We hear a great deal about helicopter parents, much of it critical, far less about an alternative American movement, free-range parenting started by a New York mother, and equally, if not more controversial. In 2008 Lenore Skenazy wrote an article defending her decision to allow her nine-year old son to travel alone in the subway. The article triggered a vicious response: she was a child abuser, who should be arrested for endangering the life of her son. Skenazy countered with an astonishing statistic, ‘my son would have to stand on the street corner for upwards of 600,000 years in order to be abducted.’ A more restrained UK figure suggests that a child under 18 stands a 0.0075% risk of being abducted by a stranger (the risk of being abducted by a family member is far far higher). I can’t work out what that is in street corner years. Suffice to say that I have two six-year-old grandsons and my heart is my mouth if I leave them for half a minute on the doorstep while I go back into the house to retrieve a hat, or a purse, or a toy. Free-range-grand-parenting is not for me. But if I were a young, confident, busy mother in a community of reassuringly middle class families, in a safe middle class neighbourhood, it’s just possible that I might have allowed my small children to walk the two short blocks to school, on a path that they had trodden many times, and where they would be in sight of other children with their mothers.

When Susan Selky, a thirty-four-year-old Harvard professor of English literature, waves goodbye to little Alex, she is in no doubt about seeing him come through the door in time for cookies and milk at half-past-three. But Alex does does not come back. The six-year-old has disappeared. And just typing those words makes me feel quite hollow. A full scale search is launched. The community is alerted. Friends gather round. The media thrill to the awfulness of the story. Will the police find Alex? Will they find a body, or a living boy? But Still Missing missing is much more than a thriller.

‘By thirty-four you’re bound to have lost your Swiss Army knife, your best friend from fourth grade, your chance to be centre forward on the starting team, your hope of the Latin prize, quite a few of your illusions, and certainly, somewhere along the line, some significant love.’ Tick, tick, tick, tick. From the very first perfectly constructed paragraph, so cool, so spare, so unsentimental, and so accurate, Beth Gutcheon has the reader gripped. Still Missing is a novel about loss, which we have as she rightly surmises all experienced, though never fully shared. The word covers so many things from the trivial to the tragic. Loss is always personal. A friend’s Swiss Army knife means nothing to us, and if we are honest, their child means only a little more. Few words ring more hollow than ‘I know how you feel’.

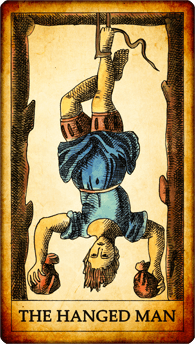

When Alex disappears, Susan is alone, but not physically: her apartment soon fills with people, police, doing their job, press and television after a good story, friends and neighbours for motives of their own. To the astonishment of the lead detective – Lieutenant Menetti had expected a meeting of ‘a couple of volunteers’ – the community gathers in force to help in the search. ‘A hundred attentive pairs of eyes were fixed on him’, a hundred people genuinely wanting to help, but wanting more than that to know whether their own children were in danger. Susan understands and is more forgiving of them than of the outer-circle, foul-weather friends, who are among the first to telephone, and whose anxious quest for news seems to have ‘a slightly lascivious quality.’ For the most part, and for a while, people do what they are able. Her busy, hippy friend, Jocelyn, ‘wielding the phone like a tailor with a pair of scissors’, takes control of the telephone tree, and much else. Everyone offers to put up posters. Some bring food, others pills; her students bring cocaine; her husband’s young mistress calls by to sympathise and, incidentally, praise her book on Willa Cather. Bossy Jocelyn suggests a therapist, ‘she does a little Jung, a little Reich, a little biofeedback …’ (Gutcheon allows a hint of dark humour to creep in at the sides). Her gay cleaner, Philippe, provides cups of coffee, and offers to read the Tarot cards.

They do their best, such as it is. But not for long. Eventually most ‘simply drop away from her, in tears, for their own reasons not being able or willing to be around pain.’

When in desperation Susan turns to a support group, which has courted her for a while, she finds them isolated by their anguish, not only from her but from each other. ‘Shared or not the horror was malignantly private.’ Wrapped each in their own grief, “Parents Remember” are barely capable of supporting themselves. Bereavement has no community.

Grief is cohesive but the glue isn’t strong. Even Alex’s father, Susan’s promiscuous ex-husband, Graham, cannot grieve in the same way, or in time with her. ‘Graham’s mourning was ferocious, like a man who walks deliberately into the heart of a storm and opens his coat to it and uncovers his head. Susan’s grieving instead seemed to be held inside her, as slow-burning hardwood holds the heat, or a well-tempered carbon knife holds an edge.’ While he wants to drive through the storm to some imagined calm on the far side, she wants to hold onto the anguish, all that remains of her son’s life. ‘Her grief, closed within her, was all the grave her son would ever have.’ I was reminded of the wonderful speech in King John, where Constance, whose son, Prince Arthur has died, is accused first of being mad then of being as fond of grief as of her child, and replies: ‘Grief fills the room up of my absent child,/Lies in his bed, walks up and down with me,/Puts on his pretty looks, repeats his words,/ Remembers me of all his gracious parts,/ Stuffs out his vacant garments with his form …

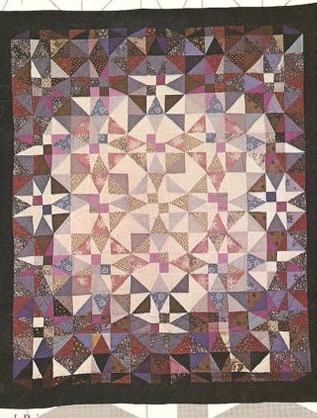

‘What she’d lost was far more than a child. Even though at the time, she’d have said there was nothing more to lose than the child. Like a deranged hobbyist who had dropped her glue and toothpick model of the Parthenon, Susan felt surrounded by scattered pieces of a world view, a view that she came to recognise as pitiful, fabulous, undefended, and indefensible. If she ever tried to reconstruct it, she would find a lintel whole, with its pillars gone, fractured chunks without supports, and the greatest pain was to recognise that after all that work, a lifetime of picky building, it was more trouble to reconstruct than it was worth.’ Beth Gutcheon’s Perfect Patchwork Primer has been on my shelves for years and I found myself picturing one of her beautiful pieces being torn apart.

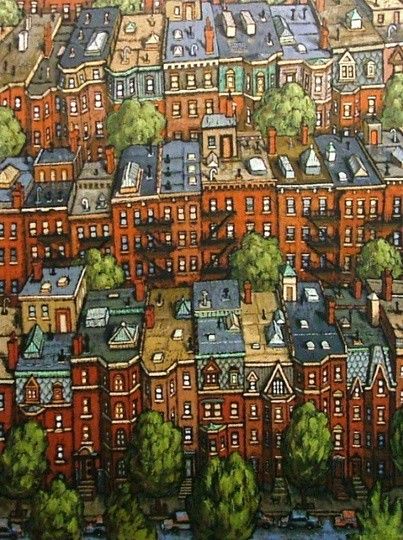

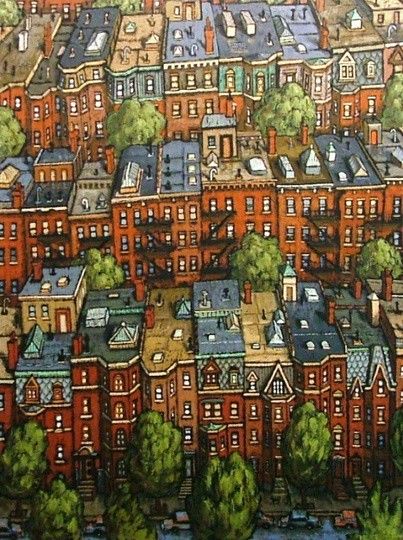

Early on she understands that whatever the outcome of the search for Alex, some of what she has lost will never be retrieved. The beguilingly unconventional middle-class up-and-coming neighbourhood of South End harbours worse secrets that a hidden stash of marijuana. Lieutenant Menetti, socially mistrustful of the excessively easy-going alternative newcomers to the as yet incompletely gentrified area of Boston in his Fourth District, is adamant that none of Susan’s family, nor any of her neighbours are beyond suspicion. And he’s right. Some of the friends turn out to have not just feet of clay but criminal records: a drug dealer, a child molester, a sex offender. She experiences ‘the relentless horror of losing her sense of the goodness of the world’. Once safe streets seem full of danger. She comes to see the world as the police see it.

A fattish, fiftyish, overstretched family man with a not entirely forbearing wife, and a seven-year-old son, Menetti is a plainspoken old-school detective, with a dry, cynical wit, utterly convincingly drawn. Gutcheon must surely have spent many hours in noisy, smoke filled police departments. The detective has seen a lot, too much, and has little time for the Selkys’ intellectual friends. When one suggests that a kidnapper would more likely have gone for a young Rockefeller he is cuttingly put down: ‘listen, people don’t usually go into kidnapping because they got tired of being nuclear physicists.’

Menetti is not an unkind man, far from it. Risking his own family harmony, he sticks with Susan to the end. With TJ, Alex’s godfather, and Margaret, Susan’s tenant, he is proof that goodness is not necessarily transitory. TJ and Margaret help unobtrusively, never seeking the limelight. He walks the dog, and, unasked, arrives to drive Susan to work on her first day back at. Margaret Mayo, ia a widow twice her age, who Susan barely knows, but it is she who seems to sense what is needed, and when, what food to provide, what words to use (very few). Gutcheon describes her as having ‘a gift for distance’. A strong woman, she doesn’t presume to share the grief, or worse appropriate it. ‘She made it clear that laughing once in a while didn’t mean giving up one’s faith, and if Susan needed to cry, she knew the difference between comforting her and demanding that she stop.’ She succeeds in preserving ‘a sense of Susan as a normal person.’ Slipping away when she’s not needed, Margaret holds a door open to the future.

Still Missing is a nail-biting thriller, perfectly constructed, no question, but I’m not sure that the term ‘page-turner’ is apt. As the weeks and then months pass, the hunt is scaled down, the ‘missing’ posters are defaced or fade, the psychics divert their ‘expertise’ to fresh mysteries, and the media, the neighbours, and finally the friends begin to lose interest, I found it increasingly hard to turn the pages, wondering if I shouldn’t open the Forum with a warning – “this book contains episodes that some readers (especially if they have six year-old children or grand-children) might find distressing.” It does, but read on. It’s a wonderful novel.