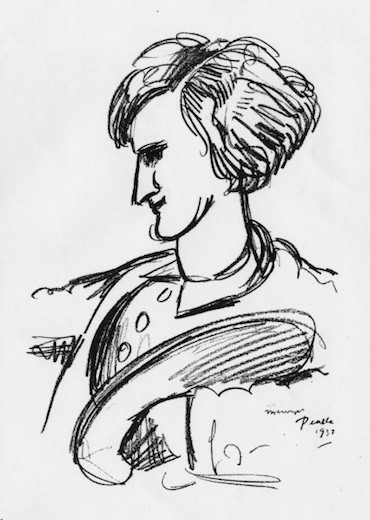

Mervyn Peake drew Diana Gardner in 1937. She was 23. He was a teacher of life-drawing at Westminster School of Art, where Diana, and Peake’s future wife, the painter, Maeve Gilmore were fellow students. No beauty, Diana Gardner has an interesting, strong face, hard to reconcile with Virginia Woolf’s later description of her as ‘rather brow-beaten’.

The Woolfs and the Gardners, Diana, her brother and her widowed father, Major Gardner (ex railway engineer, Malaya), were neighbours in Rodmell during the war. Virginia, who had little time for the local gentry, complained in her diary on 9th January 1941, ‘Miss Gardner instead of Elizabeth Bowen. Small beer’, and, finding herself in the same compartment on the train to Brighton, left the aspiring young writer in no doubt , ‘she didn’t want me in the carriage … I was a nuisance’. She was kind enough, nevertheless, to add an initialled note of congratulation to the Horizon pre-publication contents leaflet listing one of Diana’s stories. We do not know if she read the story, or what she thought of it if she did (the mutual dislike that existed between the editor, Cyril Connolly and Virginia Woolf may not have helped). The leaflet was announcing the Christmas 1940 issue of Horizon: the story was ‘The Land Girl’. No mean feat for the ‘brow-beaten’ daughter of a ‘sheep-witted’ (VW’s description) father, to have her first published short story appear in a prestigious literary review, between George Orwell’s essay, ‘The Ruling Class’, and ‘Civilians at Bay’, notes from wartime France, by Brian Howard. Diana was twenty-seven.

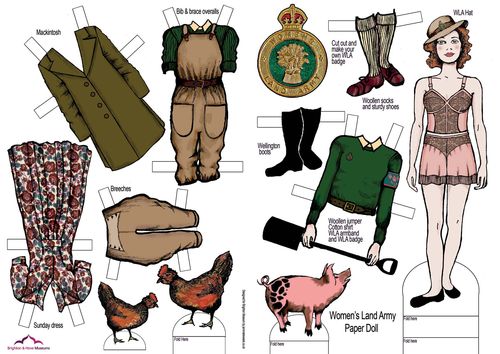

Apart from the title story, ‘The Woman Novelist’, all the stories in the collection were written and almost all published during WW2, but the majority make slight, if any, direct reference to the War. Apart from a group of Nazis meeting for their annual dinner and a young Storm Trooper (three of the stories are set in Germany), only one character, the eponymous Land Girl, has a clearly defined, uniformed role and her war effort is directed not against the Germans, but against her own personal enemy: the farmer’s wife who is sparing with the sugar at breakfast. Una’s revenge is carefully planned, brilliantly executed and ruthless and the catastrophic outcome surprises even her. It is a darkly comic story, told in the clipped, heartless voice of the quite outrageously self-centered Una, a young woman with a past, that may or may not have been unhappy: Diana Gardner drops the phrase ‘my guardian’ into the first paragraph, and lets it hang.

In all of these short stories, her use of incidental detail is masterly (is there a feminine form?). Some, like the reference to the ‘guardian’ are left in the air, shadowy clues to past or future. Others deliver swift ‘pen portraits’, wittily compressing whole paragraphs into a few brilliantly chosen words. She introduces a husband (in ‘The House at Hove’), ‘making a survey of metal deposits in a piece of out of the way country near Hull’ and (wordlessly) invites us to compare him with a lover who ‘had travelled all over Europe making a collection of miniatures’, the cold and dull with the exotic aesthete; and a thoughtless, unimaginative brother (in ‘No Change’) ‘who had gone to India, in jute, while still a boy’, ‘in jute’ – so narrow somehow. We need know little more about a young woman whose ‘nails were crimson and faintly stained with nicotine’ to be certain that she will prove an unsuitable companion with whom to embark on a lengthy and potentially dangerous sea voyage (‘Crossing the Atlantic’). ‘Margot dug her elbow into a cool place in the duvet and turned the page of her novel. She had bought it on the day of publication in a bookshop in the rue de Rivoli, eager to possess it, but now she found it almost boring.’ What a raft of information Diana Gardner gives her reader in the opening sentences of ‘The Summer Holiday’: weather- hot, probably mid-summer, June; location – Paris; character, Margot – a reader, impulsive, easily bored.

Some details flesh out incidental characters, a gap toothed child, a tortoiseshell cat, a child’s ‘faintly irritating voice’, while others are included to sow seeds of unease: a waste-paper basket full of old letters, whose content even by the end of the story (‘The Couple from London’) we can only guess at. Miss Carmichael’s ‘thick dark hair (which turned out later to be a wig’: we are not told when or how this is revealed, but with one deft stroke, Diana Gardner adds another, inexplicably, worrying detail to the island setting of ‘Miss Carmichael’s Bed’. We are convinced, that we are reading some kind of mystery story, a horror story perhaps. But she has laid false trails.

A twist in the tail is generally considered to be a feature of the most satisfying short stories. In ‘Miss Carmichael’s Bed’, and later in ‘Mrs Lumley’, Diana Gardner does more than twist the tail, she forces us to reconsider not simply the narrative, but the genre: it turns out that the first is not a mystery story, nor the second a ghost story.

‘She wondered if Mrs Lumley’s James had slept here … What’s it got to do with me what happened years ago.’

There is humour in the darkest of the stories, and a certain sadness in some of the ‘lighter’ ones. Some conclude almost in bathos, while others end far more dramatically than we could have predicted. Relationships hang by the flimsiest of threads. A parent might disappear or die – we should remember that Diana Gardner lost her mother when she was only nine. A wife (and it is usually the women) might leave on a whim: the Grahams’ summer holiday and their marriage (‘The Summer Holiday’) end abruptly when they disagree about the danger that they face from the German invasion of France: ‘She felt that they were beginning not to understand each other’ – a lovely example of Gardner’s understated wit. The woman novelist of the title story and her husband stay married not for love but for the sake of her career, on which both, for quite different reasons, depend. A comically ill-matched misogynistic man and an ambitious woman find themselves thrown together for life by circumstances and an elaborate practical joke, after a ghastly Atlantic crossing. A shepherd’s wife has ‘long ago conquered the jealousy she once felt when her husband chose his sheep before his children’ and doesn’t complain when he leaves the family cottage, threatened by German incendiaries, to mind his flock.

‘There are places on the South Downs where the walker suddenly comes upon a cottage, or pair of cottages, puritanical in shape and usually built of flint and brick, with a slate roof – the ‘council house’ of seventy years ago.’

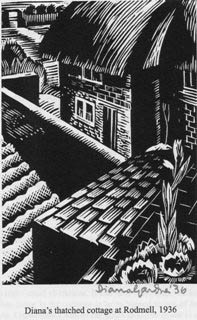

Voice, black humour, economy of means, the unelaborated detail, and the twist in the tail: to these classic elements of the short story – and how hard it is to write about them while avoiding spoilers – Diana Gardner, a water-colourist and wood engraver as well as a writer (there is a delightful young painter among her characters), adds some startling dashes of colour, not least in the ‘German’ stories. An increasingly unpleasant young Storm Trooper (‘The Splash’) is memorable for the blond curls on his chest; Nazis arrive along a forest path for their anniversary dinner (‘In the Boathouse’), ‘against the pale greens and browns of the trees their mustard-coloured shirts and black breeches made them look as if they were made of cardboard.’ A lake (‘Summer With the Baron’) is ‘dark peacock blue’, the bathing huts ‘warm umber’ and the bathers pinkish-brown’. One can almost picture her palette.

Virginia Woolf found Miss Gardner ‘amiable and silly’. Perhaps she underestimated her young neighbour.