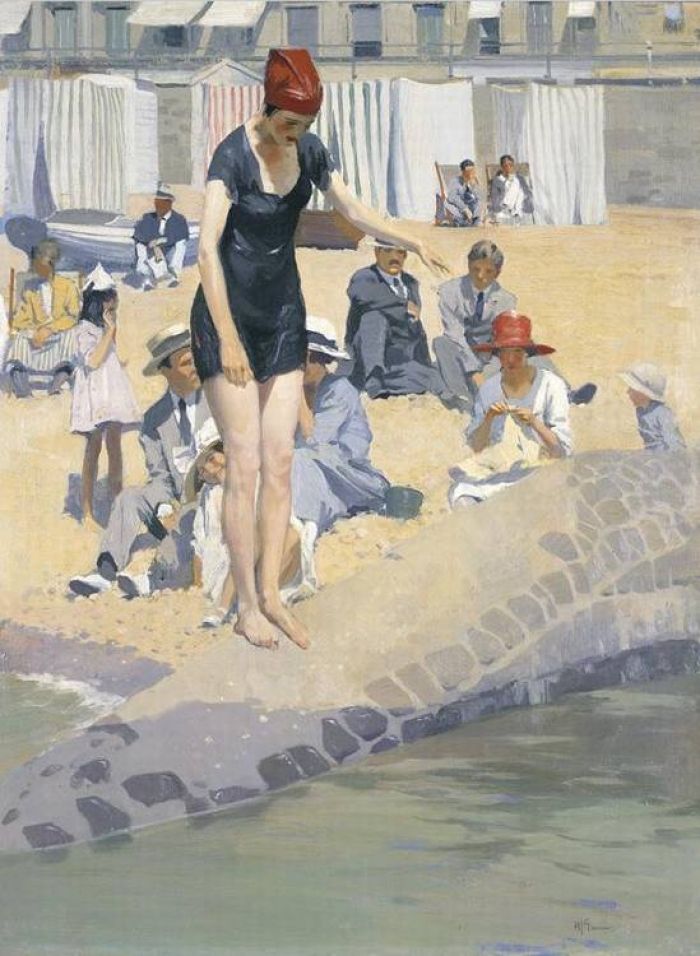

More sunbathers: July by the Sea was sold at Sotheby’s in 2003 and here is some of the extremely interesting catalogue note (which once again demonstrates that paintings are simply novels and short stories in a different format). ‘Gunn studied at Glasgow School of Art from 1909, going on to Edinburgh College of Art and later the Académie Julian in Paris. Despite his essentially Scottish training, and strong demand in London for his services as a glamorous society portraitist, it has been Gunn’s beach scenes, the majority painted on the Continent, that are most consistently sought-after by collectors. Le Havre and Dieppe was the source of inspiration for a number of beach scenes (probably Sunbathers). It seems that the present work must have been painted either at Etretat, or alternatively somewhere along the Sussex coast. Gunn enjoyed family holidays on the English ‘Riviera’ in the 1920s with his first wife Gwendoline Hillman, whom he had married in 1919, and their three daughters, Diana, Elizabeth and Pauline, before the marriage was dissolved in 1927. However, the awnings shading the windows of the buildings lying along the promenade here are much more typically French than English, as is perhaps the fact that there are a number of well-dressed men on the beach, possibly enjoying a leisurely break from work nearby. Rather than looking out to sea, as with the majority of his other beach scenes, with July by the Sea the artist turns his gaze inland, to observe in closer detail the various visitors to the beach. One charming incident is the young girl with a large beribboned hat, who looks directly at the observer from behind the knees of the central figure, appearing to laugh at the artist as he works. Great detail of observation (a man’s small moustache; a woman’s hands busy about her sewing; the girl’s right foot slightly braced as she holds her grip on the slippery groin) is unified here under the intensity of the light from the sun, which sits directly overhead and casts minimal shadow. The light bounces off the white of the striped changing tents, shirtfronts, a newspaper idly held in the distance, and the bleached sand itself. The colour palette is schematically restricted to bright primaries, relaxing into a subtle green only to suggest the coolness of the water at the diver’s feet. The picture appears to be laid out and arranged with greater consideration than the obscuring of four of the figures supplying narrative, behind the body of the standing girl, would immediately suggest. It strikes the viewer as an instantaneous impression, a holiday ‘snapshot’. However, four parallel bands describe the background in carefully graduated intervals (the buildings, the tents, the sand, the water) while within these bands pockets of action are carefully placed so as to balance each other, the whole unified by the strong vertical of the bather in her clinging Edwardian suit. The two seated on deckchairs in the right distance balance the crowd gathered towards the lower left. The left arm of the hesitant swimmer emphasises a diagonal line running through the seated figures on the beach behind her – the same diagonal that will be echoed as she makes her jump. The dark-suited man seated in the central section of the canvas watches the swimmer and anticipates her arc towards the empty lower right quarter, thus supplying a narrative anchor. Just as he waits, we wait, and in so doing can almost feel the sun.’