problematic of all, evacuees, move in. This is enemy occupation in the home. Goodwill is tested to the limits. Tiresome Mrs Parmenter unhelpfully picks flowers, but never makes a bed, while her reluctant hostess pictures life twenty years on, her baby a grown woman, and Mrs Parmenter running out between the showers to pick roses for her wedding bouquet. Young Mrs Fletcher is disappointed by her evacuees: ‘it was natural they should look dingy, but she had imagined a medium dinginess that would wear off after one or two good scrubbings and a generous handout of gingham pinafores’. We hear her inner voice wishing that their needs ‘might all simplify down to something which could be settled by the stroke of a pen on a cheque’.

We can imagine ourselves in these situations, and know that our patience too would fail us, that our desire to do good would not be equal to the overwhelming desire to have our home back, tidy, clean and ours. We would do no better than Mrs Ramsay, or Mrs Fletcher, or even, perish the thought, than Mrs Parmenter. And so we can laugh at Mollie Panter-Downes’ descriptions. We are not mocking, it could be us. Nor can we cannot forget that the dreadful Mrs Parmenter, and the friends who have outstayed their welcome, and the evacuees, and Miss Mildred Ewing who drags her long-suffering maid from hotel to hotel, and thin Rachel Craig, with no hat and ‘a very good baby’, had homes once, where they would far rather be, but which may not be there when their exile ends.

Don Merrill is a painter, his wife an interior designer: now that London is filled with the fine brick dust of bombed out houses, they are redundant. What use is a decorator when there is nothing to decorate? ‘Even if people had the money to spare, they didn’t want to spend it on things which, experience had shown, were subject to splintering and mangling. The War Time Stories say little directly about the real and devastating splintering and mangling, taking place beyond the fiercely defended rural citadels. When the gunfire begins in earnest across the Channel, it is the shivering of the Palm Court windows, and the slopping of the China tea in the trembling saucer that make it real for Miss Ewing and the ladies in the San Remo hotel, Crumpington-on-Sea.

War makes people selfish. When food is short, you hide the chocolate. When fuel is short you hog the fire. Interrupted monologues replace conversation. People talk ‘only of themselves, their jobs, their bombs…’. Mrs Bristow’s concern is for her own children, ‘small and stranded and precious, in California’. How can she share her cook’s anxiety for her daughter in Singapore? When, like the Merrills, what you want is a party, the lack of available friends can make you angry and sad, and not always in equal measure. War generates a heartless practicality.

War can be absurd, and war can be fun. It can relieve the tedium of a humdrum life, it can give purpose to an aimless existence, solace and companionship to the lonely faced with the knotty problem of making sterile dressings in an unsterile drawing room, for as yet unwounded soldiers. The Pringle sisters are happy, ‘happier, as a matter of fact, than they had been for the last twenty-one years.’ Miss Birch will not find again the friendliness and warmth that she enjoyed with her neighbours during the terrible nights of the blitz. War can provide a square meal. The penniless painter, Don Merrill, enlists for the money. War is dangerously attractive. Reading of the death of his friend, Travers, Mark Goring is surprised to feel a pang of envy. The prospect of a posting to Delhi leaves him ‘hugging the thought that danger was as possible for him after all as it was for Nigel Travers or the next man’.

Mollie Panter-Downes paints sadness but she doesn’t paint tragedy – death and destruction happen at a distance. She picks out the courage, the stalwartness and the weaknesses of women, and a few men, with a fine brush and a light touch, preferring laughter to tears. Most of her characters are survivors, but they face an uncertain future. As the war and The War Time Stories draw towards a close, it is clear that her premonition voiced in 1940 was correct: things would never be the same again, ‘something of the Clarks [Mrs Fletcher’s troublesome evacuees] would be there forever’. The old retainers will die and no young retainers will take their place. Some like Janet Goring will fight against change, continuing to turn down the bed and lay out the pyjamas ‘as though another had done it’. When the elderly Mrs Walsingham welcomes a number of companionable, but not overly respectful, Canadian soldiers into her house, her loyal maid continues to believe that ‘things were just as they used to be, that their world which had come to an end could still be saved’. But trees must be chopped down to make space for military equipment , and ‘To tell the truth’ says Mrs Walsingham, ‘I think it’s an improvement – lets in more light and air’. Change is coming, and, like Mollie Panter-Downes she recognises that the bright side is the one to look at.

Questions

At The New Yorker, Mollie Panter-Downes was thought of ‘as bred in the bone English’. Do you feel that she tailored her stories to an American idea of Englishness?

Houses play a very important part in these stories. In what ways are they more than ‘bricks and mortar’?

Examples of Mollie Panter-Downes humour are too many to list and, like so much humour, hard to analyse. What makes so much of her writing comic? Is it ever cruel, and, if it is, does that make it less funny?

30 replies on “Persephone Book No 8: Good Evening, Mrs Craven: The Wartime Stories of Mollie Panter-Downes”

An excellent review which definitely whets my appetite for reading that book. Of course Mollie Painter-Downes adapted her style to conform with the New Yorker image of an English woman. (Not so much American, these considered themselves sophisticated and cosmopolitan. Accents tinged with Cockney have been admired as “typical” English accents in America, which may explain why Americans don’t on the whole do British accents very well. And vice versa – Brits I think don’t quite “get” that the American accent is regional rather than class.)

Thank you for the review and for your work publishing and perpetuating these authors!

‘Swept along’ is very apposite. I raced through the stories and loved every one of them.

I think they gave me a whole new perspective on the war and those who lived through it on the home front, a very human one which spoke to me as someone born well afterwards (well, a quarter of a century or so!).

So with that in mind, I do think the stories bear out Panter-Downes’ statement ‘I’m a reporter, I can’t invent’. Now I think I must go back and read them again…

These stories repay several re-readings. It is easy to miss small but telling details. As an example, one (of many) which I missed on first reading was in ‘Meeting at the Pringles’. After the meeting, which has achieved little more than a decision to start a subscription for lighting and heating (for their own benefit), all the ladies leave, happily convinced that they are doing their bit for the war effort. We get a momentary glimpse of the Pringle’s ‘little maid … struggling wildly among the folds of black rep with which she was completing the Laburnum Cottage blackout’. The little maid, is the only one doing anything truly useful and no-one notices.

Yes, I’m sure I will notice myriad new things on a second, more leisurely reading. That said, I’m currently re-reading ‘One Fine Day’ after a gap of around 24 years. The book made such a strong impression on me at the time and stuck in my memory but all the detail had disappeared. I wish I could remember specifically what struck me at the time but I’m sure it wasn’t the process of aging and becoming invisible that Panter-Downes describes so well, which is what speaks to me now at the age of 40!

It’s a long while since I read these and the review will make me re-visit as it reminded me just how much I enjoyed them first time around – each story like a little jewel. And totally the sort of book I am so pleased that Persephone has re-published.

I loved these stories. I went straight on to ‘Minnie’s Room’ too and then sat back all humphy and disgruntled that there were no more to read.

I find all the books Persephone publishes that were originally published during the war, very interesting. They have a ring of authenticity that modern books set during the war just cannot replicate. It is very strange thinking that the author had know way of knowing how the war would end either. I’ve gone Persephone mad and have to ration myself so there are some left. As I read them I divide them into my top-five, the first eschelon and the second rankers. So far I’ve only read one that I really didn’t care for (Fine weather for a wedding). Mollie Panter-Downes is in my top 5.

They whetted my appetite for short stories in general, though ‘Good evening Mrs Craven’ will always hold a special place.

I’m so glad to hear that Mollie Panter-Downes is in your top 5. The War theme continues in next month’s Forum, which will be about ‘Few Eggs and No Oranges’ by Vere Hodgson (Persephone Book No 9). The home front again but from a very different perspective.

Just had to pop in and tell you that I completely agree with everything you said. I was going to leave a separate post, but you voiced exactly what I was feeling! Two Jane/Jayne’s on the same wavelength!!!

i know a mrs. craven, so i decided to give this a try just on that basis and what a gem of a find! i loved it – a great insight into another time and place, and the language used just captures the mood so beautifully. i am now a fan of persephone as well as of mollie panter-downes.

kjc

One of the things I like most About Good Evening Mrs Craven and Minnie’s Room is that Mollie Panter-Downes writes about the banality of war. There are so many books written about the horror of war, from the Holocaust to the Resistance to the Blitz, in which terrible things happen and people can be heroes, but in a war like WW2, this is never going to be the full story. I feel that she captures brilliantly how, in many respects, the petty everyday issues and irritations don’t disappear, but get magnified, and when it comes down to it, few of us are indeed true heroes.

This is what makes the books human, and gives them resonance and relevance after 70 years.

I met Miss Pettigrew in the film and she led me on to Persephone Books and then to my favorite…Mrs. Craven and all the lovely English personalities that fill these stories. I laughed out loud (or should that be lol?) at the ladies debating the appropriateness of sewing for the Greeks. Then, the true hunger of Miss Bunker and the embarrasment Catherine Burch felt after her lovely time in the air raid shelter are so starkly yet kindly portrayed. Mrs. Craven is my bedside book: re-read countless times and just re-ordered for over a dozen times to spread the good news. She and her fellow characters have joined Miss Read in my love of all things English. Many thanks. Mary Ann Badar Swartz Creek, Michigan USA

I haven’t got the book in front of me, but it made a deep impression, most particularly the title story which I feel is a masterpiece.

Mollie’s articles for the ‘New York Times’ are propaganda; she is trying to arouse sympathy for Britain among the Americans, but her stories probe more deeply. The characters are not noble, cardboard figures who are interested only in winning the war. They do want it to be won, of course, but they also have urgent private concerns. They worry about absent men and children; they dislike letting strangers, and even friends, share their homes. On the positive side, one woman is delighted to be having her baby even though it couldn’t be a worse time – and, actually, her childless sister envies her. And meanwhile another young woman and her baby are turned away from a house which has plenty of space. And all over the country women sit down with a cup of tea and listen in fear to the six o’ clock news.

She is a shrewd psychologist. I liked ‘Goodbye, my love’, despite its title, because she gets the protagonist’s feelings so accurately; just as she has recovered from saying goodbye to her husband and is feeling fairly normal – he comes home and the emotional roller-coaster begins all over again. And the woman in ‘Good Evening, Mrs Craven’, who has been meeting the despicable Mr Craven once a week for dinner followed, presumably, by sex in her flat, for how many years? – his youngest child is eight. Even though the war has disrupted this cosy arrangement, and even though she thinks she can’t bear it, you just know she will hang on until he gets tired of her or until he is killed. Not all the men who fought were heroes. Not all the women behaved well either.

Her stories are so much more realistic and perceptive than the war stories I used to read in my brother’s comics.

‘At her flat standing in front of the mirror tying his tie …’ there is no doubt, I think, about ‘sex in the flat’, so delicately implied. You are right that Mollie Panter-Downes does not conceal the fact that not all the women behaved well, but she is not judgmental, except towards the monstrously self-centered Miss Ewing, and even she earns a little sympathy for her stalwart acceptance of life on the move, ‘with her maid, her jewel case, her travelling rugs – the sad little caravan which was all that remained of her treasure on earth’.

I enjoyed reading these stories, particularly the conciseness (concision?) of M P-D’s writing, from the mildly amusing descriptions, such as the flowers in ‘Mrs Ramsay’s War’, to the powerfully precise statements that sum up whole personalities, whole philosophies and histories.

I have recently acquired a Tudorbethan Triang doll’s house, made either just before the war started or from old stock just after it ended. So many of these stories (and those of Dorothy Whipple and other Persephone writers) could be taking place in such a house. I seem to be conflating the house and the books in my head now . . . .

And what a important part houses play in The Wartime Stories. Over half refer to a house in the opening paragraph. Mrs Ramsay lives in ‘a delightful little tudor gem’, Mrs Fletcher ‘at the manor’, Mrs Walsingham ‘in the big house by the river’ … Philip, in ‘The Waste of it All’, had wanted to leave his young bride in ‘their own home’, so that he might picture her there while he was away. She adapts herself to rural life, while he keeps it real for himself by sending instructions for the roof and plans for the garden. Separated from both, his house and his wife have become one.

Thank you all for your reminiscences of Girton but I hope you will forgive me for behaving like the bossy chairwoman of my reading group (see above), who brings us smartly back into line when we stray too far or for too long away from our book. Whatever the truth of the Girton girl’s image, I think we can all appreciate the pathos and humour of the picture, fleetingly reassuring to Mrs Bristowe, of a strapping girl swimming the last mile with a child under each arm.

How funny Marjorie, I too have a 1930’s Triang Stockbroker; it was bought second-hand about 45 years ago for my sister & has now passed to my daughter. I’d never thought of it as a potential setting for such stories. Perhaps I’ll see it in a new light now!

Having read the country cousin’s account of the book, I have gone back to it, realising just how much I had missed in one reading. It confirms my belief in the value of re-reading, of loved books of course, as well as those one had perhaps too easily dismissed.

Also excellent are MPD’s peacetime stories collected in ‘Minnie’s Room’ – especially the first three. I read them directly after reading Persephone’s Elizabeth Berridge collection, and she is good – but MPD is even better! I suppose she was interpreting the mad English to an American audience. Her style is beautiful and she has a sharp eye for the foibles of the upper middle classes, whose world is never going to be the same again after the war.

I’ve just re-read the stories and am so glad this forum inspired me to do this.

The point above that they were written in a context where the outcome was unknown is well made. Nothing written after can ever replicate that, even if the stories were written for a particular audience. Mrs Dudley may seem selfish – but she did not know that the war was close to its end – how many of us would put up with strangers in our home for an indefinite period with the outward politeness and calm that the women in these stories do? Miss Ewing’s behaviour, though self-centred, is also perhaps easier to understand if you put in mind that she had no idea that the war would end in 1945.

And Mark Goring – desperate to escape from the domestic round – would his wife have soldiered on with the chores and keeping up standards if she had known that the end of the war would not in fact bring an upsurge in domestic help but instead books like that wonderful Persephone reprint “How to Run Your Home without Help� (It does seem incredible to a modern reader that doing the washing up can be such a big deal).

One of the stories I liked best was “It’s the Reactionâ€. It just rang so true – both the loneliness of Miss Birch and the notion that, once a crisis event has brought us all together, that effect does not actually last and as time goes by we want to reclaim our personal space and drop the contacts the situation foisted on us.

I read “One Fine Day†four years ago and also cannot remember much about it, other than that I read it on a train journey and was utterly absorbed. Has anyone read any of the other novels and are they worth a read?

In one of the stories (I am afraid I forget which), the main character muses that even the sounds of her life are female, and that the very few men who appear (the very old & the very young) make sounds that jar – the loud, deep male voice is disturbing in her female-dominated world.

All the stories in this collection are of the female world of a nation at war. Men are in relation to women, and when they do exist, they are viewed – even by themselves – as acting a more female role. I suppose it highlights that war, especially then, is such a male sphere. The style of the stories, being female, is of a world that in many ways is not quite right, and known to be that way, but everyone just has to keep going.

Houses come into this because of the relationship – again, perhaps more stongly felt then – between women and houses. Women, especially the married women who are the majority in these stories, are the ones who make houses homes, whose work makes the bricks and mortor more than just that, and this is a time when houses are literarily blown to pieces. The war is destroying the traditional sphere of women in a particularly violent & sudden manner. And this is new for the second war – the first ww left the english domestic architecture mostly alone.

The destruction of physical houses reflects the destruction of society – the changes in class structure and behaviour that is touched on in many of the tales. Whether people like it or not, the days of staff/servants and the like is going to be as blown away as the houses that used to contain them.

I do think that the stories present a particular sort of englishness, and given her paying audience was American, undoubtedly it was aimed at that market. This is part of the work. But that perspective is always upper middle class, and even when servants, village women, or evacuees are allowed in, they are attribbuted beliefs that support the existing class structure, and provide a mild comic angle in their ignorance.

We are horrified by the uncleanliness (of different sorts) of the evacuees, but never really invited to see how difficult their position is, and how strange & scary the world they have been forced into is. We note that they are thin & dirty, but dont touch on what this must mean in terms of their usual living conditions. We are not shown that this elegant England with its nice old cottages (done up & gardened by poorer gentry, not still lived in by a labourer & family with no plumbing, electricity, food, and much vermin) & grander homes, not the one where men joined the army for food & money to keep their families (we have the artistic couple who do this, but it’s all rather amusing for them, not a matter of life).

This is the sort of England that makes far more pleasant reading & makes one wish to rescue it, rather than thinking the slums are probably better destroyed, and that a social revolution of a mild sort would probably help – why should these women who are not helpless or frail have others wait on them in such a way? Our families may have emigrated from the UK, but probably to get away from being servants & labourers, yet we fantasise about the gentry England, which is far more romantic, and much less smelly.

I do not say this is a bad or wrong attribute, but that it is a constant in the book, and must be acknowledged. I do enjoy many of the stories, some more than others, and find that I am pulling myself up from nodding agreement at how selfish these dirty evacuees have been, and how having to share one’s (large) house with a few other people whose husbands are sacrificing everything is not fair.

They are funny, and it is a quiet amusement, as though one ought not laugh out loud at the moment, but there is still a sense of laughing at the working classes in a way we dont laugh at the narrating women. We do laugh at the men a bit more, but they are wrong in the world of the stories.

Am trying to get hold of more of her stories to read, and do re-read them with pleasure.

A reader in 2011 is training a telescope onto the England that Mollie Panter-Dowens examined with a magnifying glass. Her magnifying glass was of its time and she chose to focus in tightly on the world and people that she knew and understood best, the middle and upper middle classes. But when, from time to time she holds her glass over those who do not belong in that comfortable milieu, her eye for detail proves just as sharp. Under the eye of Captain and Mrs Fletcher, the father of the evacuees wheels his baby in a push-chair. ‘Mr Clark’s cough floated back to them, resigned and dispirited, like the droop of the shoulders under his shabby coat’. MPD’s sympathies are far from one-sided.

The destruction of houses indeed reflects the collapse of a certain social order, and, by the same token, the desire to preserve them stands for the desire to maintain that social order. But houses are also, and very importantly, the embodiment of personal space, physical and psychological, a space which is being threatened on several fronts, and which is jealously guarded, and missed. The ‘silent Sparks’ loathes the nomadic lifestyle that Miss Ewing imposes on her. Mrs Fletcher’s evacuees, like Mrs Dudley’s, are as anxious to return to their homes, as their hostesses, for want of a better word, are to see them go. While it is true that neither Mrs F nor Mrs D seem capable of understanding this, which may be viewed as a bad mark, they are acutely aware that, while their physical space can be scrubbed clean, the brush does not exist that can restore that other less definable space to what it was. Mollie Panter-Downes is quite clear that this is a good thing.

In my original response, I found that I wanted to highlight the points & themes that I found raised themselves when I re read these stories for about the 5th time.

If a book is to continue to be read & valued, it needs to be responded to from a current perspective, not merely made allowance for bc of when it was written. We often do that regarding race, anti-semitism, and sexism, accepting that at the time, such views were held, even though we now do not do so. Class & social representation of it was, at this time, already a major public issue, to ignore it would be to detract from the insight that the stories provide. It was part of the world that produced the work.

I did note that I thought there was nothing wrong with her concentrating on the society she knew, but as a reader, each time I read (& enjoy – the only reason they’re not on my bedside pile of Persephones is I got the colour cover not the grey one & Im obsessive) the stories, I find I am more strongly seeing what there isnt.

The author does see the few workers/servants/so on & present them with sympathy, but we are not invited into them in the same way. Perhaps that is a deliberate part of the work, or perhaps not. Perhaps she felt stories from the perspective of people moved out of their slums wouldn’t sell as well – few of us want our day dreams of what life is like in other countries spoilt by too much realism, even during war. Or she just couldn’t do them as well.

Houses in books by & about women are always of multiple meanings – sometimes more obviously than others (Elizabeth Goudge’s Eliot saga for example, let alone about a zillion others from everywhere). They are, of course, personal & reflective of the body, and the use of smell, especially can make one aware of how very personal they are & how invasive others – and their smells – can truly be. I just felt more like blowing things up when I was writing. Perhaps a reflection of having also been reading about the attacks on property by the suffragettes – showing, maybe, their understanding of the effect of attack a politician’s home?

I do love this format, but trying to write down all that one thinks of as a reader would result in far too much for anyone to read…discussions are great.

Re the comments about lack of stories re workers and similar, I imagine that like many writers she stuck to the rule of writing about what you know. Her observations on servants or working class families reflect just that. She perhaps did not feel she had the insight or confidence to put herself in their place and write from their perspective. Maybe an ability to write about what one does not know is a distinguishing feature of a writer who is great as opposed to merely good or popular or enjoyable.

Do look at The Persephone Post for 24th February. You will find an interesting reply to your comment and a wonderful painting by Vanessa Bell, ‘The Cook’.

What distinguishes a “great” writer from a “good” writer is the breadth of knowledge or depth of knowledge but never the ability to write without knowledge. For that we have all too many examples.

Comment on Mollie Panter-Downes.

I, like Miss Heliotrope, have tried to beat down a sense of unease reading Mollie Panter-Downes. I suspect her heart was in the ‘right’ place just as Winifred Peck’s was – feeling somewhat guilty about her privilege and cheerfully accepting social change – but I just cannot get my head around the trouble these ladies seem to have had when compelled to do their own housework. My two grandmothers reared families in urban/village Ireland (one with 5 children, one with 9) in the 1920s, 30s and 40s with no household help whatsoever, one of them in a house with no piped water – and all their children got apprenticeships/public service white-collar jobs or third-level educations. (Some emigrated but not until they were well-reared). They loved reading and going to the pictures and gardening and music, and were in every other way quite similar to the Panter-Downes/Peck ‘ladies’ except for this fact. Surely there must have been women like my grandmothers in Britain too?

CC

I know what you mean but it has to be read in its social context ie the standards and aspirations middle class English families had re their lifestyle. If nothing else, having servants meant you were at a certain level socially.

Thus the expectation pre 1939 in middle class England was that you had servants and even in less well off households you would have had or tried to have someone to do the heavy work ie the dirtier and nastier bits. You would have had a large and time consuming house which in itself dictated needing help.

The standards you were meant to aspire to in keeping your house clean and well run are reflected in Kay Smallshaw’s book “How to Run Your Home without Help”.That book made me understand why my mother spent so much time on housework!

Of course thousands if not millions of women did not live that way. They would have considered having a bathroom the height of luxury. The stories show in a small way the clash of 2 worlds brought about by evacuation – people meeting whose lives had not really crossed before. Pre war many families in England still lived in one room. (I’m just reading or rather dipping into a large volume of Thirties history and the chapters on living conditions are truly shocking) If you are in the UK and watching the adaptation of “South Riding” the shacks are a prime example of that.

Middle class women were very preoccupied by the servant question – it comes up time and again in both 1930s literature and social history. My own late mother in law was still of that ilk and felt it was very important to have “help in the home” – an idea which would have been alien to my own mother – reflecting their very different social backgrounds.

One of the reasons I enjoy so many of the Persephone reprints is because of the light they cast on social history.

Mollie Panter-Downes is indeed writing about a particular group of people at a particular time. Quentin Bell in his biography of Virginia Woolf has a very interesting chapter on servants (I cannot quote because I gave away my copy to a Russian friend in 1990). It only takes a power cut to remind us how reliant we have become on our washing machines, dishwashers, freezers, vacuum cleaners, central heating, electric mowers … and, of course, on those who maintain them for us. I am not equating people with machines, merely suggesting that we show a little sympathy for the women trying to run their houses, as well as for those helping them.

The story, ‘It’s The Reaction’ by Mollie Panter-Downes was recently read aloud on BBC Radio 4 Extra.

It’s still available on BBC iPlayer – http://tinyurl.com/3ty8km3 – very skillfully read by Sylvestra Le Touzel.

Very much well worth a listen!