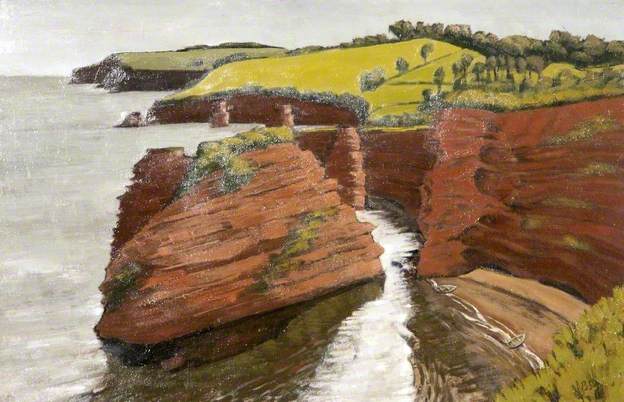

Relinquishing a prosperous, if bohemian, pre-war life in London for a ‘conchie’ commune in Devon, Margaret Bonham honed her pen on these vignettes of village life, with an occasional glance back to London, Bath, and the North coast of France.

Divorced from a ‘card-carrying’ pacifist of the 1930s, and newly married to a Second World War conscientious objector, Bonham’s war, to judge by this collection, was very different from that of other Persephone authors, Mollie Panter-Downes, Jocelyn Playfair, Elizabeth Berridge, or last month’s Barbara Euphan Todd. There are no bombs, no obvious shortages, no queues, no evacuees, no on-going rationing. The spirit of make-do-and-mend is noticeably lacking. Indeed a positive aversion to it is a shared by the strongest and most independent of the women. Lucy in ‘The Two Mrs Reeds’ – the closest, according to Bonham’s daughter, to a self-portrait – who is ‘not much interested in other peoples’ children’ and likes ‘the wrong kind of house’, does not knit, nor does Emmy, in ‘The River’, a free spirit, with advanced views on child-rearing, who also refuses to make blouses out of curtain lace. Only a few oblique references and small but telling details set these stories in their time: a WAAF officer in uniform, maternity hospital visiting hours relaxed for serving fathers on leave, Utility tables, a lasting reminder, along with the County War Agricultural Committee and ‘an indefinite number of white babies and three black ones’ left behind, along with ‘a way of dancing, a way speaking’ by departed soldiers (‘Inigo’).

American soldiers have departed, English soldiers have not returned. Not until 1951 would the balance of sexes right itself, and then only for the under 30s (see A Woman’s Place by Ruth Adam. Persephone Book No. 20). This is a world from which, with one or two vivid exceptions, men are absent.

Women make up bridge fours and dance with each other. Children (mostly girls) are cared for by mothers alone, aunts, grandmothers or eventually strangers. The relationships are not for the most part warm. A mother nurses unattainable literary ambitions for her daughter, a precocious daughter bossily tries to educate her mother, a wildly imaginative three-year-old, having exhausted her mother, sees off a mild but tiresome minder: Miss Jenner, a clergyman’s daughter, vainly tries to tame the child (‘I aren’t Britta … I’m a bull’) with whimsical stories of fairies in flowers (‘…all children are alike you know – they all have these charming fancies.’), only to find her fancy trumped, when Britta plucks Miss J’s little red fairy, with little green wings from inside the japonica petals, and stamps on it. ‘I’ve killed it’, she says grimly, before setting off on an imaginary, but nonetheless awkward, bicycle.

Grown-ups, with their affectations and their need for secrecy, are rarely a match for children, who continually baffle them with their straightforwardness and their capacity to live in and for the moment. Even the most caring and sensible parent, an ‘older father’ in ‘The River’, whose weekly walks along the riverbank with two-year-old Frankie, provide delight for them both underestimates his small daughter’s resilience. William moves heaven and earth (almost literally) to replace an old shoe and a marrow, much loved riverside flotsam swept away in a flood, and is astonished, almost disappointed, to find her unimpressed by their reappearance: what Frankie misses is the thrill of the rushing flood water. And this is a father, who like his wife, and one must assume the author herself, believes that ‘children have more sense than they are credited with’. Only such confidence in the hardiness of children can explain the apparent contradiction between Margaret Bonham’s two year long abandonment of her own children and her acute and sensitive insight into the workings of young minds.

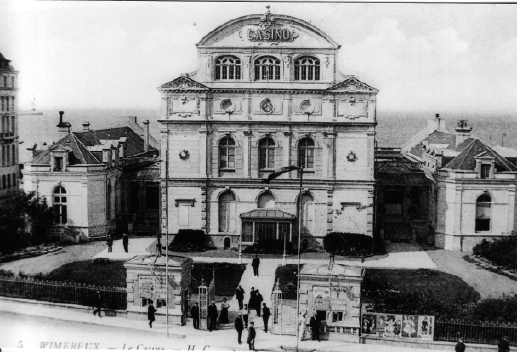

Anxious Joe, takes courage from his overbearing father’s broken revolver, shows unexpected (almost excessive) cool headedness at the scene of a bloody train derailment, then, no longer the hero of the hour, regresses to boyish excitement reliving ‘with ecstasy’ the moment of the crash. Bonham sees this as natural, and she may be right. Her psychological acumen is evident, although not overplayed, in the title story. Three English girls with their French friend, all in their late teens, obtain permission to go to Casino. Kitty the eldest and most eager, is, inevitably, disappointed; Rhys is a nervous and reluctant participant in such a perilous adventure. Only Valentine fully enjoys it: a young painter, content to observe, is thrilled by the colour, the clothes, the lights.

Valentine has the author’s eye. Bonham’s images are brilliant: ‘the water in each hollow, fringed with brown weed, was clear as gin’; the sea, ‘the same milk blue as the sky, but polished with light’; a woman ‘walks in her bracken tweeds as undisclosed and uncompromising as a moving piece of country’. ‘… a diamond brooch as big as a saucer lay so flat on her bosom she could have put a cup on it’, conveys the size of the jewel, the stoutness of its wearer, and wittily suggests the vulgarity of both. Bonham rarely wastes a word. Invited to share his fiancée’s delight in the countryside, a temporarily uprooted London businessman replies, ‘ “Charming” … flicking towards the river the kind of glance he would have awarded a gasometer’. His impatience, his lack of sensibility and his preference for the dully functional over the natural, and the incompatibility of the couple are all there. An unexpected juxtaposition of words speaks volumes: a house has ‘the charm of stark architectural lunacy’ (‘Inigo’); little Britta’s mother shuts the child’s door, and leaves holding an imaginary hedgehog in her hands with ‘absent care’. At the bridge table, ‘the married couples, on bidding but hardly speaking terms, began another rubber’ (‘Annabel’s Mother’). Even punctuation is used with rare comic effect: ‘… Lucy felt a little more amiable towards Thomas; but not much; she could not forgive the caravan.’ (‘The Two Mrs Reeds’).

Bonham has little time or sympathy for sentimentality. Romance occurs somewhat fortuitously, marriages are made for motives of practicality: a couple brought together over a cat, another over an abandoned baby. The history of poor Mrs Greene’s married life is summed up in less than half of the opening paragraph of ‘The Blue Vase’, and it is hard to avoid a cruel smile when we learn that Mr G. ‘had first begotten a child and then collided with a lorry.’ The humour is not kind, but it is seductive and it is (relatively) even-handed, aimed at Chelsea intellectual poseurs as pointedly as it is at the pettinesses of village life. At their best these are stories which stand comparison with some of Saki’s, and, for twists in the tail, O’Henry’s.