‘There was something strange and deep about being sisters’. Three sisters, three marriages, two families producing two more pairs of sisters, as different from one another as their mothers and aunts, the cast of They Were Sisters is wide and varied, in personality, in age and in back history. Dorothy Whipple who rightly prided herself on ‘doing people’, gradually reveals her characters, turning a forensic eye on their flaws. In his nightly monologue to his eldest daughter Mr Field regularly refers to what he calls ‘a strain of wildness and of weakness in the family’. ‘From your mother’s side, you understand,’ he insists ‘Not from mine. My people, Lucy, are and always have been a steady, upright, God-fearing lot.’

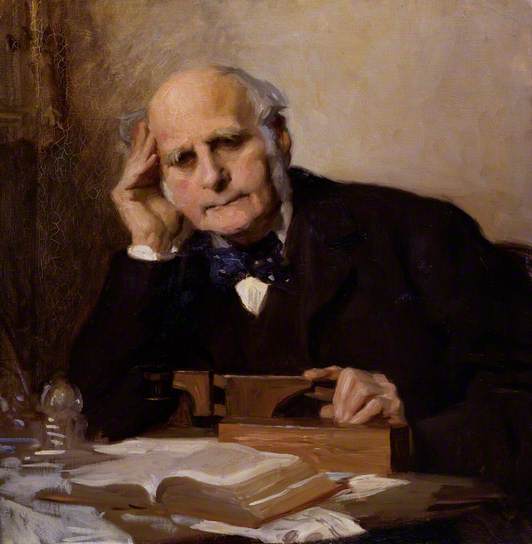

The novel opens a year or two before the start of the First World War, when the nature v. nurture debate was very much in the air. Lucy Field’s father’s talk of ‘strains’ suggests that he is not unaware of it. The First International Congress of Eugenics took place in 1912. When Dorothy Whipple began writing They Were Sisters in 1939, the works of Sigmund Freud were becoming known in England. The novel encompasses both, suggesting that while destiny is largely determined by heredity, childhood experience has its part to play for better or worse in forming the adult character.

Mr Field is convinced that his younger daughters have inherited the ‘bad’ maternal genes. Following the sudden, untimely death of their mother, he requires of Lucy that she share with him the ‘necessity of watching continually over the girls’. Lucy is eighteen, Charlotte thirteen and Vera eleven. It is a heavy responsibility and she must bear it for the rest of her life. Her father believes her to be the steady one. She was certainly strong: defying convention and against his will, perhaps encouraged by her mother (and in a fleeting display of wildness?), she had chosen to work for a scholarship to Oxford, rather than peg her future to marriage. Her mother’s death put paid to the dream, forcing her to become a surrogate mother to her siblings, and reluctant companion to her widowed father.

No such sacrifice was demanded of the three boys. Their father did not consider it necessary that they be watched, merely ‘kept straight’. When even that proves impossible for the two eldest, pleasure-seeking ne’er-do-wells, too similar in character to their maternal forbears, or perhaps shaken by the war, they are dispatched to Canada, with a large lump sum each. Out of sight out of mind. Wild or weak? The youngest, and steadiest, is chosen to head the family law firm, but not the family. Jack is not asked to share in the watching of his sisters and remains a shadowy, possibly lonely, figure throughout the novel. If he has needs, they are none of Lucy’s concern.

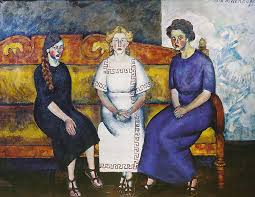

Her enduring commitment is to her sisters. Charlotte, pretty but weak, and Vera, beautiful and wild, would be ‘her responsibility, her anxiety and her happiness.’ Would Charlotte have been stronger, or Vera more measured had they not been bereaved so young, had their mother lived, gently to guide their growing up? Lucy does her best, but not without some resentment. As a young woman, during their dancing years, she finds herself more chaperone than contemporary, ‘like a barn-door fowl watching two swans she had brought up take to the water.’ Eclipsed by her prettily shod, fair-haired sisters, Lucy, whose hair is dark, untidy and unfashionably long, deliberately deters her (few) potential partners by sticking her feet in brogues.

Much later, nearing middle-age, she is still wearing them; ‘it was as if she had remained stationary in her brogues while they had moved on and away.’ But if they have moved on and away, it is in disastrously wrong directions; if she has remained stationary it is because she has settled in the right place, with the right person. The ‘oddest man she had ever met’, scruffy, undemonstrative, and uncommunicative (something of a relief after the verbosity of her father), William is kind, and loyal and loving and (relatively) tolerant of his sisters-in-law. Childless and outwardly lacking in passion, it is nevertheless a marriage seemingly made in heaven – Lucy, a devout Anglican, would surely think it so. Good luck, or good management? Lucy does not venture an explanation of how people select their partners, but fiercely contends that the conduct of our lives depends on the people we live with.

Although he differs with Lucy as to the extent to which our choice of partner determines our lives, William agrees that Brian Sargent is ‘too good’ for Vera – he doesn’t ask why, from an incalculably large field of suitors, she picked a man who was tall and handsome but, even by his own mother’s reckoning, dull – and admits that Charlotte’s husband is ‘not good enough’ – a startling understatement which comes nowhere near describing Geoffrey Leigh’s sadistic cruelty. Whipple doesn’t spare her reader. The graphic depiction of the home life (if it can be called that) of Charlotte and Geoffrey, and of his calculated cruelty towards his children, is almost unbearable.

She leaves us in no doubt about the evil in Geoffrey’s soul, but she searches for its roots, exposing behind the attention-seeking, domineering bully, a fatherless child, doted on by his mother and sister. On the surface he and Charlotte make an obvious fit: the weak woman seeks a strong man, the strong man with a desire to dominate looks for a weak woman. But there is a deeper similarity between them: an element of arrested development. Both lost a parent in childhood. Geoffrey hates the fact that the time for pranks and boyish japes is over, that his contemporaries have outgrown him, that mood swings, forgiven by a fond mother, are unacceptable in an adult. Though not the youngest, Charlotte liked to be thought of as the baby of the family. Only after more than ten years in an abusive marriage does she become an adult, ‘but at what cost!’, writes Whipple. ‘It doesn’t do for some people to see clear; they can’t stand it.’

Brian and Vera, too, are examined through the ‘post-Freudian’ lens. Raised by a strong mother who, we later discover, finds him boring, he marries a strong woman (who also finds him boring), and turns into a weak husband, but a (sporadically and ineffectively) dominant father. Vera, wild Vera, believes she wants the freedom offered by a doting husband. Was she allowed too much freedom as a girl? Did her beauty make life too easy for too long? Her mother-in-law considers her too beautiful: ‘Brian would have been better, we should all have been better with somebody plainer. They say beauty is a gift, she thought, but it makes a lot of trouble. It sows dissatisfaction, a kind of yearning all around it …’ Only when Vera’s looks begin to fade is she forced to bend to the will of a man she loves (for the first time) more than he loves her: to grow up, in short – still with a chance of happiness, unlike poor Charlotte.

![‘He [Brian] thought he ought to see something of them every day, since their mother saw so little. He read aloud to them at this time. Not that they cared for it, but he thought they ought to. ... At the moment he was reading the Just So Stories.’](https://persephonebooks.flywheelsites.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/JustSoStories-1st-edition-1902.jpg)

In spite of what he sees of the lives of his in-laws, William does not share Lucy’s belief that our happiness hangs on those we live with. He holds that ‘there are other things in life’. For men maybe, but in the 1930s precious little else for women. For those who didn’t marry, the future could be bleak indeed; those who did, discovered that the right choice meant a happy life, the wrong choice a wretchedly unhappy one, from which there might be no escape. Things were different for men. Just as Lucy’s wayward brothers were able to forge new lives in Canada, so Brian, having, predictably, lost one wife finds another, far more suitable (more boring), and resettles in America. Even the dreadful Geoffrey, having driven Charlotte to drink, drugs and an early grave, can take off with the daughter he loves (and tyrannises). Even in the next generation, the daughters must mostly struggle to get within striking distance of their dreams, while the one boy is able to break free early. Running away to sea was nowhere on the list of options for Stephen Leigh’s sisters. Would it be now?

For good or ill, and limited though their choices might be by circumstance and their own characters, women choose their husbands, but they don’t choose their sisters. Considering the yawning gap between herself and her older sister, Margaret, Charlotte’s daughter, Judith, reflects that ‘when the time came to part, they felt an almost painful tenderness for each other.’ Her mother and her aunts might have said just the same. Between the Field sisters, widely different as they are, widely as their paths diverge, however infrequently they meet as adults, and however unequal they are when it comes to giving and taking, the ties remain, strained but unbroken. Vera who goes reluctantly and late to Charlotte’s deathbed, nevertheless spends long hours on her knees holding the dead woman’s hand, and she and Lucy are able to hold and comfort each other – a comfort that will not be extended to (or expected by) their brother Jack.

And what of the sisters of the next generation? Judith and Margaret find an unexpected closeness, but face a far wider physical separation than their mothers, living like Sarah and Meriel, Vera’s daughters, on different continents. Will Lucy, the only childless sister, manage to forge a new family, bringing together under her roof her two nieces, the cousins Judith and Sarah? What genes do they carry? Has the weakness or the wildness taken hold? Has Judith inherited her mother’s fatal flaw, her alcoholism, or her drug habit? Worse still, could her father’s sadistic streak be in her? Is Sarah, so clearly her ‘mother’s child’, demanding and difficult (her staid, dull sister, so obviously their ‘father’s child’ ), still young enough to benefit from Lucy’s steady focused fostering? Will nurture prove stronger than nature?