Young Anne, the last of eight to be published by Persephone, was Dorothy Whipple’s first novel. Surely no Persephone reader will be coming to this without having read some or, more likely, all seven (and the collected short stories).

Going back to the beginning is like turning to the early pages of a photograph album. Familiar with the kindly, open face of the older woman, would we recognise her in the young Dorothy? The young woman, perhaps in her thirties, is more demure, more self-conscious, a little less confident, but the piercing gaze and the dimpled chin, are there, and a smile about to break, a desire to engage. We open Young Anne looking for intimations of the novels to come. And we are not disappointed.

Young Anne was published in 1927. Dorothy Whipple was thirty-four. Her first and great love, George Owen had been killed in the first week of the War, and in 1917 she had married Henry Whipple, twenty-four years her senior. Her (precocious) literary career had begun some twenty-two years earlier. She was a regular contributor to the ‘Children’s Corner’ of the ‘Blackburn Weekly Telegraph’, where more than forty of her short stories appeared between 1905 and 1910, when she left her convent school, and, more or less, stopped writing. We can only conjecture as to her reasons for giving up, and for starting again nearly twenty years later. Was she motivated by Henry Whipple, perhaps because they had not had the children for which they had hoped?

Largely autobiographical, Young Anne has at its heart the moving account of a writer’s apprenticeship, a precocious beginning, a sudden unhappy laying down of her pen, and an eventual return many years later to her desk, encouraged by her husband, eighteen years older than her, and a man of few words, ‘Work’s the thing … It’s time those notes and tales were turned to account. Time you began to hack them into shape.’

In a typically succinct opening chapter, Whipple introduces the ‘cast’, gathered in church, each family in its own pew, seen first through the innocent gaze of her eponymous five-year-old heroine, chewing the top of the pew, her hair coming ‘diffidently out in tendrils of gold, and puzzling (as we all did at her age) over the requirement for a green hill to have a city wall. Great-Aunt Orchard, has ‘a face like a cat, complete even to whiskers’, and purrs at clergymen. ‘Out of sight at the end of the pew was Jane, the maid. Aunt Orchard always took the maid to church on Sunday mornings. The maid didn’t seem to like it much.’ Out of the mouths of babes … Vera Bowden, her niece, has a ‘red, red mouth, an exquisite lace frock, gold bangles and pearls’. She also has a new wedding ring, something the child might have missed, raises her dark lashes and smiles across ‘at Charlie Brookhouse, to whom she had once been engaged’. Note the comma – a barely perceptible pause, just time for the writer to raise an eyebrow, a nod and a wink to her reader: Mrs Bowden, we understand, is trouble. Whipple fills us in a little on Aunt Orchard too: this pious monstress has ensured her position of respect in the Parish, giving ‘the reredos, the East window and part of the pulpit in memory of her husband, Ephraim Orchard’. A lesser writer would have had her give the whole pulpit.

The little girl looks over at the newly-rich Yateses: Mr James Yates, a small and highly-polished person, with a neat, round stomach ‘festooned with gold watch chain, which reminded Anne of the looped railings round the bandstand in the church’. The bust and hips of his wife are ‘encased in an expensive silk dress. She wore a feather boa and tight white kid gloves.’ Mrs Lockwood (Because of the Lockwoods. Persephone Book 110) similarly stout, wears a ‘tightly-fitting pink gown with the ospreys waving’ and has small puffy feet, like marshmallows. The Yateses are the prototype social climbers, of whom we will meet many more in Whipple’s later novels, and of whom she is consistently unforgiving.

Long before she could form her letters, sharp-eyed little Anne Pritchard was making mental notes. With a stubby pencil, in the unused pages of her brothers’ old exercise books, she had written her first stories before she was ten. On her tram journeys to her convent school, she observes her fellow passengers, ‘the woman with a face like a frog, all merged into neck; the man with the thick face, who led, she was sure a greasy life and liked fat pork with slodgy stuffing …’ ‘Let me remember,’ wrote Anne in a very private notebook. ‘To dwell on the bald heads, the heave of the stomach, loose necks of middle-aged men. Let me point out their tooth-picking ways, their eructations after food.’ The notebooks will be the novelist’s source material, a solace at times, and much later, ‘her safety valves’.

A visit to the hairdresser is a writer’s field trip. Madame Juliette, hairdresser (and occasional poetess – ‘she wrote chaotic verses which appeared at times beside Anne’s tales in Weekly News’ ) pauses with the hairpins and wisely advises against early marriage, ‘establishing herself as a personality, thrusting herself on Anne’s consciousness.’ ‘Strange how people were always doing that’, reflects Anne, the budding novelist, observing, listening, picking up telling details, imagining the back stories, and tucking them away for later use. Madame Juliette ‘believed that each soul had its affinity, and had hers in the shape of a little tailor in the shop downstairs. He was, of course, unhappily married.’ The hairdresser who plays no more than a walk-on part, is brought to life in that one detail, one stroke of the pen, the inevitable cliché of her plight captured in the ‘of course’, slipped between commas.

Whipple made no secret of the fact that she was more interested in character than in plot, and the plot of Young Anne is, as Lucy Mangan says in her introduction slight. What interests Whipple, and what drives this novel and later ones, what makes us want to turn the pages, is our need to know how people, in whom we absolutely believe, turn out. Good or bad, will they get their just rewards? Fulfilment, or comeuppance? Their cards are marked from the start. Alongside Anne in the pew is her father, dyspeptic, cross, and thin – the author’s prejudices on body-mass were already well entrenched. Olive Pritchard is vague, self-absorbed, and happy to leave the care of her daughter, and her two sons, along with the running of the house to Emily, their maid-of-all-work, who willingly shoulders the task ‘of running the house, of keeping Gerald in his place, Anne out of scrapes, Philip from overeating, of coping with her mistress’s indifference, her master’s indigestion and his righteousness’. In one sentence the young Whipple sums up the family dynamic: no surprise that a click on ‘Family’ under Categories on the Persephone website brings up every one of her novels.

Emily is a kind and generous woman. It will be with her encouragement, and, in a reversal of the social order (Whipple fans will recognise the theme), her financial assistance, that Anne is able to enter the world of real work, escaping the tyranny of Aunt Orchard, on whom circumstances have left her dependent. With an abundance of native intelligence, and good judgment, Emily Barnes is the precursor of Nurse Pye and Miss Vanne in The Priory (Persephone Book 40), of Carrie, the barmaid and part-saviour of the Blakes, in They Knew Mr Knight (Persephone Book 19), Oliver Reade, the self-educated, hard-working market stall-holder in Because of the Lockwoods. Emily like her siblings-under-the-skin, would seem to have come into the world fully formed, endowed with good judgement, a capacity for hard work, and no sense of entitlement, free of what Jeanne in Because of the Lockwoods calls ‘the malady of the ideal’.

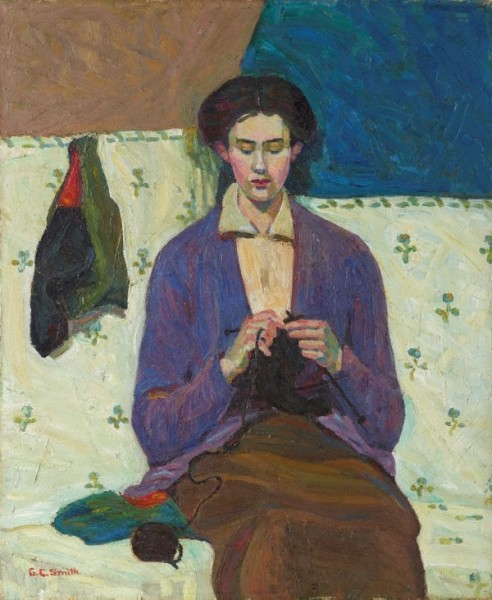

“The Sock Knitter” by Grace Cossington Smith. NSW Art Gallery.

If Young Anne is about growing up, it is also about giving-up, letting go of unrealistic dreams. ‘It is one of the properties of youth to be forever building out of its imagination innumerable palaces wherein to dwell, and to accept them later for the mud huts they turn out to be.’ Whipple’s message, her credo, is that we must learn not merely to accept the mud huts, but to make the very best of them, to adapt to living in them, accommodating the dream to the reality. We should not expect this to be easy. Work, as Anne’s husband, wisely advises, is the thing