On the evening of 18th July 1944 André Amar left the Paris flat where he and his wife Jacqueline were living with their 9 year-old daughter Sylvie, for a rendezvous with some fellow members of the Jewish Resistance Movement, and didn’t return. On that day Allied troops who had landed in Normandy on 6th June were fighting for what remained of Caen, moving South and East. They were to reach the capital a month later on 18th August, finally liberating the city on the 25th. Jacqueline’s diary begins with André’s disappearance and ends with the liberation, five weeks during which the Allies are moving towards Paris and her husband, if he is still alive, is most likely to be on his way to Germany.

Snippets of information as to André’s whereabouts reach Jacqueline, by word of mouth, and are mostly inaccurate. He’s being held at Cherche-Midi, he’s at La Santé, at Fresnes, at Drancy: the Germans had filled the city’s prisons, the last and most dreaded being the final holding camp for Jews awaiting deportation by train from the grim station of Bobigny to ‘Pitchipoi’, the catch-all name given by Jews themselves to the concentration camps. She learns the truth on 19th August – and I can make no apology for spoilers. André and his fellow resistants had been held in Drancy. They had not been released when the prison was liberated and evacuated the previous day, but were already on a train heading for Buchenwald. The train, three carriages commissioned with great difficulty by the governor of Drancy, Alois Brunner, in order to effect his own escape, and containing, as hostages for his protection, just 51 prisoners, a few resistants, a number of high profile Jews, and some of Brunner’s personal enemies, had been the last to leave Bobigny, on 17th August.

On the evening of 25th August Jacqueline describes powdering her face, putting on some lipstick, changing into a fresh dress, and watching the celebrations in the streets of Paris – the singing and the dancing and the crowds surging around the tanks, the girls in their best and brightest clothes, the banners, and the flags ‘made out of scraps of material, hastily dyed and roughly stitched’. ‘And yet,’ she adds, ‘so many hearts are aching for someone who is not here.’

A few days earlier she had asked herself why she was keeping the journal: ‘Is it my escape, like my mother’s embroidery? … What has been the point? Who have I been doing it for?’ With excessive modesty she sums up the contents, a few scribbles on some days, several pages on others, as a ‘futile attempt to record events and how it has felt to live through them, to describe my various hiding places, my journeys, the dark hours of the dawn, the sleepless nights.’ The notebooks that make up the first section of Maman, What Are We Called Now weave together a daily diary, an anguished love letter to her missing husband, a personal memoir, and a vivid and personal account by a Jewish woman in her thirties of wartime life in occupied France.

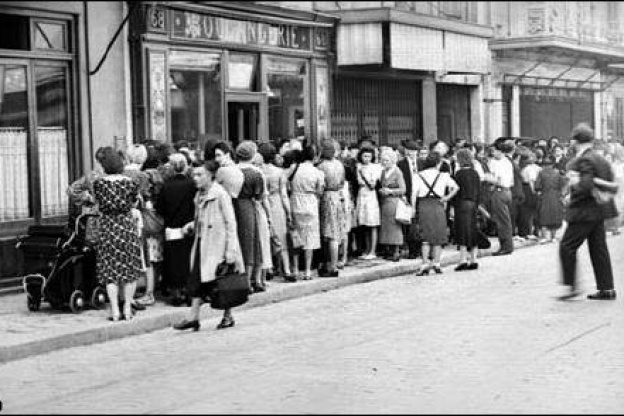

Shifting back and forth from the present to the immediate past, and further back to the First World War, the notebooks intersperse moments of private fear and grief with reflections on a gilded childhood and youth; they describe the privations of war, the struggle to find food, to keep warm, to get around when there are no buses and no metro, to put on a good face for the children; the tiredness, common to all women in war, and the little acts of defiance peculiar to those living under an occupying force – the silent protest registered in continuing to wear bright lipstick, colourful skirts and wide hats. And they record the persecution of Jews in France, and the shameful collusion of the Vichy government.

Jacqueline’s family had been in France for several generations, André’s since the 1920s. Her father was a financier and newspaper owner, his a banker. Both lived in the prosperous 16th arrondissement of Paris and attended the best schools. If Jacqueline was a little envious of her Catholic schoolfriends, with their ancient lineages and old family houses, neither she nor André thought of themselves as any less French. Their Jewishness was not denied but they had never thought to be identified by it. Indeed, they had themselves made the distinction between themselves: Israëlites, from old established families, and Juifs, recent immigrants from Eastern Europe, a distinction that would not be recognised by the Nazis, or the authorities of Vichy France. The path from riches to rags may have been a little longer but the direction was the same: barred from the professions, stripped of their possessions, forced out of their homes, hounded from hiding place to hiding place, desperate to avoid deportation.

The flat in the rue de Seine, from which André had set out on 18th July, was little Sylvie’s ninth home in four years. Marseille, Aix-les-Bains, a village in the Vaucluse, another in Savoie, and more, many requiring a fresh alias: Sylvie’s question, ‘Maman, what are we called now?’ tells the story. André’s arrest meant packing up once again, to be taken in by one of the unsung heroines of wartime France: Nana, a humble shopkeeper, was one of those women, who took in prisoners, escapees, members of the Resistance, Jewish children, doing it ‘for her country’. Jacqueline’s father was hidden for months by the old family cook; her sister and her father’s secretary were saved from arrest thanks to the warning shouts of the concierge and some brave neighbours ready to shelter them.

Serge Doubrovsky a French Jewish writer, who spent almost a year in hiding as a boy with his parents, wrote later that ‘every Jew who survived in France during 1942-4 owed his or her life to some French man or woman who helped, or at least kept a secret.’ It is equally true that many more might have been saved had it not been for petty, often mercenary, acts of betrayal, unnecessarily zealous adherence to regulations, or the choice of some French man or woman to do nothing: the informer who handed over five children in exchange for 4,700F and two packets of cigarettes, the magistrate prepared to preside over the commission for denaturalisation of Jews, the members of the Milice eager to exceed their ‘quotas’ in delivering Jews to the Nazis.

The first part of Maman, What Are We Called Now? ends on a joyful, even optimistic note. Paris is free. Life is still hard, but by August 1944 the men in André’s group have set up the Service des Déportés Israélites, establishing their offices in the Hotel Lutétia, which after VE day on 8th May 1945 would become a reception centre for returning deportees.

For a few months people continued to believe that they would see their husbands, parents, children, grandchildren again. Rumours kept their hope alive: the men had been set to work in the mines, the old kept in hospitals, the children sent out to farms. ‘Pitchipoi’ wasn’t so bad after all. In a chilling paragraph Jacqueline sets out the truth, which was that nobody knew anything:

Not a single postcard had been received not a single escapee had been sighted. The French Red Cross knew nothing: they had barely gone beyond their limited remit, the Swiss Red Cross said nothing other than to convey a bizarre optimism based on reports from the sham camp at Theresienstadt, which had a Town Hall, a Casino …. with dances for the inmates, everything, in short, but a post-office, and which was nothing but a ‘puppet’ camp, set up solely to satisfy the curiosity of the Red Cross Representatives, a curiosity which as it turned out they did not have.

Her rage is palpable.

Angrily challenging General de Gaulle’s upbeat VE Day pronouncement that not one death should be forgotten, ‘no mourning, not one tear shed in vain’, she would remind him that some were mourning not only their war dead, but elderly parents, young brothers and sisters, who had neither the time nor the strength to do anything, ‘whose deaths served no purpose, who did die in vain, who died for nothing … the dead who could not die like soldiers, but were shovelled like bread into ovens.’ And she would have him, and others remember all the children who ‘went in the lorries, so many children, slaughtered because they were unable to work, thrown into the ovens with their mothers, who refused to leave them.’

Many of the bare facts contained in the articles which make up the second part of the book are, if one can use the word, familiar to us. We have known for a long time where the cattle trucks were going, we know about the ‘showers’, we know the numbers, but reading about them as they were written, as raw news, gives us some sense of the first impact of these horrific revelations. Jacqueline’s writing is stark and unsparing, and never more so than when she is writing about the experiences of the children, those who died in the camps, who returned from the camps, who managed to survive in hiding, sometimes alone, and all the others whose childhoods were stolen by the Occupation.

‘There are no children in an occupied country, only young heroes, too young and too brave … They don’t have time to be children …’ They may be shopping for their mothers, helping their fathers hide shotguns, guiding English parachutists or Resistance workers to new hiding places. And these children were the lucky ones. For little Jewish children, Jaqueline writes, ‘the shadows were twice as dark’: trying to understand an increasingly hostile world, constantly on the look-out for danger, for themselves, for their parents, for their siblings, two year-olds diligently rehearsing their new names. The stories are harrowing: a six year-old found selflessly caring for his three year-old sister, a nine year-old narrowly rescued from suicide, children ‘saved’ by denying knowledge of their parents. Jewish Rescue Organisations did what they could, but for too many it could never be enough. They had lost homes, and parents, and love. Adolescents returning from the camps had become feral: damaged by repeated bereavement and loss, they like the others were in desperate need of affection, but they were the hardest to help. Jacqueline urged her readers not to give up on them, but to help them grow up, to make sense of their lives, to help them work at forgetting.

I have read these pages many times – I must ‘come out’ at this point as the translator of Maman, What Are We Called Now– and I have cried every time. There were moments when I was almost tempted to give up, to spare myself the pain of retelling those stories. But then I had to berate myself, to recognise the importance of not forgetting. In May 1945 Jacqueline wrote: ‘We have seen the doors open onto a world of which we knew nothing, a world of horrors, of medieval barbarism, and the doors are heavy and the hands of civilised people may not be able to close them again.’ It is a terrifying thought.