This multi-faceted, fundamentally dark novel, struck me at first, I confess, as a mixture of Enid Blyton and Ivy Compton-Burnett. In an amusingly unconventional family, four sisters, a fifth having married and left home, are left to their own devices in a large country house, which has seen better days. They cope with kitchen disasters, enjoy sisterly chats after dark, unsanctioned trips to the cinema, and the local tea-shop, while lightly supervised by their writer father, with occasional interference from their beautiful, remote, mildly dotty mother. A cosy read, until we remind ourselves that bright dialogue can masquerade as communication, and veil troubling secrets. Eccentricity can be the acceptable face of borderline insanity.

Guard Your Daughters opens some time after the sisters have gone their separate ways. Morgan, the middle daughter, narrates the months leading to the break-up of a once seemingly tight-knit family. Defensively describing the Harveys to her London friends, Morgan says, ‘We were queer, I suppose, and restricted, and we used to fret and grumble, but the one thing our sort of family doesn’t suffer from is boredom.’ Every unhappy family is, as we know, unhappy in its own way. That the closeness was pathological only gradually emerges. Morgan, her sisters and their father have contrived to maintain a semblance of normal family life against lengthening odds, holding together a fissured unit, their mother’s fragility being the glue. Her account is personal, partial and full of gaps. It is also frequently very amusing.

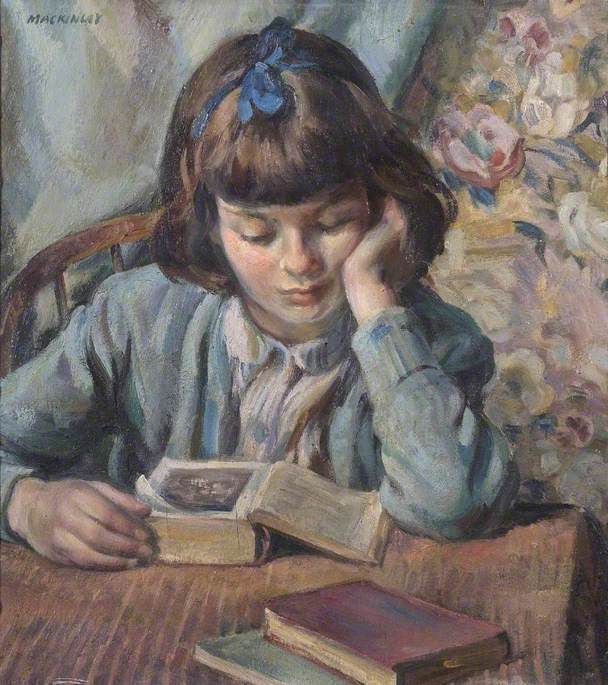

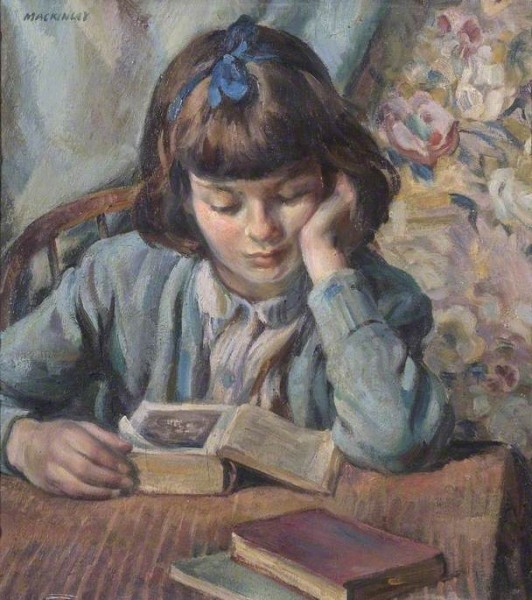

The Harvey sisters are not children. Pandora, the eldest and the only ‘grown up’ is twenty-one. Teresa, the youngest, is fifteen. Inbetween are Thisbe, the ‘poetess’, Morgan the ‘pianist’, Cassandra, cook and kitchen-gardener. Governesses have come and gone in the past, but Teresa has relied on her own eclectic and age-inappropriate reading, with some erratic musical and literary input from her sisters and, even more erratically from her mother. The children of lovers, according to the proverb, are orphans. Though Mrs Harvey’s emotions are unclear, Ted Harvey’s love for his wife is beyond measure. He has done his best for his daughters, but his wife has always come first. His daughters have had to fend not only for themselves but also for him, and for their mother: grazing round the pantry for themselves, putting soup on a tray for her, tea on a tray for him. So many trays, so many lonely meals. Years of fending haven’t honed their culinary skills. The girls share the chores, but none seems to be rostered to shop.

Our suspicions that the Harveys have known far better days are confirmed. Describing a comically irregular game of French cricket, arranged to give young Teresa a taste of team games, such as she might have enjoyed were she ever to have been to school, Morgan recalls a time when the tennis lawn was a well-kept court, where Father and Mother, in white flannels and pleated skirt, would entertain friends on Sunday afternoons, home-made lemonade was served from little pink tumblers, and the children were called in at six-o’clock by Nanny. There were three servants then, a car and a telephone. Now plantains and daisies have taken over the lawn, the few remaining tumblers gather dust on a high pantry shelf, nanny, the servants, the car and the telephone all gone, and no friends visit.

What is going on? Post-war changes in life style were common to all, and to an extent disguise what is happening behind the Harveys’ rusty gates, where wartime shortages have segued into prolonged belt-tightening: for reasons which become clear only towards the end of the novel, although their father is a successful writer, money is short. Retreating further and further into a comfortable eccentricity, the family have come close to isolating themselves almost completely from their neighbours. When on separate occasions two young men make it past the gates, let in the light, and disturb the peculiar equilibrium, a kind of spell is broken.

Morgan struggles to see her mother ‘with stranger’s eyes’ … ‘but I loved her so much that it was difficult. There was a little smile on her beautiful, drawn face, and she was singing a very sad Hebridean song, quietly, and rather flat … Mother didn’t see us at first, and she was so graceful and aristocratic in her funny old clothes that I hated to disturb her.’ Morgan’s love is both tender and protective, but she doesn’t demur when Pandora describes the family as ‘odd’, nor question Thisbe’s explanation for their unusual names, ‘“Mother chose them all except Teresa, and by then she’d got tired, so father had a go.”’ Tired is an odd word to use. What is Thisbe saying? When her Mother is taken up to bed by Father, distressed by discussion of Teresa’s education, Morgan is certain that she will ‘take one of her tablets and go to sleep’. We begin to understand that this is their ‘normal’.

Pandora who has dared to raise the question of schooling, urges Morgan to leave home. ‘”You know, I couldn’t possibly … it would be – well, almost murder.”’ Morgan does not speak openly of the problem, but she does not minimise it, and seems relieved when Pandora confides that before marrying she had consulted a doctor and been assured that ‘”there was absolutely no reason why we shouldn’t all marry and have lots of children.”’ Although neither sister refers directly to their mother’s ‘condition’ – not even mentioning the word eugenics (fashionable at the time), we understand what they are talking about. ‘“Did you tell him everything?”’ asks Morgan. ‘Everything’? Perhaps the conversations in the steamy bathroom have not always been as light-hearted as Morgan implied. Or have the sisters always carefully and deliberately avoided talking about their mother? Whatever information they shared, or supressed, it becomes clear to the reader that for a long time, since Teresa was born, maybe longer, the family has been quietly adapting not to their mother’s whims, but to her needs.

‘“You’ve known for years what very serious consequences might come of an upset to her. You know what Doctor Gerard has said about her.”‘ Ted Harvey’s argument against sending his youngest daughter to school is firm but gentle, until pressed by Pandora:’“dear Doctor G. isn’t a mental specialist.”’ Then he pushes the genie firmly back in the bottle and stoppers it: ‘“Are you seriously suggesting that I should call in specialists to pry into her private thoughts and feelings? This is a humiliation to which I will not have her subjected. They might even – they might even want to take her away to some sort of Home, so-called.”’ So sad, when what he wants, and works for is that the house they all share should be home.

Morgan shares his hope, and his delusion. Confidently (or blindly optimistically) she affirms that Mother will ‘get better some day’. If we assume her account to be true, which is not beyond doubt, her love for her mother is second only to her father’s. She recognises Mrs Harvey’s ‘clouds’, when others don’t. Reminiscing, long after the family has split apart, she poignantly describes her memories and regrets: ‘Sometimes, too, she would walk for a few yards with her eyes shut, and her lovely tragic face turned up to the air, as though its touch upon her brought peace. Oh, darling, Mother! If only I could have come near to her, could have understood her sorrowful isolation and relieved it with my love.’

I have to disagree with the comment quoted in the afterword that she is ‘a remarkably dull narrator’. Morgan’s insight into the family is as clear as it could be given the constraints of secrecy imposed by their father, and by their class. She is not unaware of the oddities of home life with the Harveys, never self-pitying, and her eye is as keen as her ear for the social comedy she observes on rare forays beyond the rusty gates, whether it be the local Sunday School, or the cocktail party at the house of local grandees.

All the sisters, are strong and resilient, finding a sort of solace and escape in things that they are not especially good at: poetry, music, cooking and veg growing. They look out for each other. But Morgan more than any of them is a true Persephone heroine. ‘We’re all frightfully happy,’ she lies stoically. She may overestimate her looks and her musical talent, but she never dwells on her undoubted courage or her ability to laugh through tears. And we sense in her the strength in the end to move on: ‘… we shall never really be a family again. That part is done, and it was everything while it lasted.’ The future lies ahead, more ordinary perhaps, but easier to navigate.