In Vere Hodgson’s own words, Few Eggs and No Oranges is ‘the diary of an ordinary commonplace Londoner during the war years’. As a diary it is honest but not revealingly introspective. It is, as the title page states, about unimportant people. And yet it draws the reader in, slowly at first, then gradually increasing its grip. The characterisation is sketchy, we learn little of the inner life of the diarist, the action does not vary much from day to day and we know what the end will be. What is it about The Diaries that holds our attention, and touches our emotions?

Vere Hodgson provides the answer in her introduction to the first published edition: ‘it records fairly accurately the hopes and fears and daily drudgery of an ordinary person during many weary springs, summers, autumns and winters’. She edited the diaries herself for publication in 1976, savagely cutting the original, which had been started to keep her cousin in Northern Rhodesia informed about the war, and later distributed to other family and friends. Impossible to know what was cut, but it seems safe to assume that she resisted the temptation to flesh out the people, that she did not take advantage of the benefit of hindsight to correct the various inaccurate predictions concerning the course of the war, and that she understood the power of repetition in building up a picture of the ‘daily drudgery’.

For the first hundred pages the published diary hardly misses a day. These entries cover the first months of the Blitz, during which London was bombed for seventy-five consecutive nights. It is true that they do not vary greatly from one day to the next. Hard to get into perhaps, but it is the record of the unchanging nightly routine that brings home the relentlessness of the bombing. Vere Hodgson writes about the casualties, and the destruction, that we know about from historians, but she tells us something else: what is was like to be woken by the air raid siren night after night, time after time, to drag oneself, and a mattress down the stairs, to sleep fitfully tight up against people who were at best acquaintances, then drag the mattress back upstairs at the ‘all clear’, only to repeat the process again an hour or so later. She tells what is was like to be tired all the time, to feel sick from exhaustion and ‘speechless with fatigue’ to make one’s way to work, to go on doing this day after day.

Almost imperceptibly the mood changes: by August the siren which in June had sounded so alarming, has been nicknamed Wailing Winny. By October she can write of a night which is ‘very gunny’, another which is ‘very blitzy’.

London Transport Museum

Vere, like others, is adapting to the war. In January 1941 a plane flies low as she lunches in a café, ‘I never thought I should get used to having my lunch on a battlefield’. By May a routine is well established at the Sanctuary: in case of an air raid, get everyone downstairs, turn off the gas and fill the bath (to put out stray fires). ‘It is amazing … how well our nerves keep on the whole. If we are bombed then they go a bit; but if we survive the night, we come up bright and smiling the next morning, very keen to exchange notes on the adventures of the night’. If the aim of the Blitz had been to break the spirit of the British people, it was not going to be allowed to succeed.

Vere was 39 at the start of the war, unmarried, a graduate of Birmingham university, an ex-teacher, working for The Greater World Association, a welfare charity in Notting Hill Gate, living first in a bedsitter and then a flat close to her work. If she has a private life, we learn nothing of it. From time to time she entertains the dashing Barishnikov, who spends his points at Fortnum and Mason, or the German exile Dr Rémy, whose family is in Frankfurt, or Retsi, the Swiss accountant, for tea, and on one occasion she is given two tickets for the Albert Hall. The diary does not reveal to whom she gave the second ticket.

We know that she reads widely, listens regularly to the News, French and English and to the Brains Trust, takes the Daily Telegraph during the week and the Observer on Sunday, and is a keen cinema goer (brave given the number of bombs that fell on cinemas). Her admiration for Churchill knows no bounds, De Gaulle runs a close second. For the rest of the French nation she has little time. She admires the Russians. Unexpectedly for one so spirited, she complains frequently about her health, but is fit enough to jump from a 10ft wall during fire fighting practice, and tough enough to volunteer to be the ‘body’ dragged down the stairs during the same practice. She is an energetic walker, taking regular Sunday walks, sometimes in pouring rain, through the West End and the City to look at bomb damage. Local damage is inspected on the instant: ‘I was told that bombs had fallen again in St Charles’ Square, so I took a bus there’, ‘… heard there had been a landmine last night in St Helen’s Gardens. Immediately took a bus.’

She is quite shameless about what might seem to us a rather ghoulish curiosity, so shameless that I think we can assume that bombsite viewing was not a minority interest. The picture of Miss Moyes being pushed in a wobbly wheel chair on ‘a tour of the bombs she had not seen’ is, almost, funny, the brief description so vivid: the sides of the chair coming unscrewed with the vibration, Miss M having to dismount every time they crossed the road (in spite of everything, ‘she enjoyed the outing’). When Vere hears that The Rowley Galleries in Church Street have been burnt out, she runs to see it, ‘remains of beautiful furniture and pictures all in the street’. The bizarre aftermath of bombing never loses its fascination for her. As late as July 1944 she records ‘A spot of excitement. No sooner had I reached my little flat than a Doodle came close in our direction. Roar grew louder … We took breath – heard the engine stop – and then the explosion.’ Hearing that the bomb had fallen in nearby Earl’s Court Road, devastating a crowded restaurant, barely pausing for lunch, she’s off to survey the damage. There is an urgency in her telling, such that we can almost hear her voice, giving us ‘the latest’.

Vere Hodgson notes down not what is, or might be, of historical importance, although those events are included, but what excites her, a bombsite, an extra ration of cheese, a trip to the Zoo with a party of children, the discovery of a hoard of Renaissance treasures from the Uffizi hidden behind mattresses in a villa outside Florence, de Gaulle’s extraordinary courage under fire as he walked the length of the nave of Notre Dame while German snipers took aim from the galleries.

As the diaries unfold her darting style become familiar and strangely endearing. The big picture and the small sit side by side. In the bitter winter of 1942 she buys a spare hot water bottle, ‘They say there will be no more for years; so I am keeping one in reserve until we get Malaya back…’. The entry for 8th September 1942 records the loss of 80,000 men in the desert and in the next line, ‘Plenty of blackberries – so we wallow in fruit’. In March 1943, from buying curtain material in Liberty’s, she moves seamlessly to the horribly wounded from Dunkirk, and in the written equivalent of the same breath, to the scarcity of biscuits, and her delight at finding soused herrings at 8d each – ‘no fish for months’.

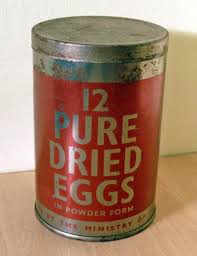

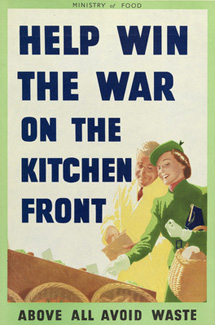

In September 1940 she had written to Lucy, ‘food is the least of our worries’. Not for long. By November she is thankful for two eggs, the following February there are ‘No oranges at all, at all’, and cheese is unobtainable. In May she admits to disregarding the news, which ‘shows no sign of improvement, concentrating instead ‘on procuring food to eat.’ Food and the price of food becomes a leitmotif of the diaries, despondency about shortages, surprise and delight at unexpected availability. Prunes, spurned before the war, acquire rarity value and are eaten with pleasure. Macaroni is unavailable but figs make a surprise appearance. Stays in the countryside provide an opportunity to gorge on plums and cherries and fresh vegetables. The Hodgson family manage a goose for Christmas lunch in 1940, and again in 1941, but by 1942 ‘no turkey, no fowl, no rabbit, only the usual joint’ – Auntie Nell in London had acquired a hare, which ‘required a special license’.

Christmas in Birmingham and the Sanctuary Christmas Fair are two fixed points in these years. The flowering of the cherry in the street, the laburnum and the lime in the park mark the turning of the seasons and lift the spirits. But little could be taken for granted, and certainly not waking up alive, unhurt and in one’s own bed. The cityscape changed almost from day to day during the bombing, good news was followed by bad, invasions do not go according to plan, but nor do train journeys. The Diaries remind us that adversity can take many forms. The lack of a colander is preoccupying, finding a small double saucepan or a rolling pin at a reasonable price makes for a good day. An onion from the greengrocer, when all had been ‘booked’, is ‘a victory indeed’. The gift of sheets is worth more than rubies, when on the old ones even the patches had been patched, and new ones are unobtainable. Feast and famine were as unpredictable as the course of the war. In the final months, during the ‘little blitz’, there were fewer shortages, more food, more coal, more books in the library: death and departures had made a dent in London’s population, there was more to go round.

By September 1944 the end is in sight. The sirens have fallen silent. Soon there will no more bombs, the black-out will end, it will be possible to move around at night without a torch. The nights on the stairs have come to an end. A hint of regret creeps in. ‘We have all got friendly in my Flat residence due to the Fly Bombs. The Old Dears have lost their pernickety ways, and as we sat on the stairs, not knowing whether the bomb was going to drop on us, we became very much a band of brothers.’ Mollie Panter-Downes in Good Evening Mrs Craven put almost the same words into the lonely spinster’s mouth, ‘Those nights, terrible as they had been, certainly had had their compensations. It seemed to Miss Birch, looking back, that the inhabitants of Floor K had been one jolly happy family…’. There will be eggs and oranges in the shops once again, but something will have been lost.

Questions

Most of those who thought Few Eggs ‘hard to get into’ have returned to it and found it a compelling read. What is it that make one want to keep turning the pages?

“Wartime Spirit”- what does it mean?

There are so many questions that one would like to have asked of Vere Hodgson of wartime life. Is it possible to imagine how we might have behaved?

11 replies on “Persephone Book No 9: Few Eggs and No Oranges by Vere Hodgson”

I love this book. I borrowed a copy with the 70s yellow and cream cover from the library many times and even considered stealing it because I was worried it was so old and battered it would be retired from circulation. Then I found your lovely online shop through Jane Brocket and was so happy to find you had my dear book waiting for me. I bought it straight away and could hardly wait for it to fly half way around the world to me in Tasmania. Just love this book, the matter of factness of it, the dailiness of it, her wonderful jam making aunt, the reality that life had to go around and through all the destruction and worry of war. Thank you.

I have all the Persephone books and have read most of them, but this volume of Diaries is one of my favourites. I think that it is the immediacy and the lack of art in this record that make it so vivid and memorable. While I realise it was edited and sorted for printing, it does retain the air and tone of being written in the moment, not justified and clarified for publication. Comments like “We are all speechless with fatigue. I shall sleep if bombs fall round my bed” made in October 1940 is so realistic. Anyone who has not slept properly for a while will know how this feels! I have read quite a few diaries of the war years, but often they are too brief to appreciate the personality of the writer as well as the events that they describe. No such problem here. It is a lovely, long account of honest detail and emotions from a woman doing her bit. I know that one criticism of ‘oral history’ is that it tends to tidy up and sanitise memory, so it is a particular bonus of this Persephone edition that it is easy to read yet faithful to the original. I just love big books!

In talking to my 93 old friend (see questions) I was struck by the way in which her memories of the war echoed Vere Hodgson’s. “I don’t remember being frightened.’ she said, ‘what I remember above all is being blindingly tired’.

This is one of the first Persephone books I read, so tonight I’m going to begin a reread – something I rarely do. Also planning a trip to the Imperial War Museum on Friday so this month’s choice is rather timely for me.

I read this and ‘An Interrupted Life’ not long after each other – I actually can’t remember which one I read first, now. And although Etty Hillesum’s account is far more tragic, and dramatic (as well as being more illuminating of the author personally), I was struck by the similarities in the ‘at home’ experiences of war. Reading the blog comments about ‘Few Eggs’ surprises me as I don’t recall finding Vere Hodgson’s accounts boring or dull or samey at all; I found it compelling from the start. I think I need a re-read as well Emma!

I also remember being very excited to see the Jacqmar scarf used in the endpapers as part of the ‘war at home’ display at the Imperial War Museum!

I just finished reading Few Eggs this past week, and I was completely fascinated by it. As you say, Vere Hodgson inserts very little of her own thoughts and feelings into the diary (aside from her obvious hero-worship of Churchill), but she’s so unfailingly honest in her observations of the war and its impact. The following is a paragraph that really stood out for me as i read:

[Sunday 11th May 1941] (p. 171) “Just heard the terrible news that Westminster Hall was hit last night. Also the Abbey and the Houses of Parliament. They saved the roof to a large extent. In the Abbey it was the Lantern. At first they thought Big Ben had crashed! One cannot comment on such things. I feel we must have sinned grievously as a nation to have such sacrifices demanded of us. Indeed future generations will say we have not taken care of what was handed down to us. We should have been more careful to defend it. We must pay the price now; but it is terrible to think of the wasted years, when, sunk in enjoyment, we did not realize that the days of all we looked on s precious were numbered—that our rulers and ourselves had lost their way in a mist of false high thinking, and common sense had gone.â€

Although I liked Vere as a person, I found that there were some contradictions to her as well; I thought it was touchingly sweet how preoccupied she was with fruit, or the lack thereof. But as Vere’s diary shows, Londoners in fact were better off than many during the war–even during the days of the Blitz. I thought this was a really thought-provoking book.

I agree with joulesbarham that it’s the lack of art which makes this such compelling reading. When most of one’s wartime experience comes from the contructed evidence of films, novels,even documentaries, it’s the memories of those who lived through it which are more immediate. And the immediacy of these writings brings one up short as one reads. My initial thoughts were how tedious it was to keep reading the same night-time events of the Blitz. And then I had to remind myself that this was not written for effect. This was written as events took place. This was how they lived.

Simililarly, Vere’s language is artless, too. She describes how lovely it is to be ‘bowling along the country lanes’ during a welcome break in the countryside. And that’s how we express ourselves when we’re not contructing art. We speak in cliches – people are always ‘rushed into hospital’, tanks are always seen ‘rolling in’ to put down rebellions, and we always go ‘bowling along the country lanes’ on our bicycles when we’re happy. And yet, she can still be very poetic – when she writes of the ‘heavens . . . . sobbing over the sorrows of man’ she reminds me of Edith Sitwell’s ‘Still Falls the Rain’, and her desciptions of the ‘lovely moon and stars’ made all the dearer after a night of anxiety during a raid are simple but beautiful.

The work is also interesting because she makes unwitting comments about the prevaililng sexist and racist attitudes of the day. She can be both realistic, in admitting that the ‘successes of the R.A.F. are so joy-bringing that we are in danger of forgetting the darker side of the picture’ and unrealistic, describing a raid on Wimbledon at tea-time as ‘just sheer wickedness’. I guess that’s what war does to us in confusing our judgements – what we do is heroic but when the enemy does the same thing it’s anything but. We are ‘Our Boys’, but they are ‘The Brutes’ or ‘The Beasts’. She does also make me wish I’d seen Coventry before the war. It sounds rather fairytale – like the snatches of Nuremburg in ‘Triumph of the Will’.

I think that Vere Hodgson does unintentionally what many authors strive most intentionally to achieve: she holds up the mirror to ourselves. In describing how her mother and sister were managing in Birmingham, she says that it ‘is just a typical experience of hundreds of simple people, who never thought they would have to face anything like it. So I record it.’ And we have to be grateful not only that she did, but also that she ‘did pretty well’.

Thanks for linking to my response to the diary: it was definitely a memorable Persephone experience and the images you’ve chosen for your page are perfect for Vere Hodgon’s book. Another Persephone that I read in the same month was Etty Hillesum’s diary, which made the ideal reading companion for me. It felt like such an intimate glimpse into the diarist’s life.

Thank you for your kind comments about the images. I lived very close to Ladbroke Road as a young mother, and often walked past the police station on the corner. Forty years on the air raid siren, which nightly woke Vere Hodgson, was still on the roof. We often wondered if it was caution, nostalgia or inertia which kept it there. It has gone now.

Few Eggs also fills in some of the background to last month’s book, Mollie Panter-Downes Wartime Stories. Mollie herself spent much of the week in London, and knew at first hand the deprivations, and the destruction that confronted Londoners daily, and understood too the warmth and camaraderie generated by the shared danger. She knew also what it was that the evacuees and their mothers were escaping from.

My elderly friend, whose family house in Landsdowne Road (in which she still lives), close to The Sanctuary, was, incidentally, the ‘house on the corner’ which was ‘still burning’ when Vere walks to Clarendon Cross, was fearless until the birth of her first child. ‘Then, I had to leave’, she said.

I found this book SO hard going it took me several years to finish. At least it was able to be dipped into and out of and I felt quite a sense of achievement when I did finally make it to the end.

But it is a wonderful piece of social history and it certainly leaves you with an atmosphere of the war I have not found from reading other sources.

I was rather ambivalent about Vere – not sure she is someone I would have wanted to get to know.

This was the first Persephone I read, and I loved it – consumed it with relish, as though it were one of the missing oranges…

I think, even though she did edit it, it has stuck with me more than many other accounts of the war – it wasnt written or rewritten for anyone other than her family & friends, and it is about normal life. So often one reads about the war & great heroics, but there were many people for whom the fight to get food & sleep was their war – and perhaps one more likely to have been how more people “like me” would have been – .

It is impossible, I feel, for anyone who was not there to know what it was like, so I cant bring myself to judge Vere as a person, and that she left herself open as it is published is a different sort of bravery. I live near where huge bushfires destroyed towns and lives outside Melbourne, and we got a large number of tourists coming to look, so I would presume, given human nature, many people would have toured the bomb sites. There is, however, the other side – local businesses here that didnt burn needed the custom, and the tourist gave that to them, and maybe that could also happen – to have people come & stare at your bomb ruins may have made you feel a bit better & you could tell them your story & be comforted and famous through that.